Credit: Leiden University College, The Hague, Netherlands (2024)

Educational Stories: Exploring the Social Determinants of Health in the Netherlands, Myanmar, and Gaza (v1)

The Social Determinants of Health (SDH) are the non-medical conditions in life that shape health and well-being. Such conditions are determined by where people are born, grow up, work, live and age, which are also affected by the ways societies are built, such as economic systems and/or political systems. SDH is taught at Leiden University College (LUC), The Hague as a course in virtual collaboration with students from Virtual Federal University (VFU) in Myanmar and Gaza.

In this HAB blog piece, LUC Assistant Professor of Global Public Health Jyothi Thrivikraman and course students share how collective storytelling as an educational strategy can play a role in building shared understandings across varying contexts.

About SDH

SDH education offers valuable insights and skills for those working in health-related professions such as doctors, caregivers, and public health officers. Three core questions guided the SDH course:

- How do social conditions get embodied?

- What are the causal mechanisms? And what theories support these mechanisms?

- How is data collected to understand this embodiment?

As students from wildly different contexts would be working together for the first time, it was important that they had some familiarity with each other beforehand. Ahead of their first meeting, the LUC and VFU students were introduced to each other's contexts through a series of articles and videos which delved into the historical and sociocultural background through which they would begin to work towards the core questions.

Students were divided into groups working on one relevant topical area: economic stability, education, social/community context, and physical environment. Each area was broad enough for students to narrow down their focal areas. Students conducted a literature review, interviewed either each other or those around them in their respective regions related to the topics.

Stories were co-constructed enabling shared understandings to emerge. Rather than a call for direct answers or solutions, the course emphasized a focus on personal experience, with the topics acting more as guidelines for conversation. For the students, it was a self-reflection of what they did everyday, these conversations connecting them with those in their immediate vicinity, but also those of their groupmates.

When asked about their experiences, they would mention how these connections made the reality of their peers' situations "more concrete," with some students saying,

"Notwithstanding the constant problems of connection and the difficulties of the language, without their help and introspective insights on our topics, the results [of our study] would have been very different.

"From lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic to armed conflict, every story we had the privilege of listening to is unique, and we can only share a fraction of what these people experienced."

"I didn't realize how much work it took to be a Palestinian."

We present a few of these stories and reflections below, highlighting resilience, love and life even in the midst of forces that wish to destroy.

Group 1: Economic Stability

Written by Haytham Abuzaid, Brynn Cochran, Jasper Jansen, Dolça Collado, Lama Mouharb, Hesham Al Amassi, Khant Lin Paing, Soe Yu Ya Aung, Khin Myat Mon

Pregnancy is often conceived as a time of joy and care, but for many women in conflict zones, it is marked by fear, instability, and serious risks. . Our project aimed to answer the following question:

How do pregnant women access healthcare services in conflict areas?

In Myanmar, economic instability is made worse by political conflict. Interviews with women in the region revealed how financial struggles prevent them from accessing even basic prenatal care. One interviewee, a former preschool teacher who is currently pregnant explained that despite the need for medical attention, many pregnant women cannot afford it. Economic instability in Gaza has also worsened due to the ongoing war, leaving pregnant women without essential vitamins, medicine, and even food. "There are no vitamins, no treatments, no food. Even household chores are exhausting without electricity and gas," one woman explained. Pregnant women in Gaza also face additional challenges due to destroyed roads and bombed hospitals. The economic instability caused by war makes medical care inaccessible for the most vulnerable, leading to high maternal and infant mortality rates. Without financial stability, healthcare resources, and safe access to hospitals, pregnancy becomes life-threatening.

Story 1: Gruelling Experience of a Pregnant Woman in a Conflict-Affected Area in Myanmar

Before the war, she was a schoolteacher. Now, her days start before dawn. The hospital is far from her refugee camp, and with only a month until her due date, motorbike rides are no longer safe. Renting a car is costly, but necessary.

Last night, she barely slept. Airstrikes shook the ground. The fear is constant, but there’s no time to rest. She must reach the hospital before the crowds. Though in her third trimester, she still doesn’t know her baby’s gender. She worries, have the bumpy roads harmed her unborn child?

The hospital opens just once a month. If she’s late, she might miss her check-up. She double-checks her wallet. Inflation has made vitamins and basic care nearly unaffordable. To save money, she packs her own food. Constantly wondering whether that is enough to live or at least, survive. Though some support exists, it’s never enough. Every decision is about survival, for her and her baby.

“It’s okay,” she tells herself. “Only one month left… Then it will be okay. Won’t it? Will I be okay? Am I really okay?”

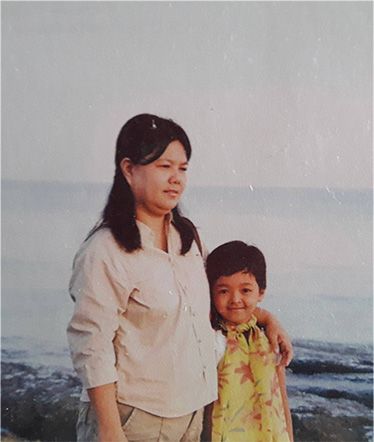

A Burmese mother with her son.

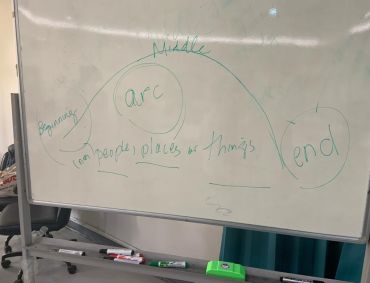

SDH Group 2 (2025)

Story 2: A Mother’s Journey - Surviving Pregnancy in Gaza’s Shadows of War

My name is Amal, though some days I forget it. The war has a way of eroding identity, reducing us to survival. I am 28 years old, pregnant with my first child, and I live—if you can call it living—in what remains of Central Gaza.

It began with displacement. When the bombs fell on our neighborhood, we fled on foot, clutching what little we could carry. My husband held my hand tightly as we joined the river of bodies moving south, my swollen belly a cruel reminder of timing. The 23-kilometer walk left me breathless, my legs trembling. At one point, I collapsed, convinced the life inside me had faded. But somehow, my baby clung on.

Now, in a tent in Khan Younis, each day is a battle. There is no electricity, no gas. Simple chores—washing clothes, boiling water—exhaust me. My hands ache from scrubbing, but worse is the gnawing hunger. Food is scarce: bread when we’re lucky, canned beans that taste of metal. No vitamins, no prenatal supplements. My bones protrude, and my baby kicks weakly, as if already tired of this world.

The hospital is far away, and reaching it is its own struggle. Roads are rubble, transportation is limited, and checkpoints choke every path. I leave at dawn, hoping to catch a ride, and usually arrive at Al-Awda Hospital around noon. The journey is long and draining, but I have no choice. Yesterday, I was told my baby weighs only 2.2 kilograms—malnutrition, they said. The medical staff was kind; they explained my options and gave me a chance to deliver naturally. If not, a C-section will be arranged because the baby is too small.

They say resilience is our strength, but what does that mean when resilience is all we have? My family tries to help. My mother massages my swollen feet; my sister whispers stories of Gaza before the war, where hospitals had lights and incubators. But their words feel distant, like echoes. My husband is gone most days, scavenging for firewood. When he returns, his eyes are hollow.

The worst is the silence between bombings. In those moments, I feel the weight of this child—a life I cannot protect. I think of the mothers in the north, trapped under rubble. I think of the ones who gave birth in foxholes, their babies’ first cries drowned by drones.

They ask what needs to change. Restore the clinics. Bring back the doctors. Let us plant gardens where missiles now fall. But first, stop the war. Let my child know a sky without smoke, a night without sirens. Let them taste an orange, sweet and whole, not rationed by siege. I am due any day now. I pray this baby waits until the shelling pauses. I pray they survive.

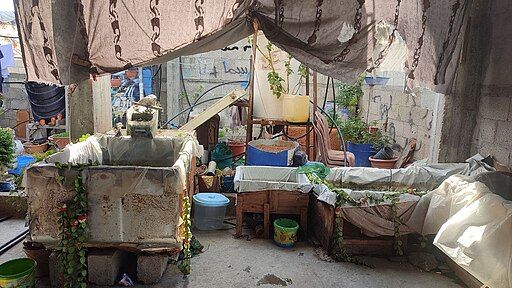

Foreign and Commonwealth Office via Wikimedia Commons, OGL v1.0OGL v1.0 (2008)

Group 2: Education

Written by Paulis Baskevics, Jonne Huiveneers, Rawan Nawas, Mohammed Ramlawi, May SDH-373, Shari Thiem, and Saskia Türk

For the eight-week project of our Social Determinants of Health class, we were put into a group consisting of students from The Netherlands, Germany, Latvia, Gaza, and Myanmar. In an effort to narrow down our research aim, we engaged in conversations to find out our common interests. As an interdisciplinary group of students, we saw the potential of combining medical and social science backgrounds to gain deeper insight into the perinatal education our mothers experienced. We examined the current literature on perinatal education, decided on a preliminary research question, and wrote a literature review evaluating all the sources. From here, we decided that the best people to interview would be our own mothers, particularly their experiences of giving birth to us.

To present our stories in a way that engages the audience beyond factual information, we chose to turn our interview findings into a dynamic conversation between a midwife and a newly pregnant woman. During their extensive chat on a park bench, the midwife tells anecdotes from different women she encountered during their pregnancy journey. While they lived through distinct situations, facing unexpected challenges, all mothers ended up just fine. In comforting the pregnant women, the story aims at conveying the emotions the interviews arose in us, which connected us despite geographic distances. In summary, the story we wrote emphasizes the emotional aspects of pregnancy, which we found to be undervalued in current research compared to physical well-being.

Story 3: Maternal Healthcare Education in The Hague

On a cloudy day in The Hague, a young woman walked through Haagse Bos. In her hands, she carried a bundle of papers that rustled as she sat down on a bench. With a deep exhale, she put the pamphlets from the gynecologist down next to her. This had been a tough day. She opened the first one and started reading:

“The etymological meaning of the word ‘midwife’ comes from Old English, meaning ‘with-woman.’”

Great, she thought, how is this information supposed to help me with my pregnancy? She felt the tears of overwhelm building up. A gust of wind blew her hair and the pamphlets flew across the ground while the first tear started rolling down her cheek. She bent down to pick up the pamphlets, but was startled by another woman picking them up.

“This looks like a lot of information,” the elderly woman said.

“Yes….I just wish someone could tell me what I actually need to know. All of this is so confusing,” the young woman replied.

“What do you wanna know?” the old woman inquired.

“I just found out I’m pregnant," the young woman said. "I don’t know what to do? How do I prepare? Do I have to take medication?”

“Well it just so happens that I’m a midwife, and if you’d like I can tell you the stories of the other mothers I have helped.”

“That would be amazing.”

The young woman looked up with anticipation and met the old woman's eyes. With this invitation, the midwife sat down next to her.

“Tell me child, do you have a strong community around you? From my experience that is the most important factor to make pregnant people feel safe and supported. And with that I do not necessarily mean your actual family. Friends and colleagues can be just as supportive. If you tell them about your pregnancy, I am sure they will share their experiences with you, which can help you prepare but also provide you with emotional support."

The elderly midwife takes a deep breath and rocks back, recalling years of experience in a single moment.

"A mother I helped in Palestine found her husband’s medical background extremely helpful because she felt more secure knowing he understood what to expect. Most other mothers also relied on their partners, which could be helpful to you. However, it’s also okay if you don’t want to listen to their stories all the time because it can be quite overwhelming.

"A mother from Latvia was scared after hearing stories from her mother and how she was separated from her baby after birth. What I want you to know is that emotional support from the ones close to you, can help to reduce stress and comfort you.

"It’s okay to be scared. Childbirth is a physically and emotionally intense experience for all mothers. However, you live in a country with a good healthcare system and a lot of intervention options. I once met a mother from Palestine who could not get medications so she struggled through pain and fear, while mothers from countries that offered such relief did not feel the need to take them at all. Still, some deliveries do not go as planned. A mother that I helped from Myanmar was sad about having an emergency C-section because she wanted a natural birth, but afterwards she told me that the excitement and pleasure of seeing her baby was bigger.”

The young woman's gaze went downward, and in a low voice, uttered worryingly.

“I am afraid that my body is going to change,”

The midwife placed a hand on the expectant mother's shoulder, looking at her reassuringly.

“Actually, I met a mother that learned to trust in her body and appreciate its capability even more. So trust the process and it will be fine.”

The young woman took a deep breath. This time it was full of hope and excitement. She thanked the old midwife and told her how excited she now felt to become a mother. They hugged goodbye, thankful for the fortune to have met each other on this difficult day.

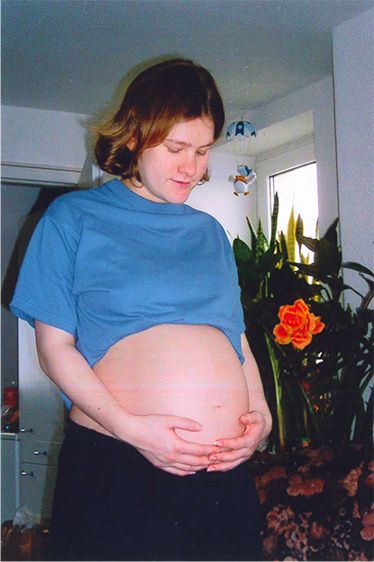

A young expectant mother from The Hague, Netherlands.

SDH Group 2 (2025)

Group 3: Social and Community Context

Written by Valentina Nieto, Martino Tonci, SDH-04, Villarni Ferreira Ramos, SDH-34, and Lama

We chose to focus on religion as it is a very ancient way of bringing people together, and we wanted to see how its impact evolved over thousands of years. The will to concentrate on unstable political contexts was to highlight how religion helps in times of extreme mental suffering. Starting the research, we saw that all religious impacts converged on four major functions, thus, we decided to talk about religion as a single entity.

Our observation of how religion affected mental health was divided into four sections:

- Religious faith causing hope and belief in a greater future

- Religious indications as a source of orientation for believers

- Religion's role in creating security and protection from mental distress

- Religion as a source for comfort

From the four sections, we found contrasting results on how religion affects mental health in unstable political contexts, the interviews gave us a more internal perspective on how religious mechanisms work. The results we found in the literature showed how religious faith was generally a factor that stimulated hope and was a cause of stronger coping mechanisms. Some scholars underlined how the guidelines provided by religious faith provoked behaviour constraint and feelings of self-efficacy, directing people toward a “right path.” The communities formed around these religions indicated that they functioned as a shield for those who are a part of them. Another scholar pointed out how religious guidelines are limited and not generalizable and could lead to isolation.

The interviews gave more nuanced results; some respondents supported the scholar's theories, while other interviewees, however, pointed out that they did not see their situations as something to hope for. The interviewees mainly identified religion as a guide, having better emotional security through participation in the religious community, but one explained how it also exacerbated social conflicts in their region.

Story 4: Religion and Mental Health

I am religion, a powerful force that has shaped civilizations and comforted hearts. I reduce anxiety, as faith offers people “something” to hold on to. This “something” might be a divine presence, an eternal truth or a purpose beyond the chaos of life. Through prayer and meditation, I offer peace of mind, a refuge from uncertainty. I unite people, granting them a sense of belonging, a community that embraces differences and assures acceptance. However, I am not without contradiction. Though I preach morality, I fail to deter crime. Despite my commandments and sacred laws, crime rates rise, and darkness persists in this world. Even though I am a paradox, I still comfort the powerless against human nature’s shadows. I am questioned, debated, worshiped, and doubted, but I remain, ever present, ever shaping, ever offering comfort to those who seek it, even as I struggle to change the world into a more just one as I wish I could.

When the world feels unpredictable, I remind people of what lasts beyond any political crisis: hope, morality, and the belief in something greater than themselves. While I may have been used to justify violence, more often I am used as a source of hope. When citizens lose faith in their leaders, they can turn to me for hope in a future, because I am not tied to any government… I am a universal figure across all cultures and throughout history, whether people believe in god, nature, or higher ideals, I can shape communities and offer hope beyond individual beliefs, often being associated as “the salvation”.

Some people say that I offer guidance to people who believe in me. In my many forms, I always provide indications that my believers can follow. My guidelines have oriented my believers away from terrible outcomes. My teachings can make people follow the right path and feel like they are doing the right thing. Alas, I have not received many updates, and some of my directions have been unchanged for thousands of years. Nowadays, therefore, my directives can be confusing and lead to disorientation rather than to the right path.

Group 4: Physical Environment

Written by Ananya Chawla, Ali Radi, Noor van Jaarsveld, Orsanne Dehem, Toe Lin Aung

Our physical environment shapes us in ways we often take for granted. Access to green spaces is not guaranteed for everyone. However, they are essential to especially family well-being. We decided to explore the question:

How does the accessibility of green spaces impact the well-being of families in the Netherlands, Egypt, and Myanmar?

We conducted interviews with families from three different countries, each with unique relationships to green spaces.

In the Netherlands, we interviewed a family living near Vondelpark, where green space is intertwined into the urban landscape. The father, Sandeep, originally from Mumbai, described the park as a sanctuary. His wife, Japke, valued its role in her daily commute, while their daughter, Mallika, had grown to appreciate it as a place for exercise and reflection. Their story illustrated how proximity to green spaces fosters a routine of outdoor activity and social interaction, benefiting mental health and family cohesion.

In Myanmar, the conversations took place in a rural setting, where nature is abundant, but urban development threatens traditional ways of life. A mother and daughter spoke of the vast farmland near their home, where fresh air and open spaces contribute to well-being. The daughter, now grown, reflected on the contrast between rural and urban experiences, noting that city dwellers struggle to find the same connection with nature. She saw parks as crucial to maintaining mental balance, reducing stress, and fostering social interaction.

Their perspective highlighted the importance of preserving natural spaces as Myanmar urbanizes. In Egypt, where access to green spaces is highly limited—especially for lower-income communities. A mother and her young son described the struggles of living in a place where green spaces are often privatized, unsafe, or too distant to access regularly. Safety concerns and financial barriers prevent many Egyptian families from enjoying the benefits of nature, making it clear that urban planning and public investment play a significant role in ensuring equal access.

We decided to shape our results section through storytelling from the perspective of a park or fitting green space for each country, allowing the stories to be told creatively, and conveying meaningful information. Though vast differences in usage, safety, access, and availability exist between the three different countries, green spaces are essential for the well-being of families in each place. Therefore, the accessibility of green spaces is an important issue and should play a larger role on the political or urban planning agenda. The research revealed that accessibility goes beyond physical presence but also includes factors like safety, affordability, and urban planning. Without careful consideration, green spaces risk becoming a privilege rather than a right. We need to ensure that every family, regardless of location or socioeconomic status, can enjoy the proven benefits of green spaces. Because in the end, our well-being is deeply rooted in the environment around us.

Story 5: Aunglan, Myanmar

I am a grassy space near the Aunglan Township in the Magway Region of Myanmar. It is summer and people are waiting for the Thingyan water festival. It is too hot to survive in Myanmar with the frequent electric outages. Some leaves have begun to fall and change to a yellow colour. A 45 year old farmer is walking over me. She spent most of her life in farming allowing her to breathe fresh air. She says to herself, “the farm provided us with fresh vegetables, which contributed to a healthy lifestyle.”

Her 23 year old daughter is with her. Both mother and daughter are talking freely about me. The daughter says “A river flows near my village, and beyond it lies a forest, offering ample space for recreation and relaxation.” Yes, the river is beside me. The mother says: “On days when I don’t spend time in nature, I feel locked in.” This is the kind of support that she gets from me. I am glad to hear she feels these benefits.

I can provide space for people to play and relax. But in cities, people struggle to find me because of overpopulation and infrastructure expansion. The woman said “cities are often overcrowded and polluted, which can have a negative impact on health”. The daughter whispered to her mother, “I believe that increasing the number of parks and gardens would improve access to green spaces, especially for those living in urban areas.” I am not just a location. I can strengthen social bonding between people. Myanmar people cannot use aircon and fans to get relief from high temperatures. So, people come to me to take a break. They talk, read and laugh for a while. In this way, I become pivotal for social bonding.

Pine trees and rice paddies in Myanmar.

Vyacheslav Argenberg via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0 (2008)

Story 6: Tanta, Egypt

I am a green space in a rural village near Tanta, Egypt. I overheard one mother describe living in an agricultural environment with limited access to clean water and electricity. She works physically demanding jobs both on farms and at home. She misses going to green spaces to just relax. In the past, green spaces were abundant, and children played freely in my fields. However, urban expansion and the use of pesticides have reduced these areas. Accessing green spaces is difficult due to safety concerns and lack of maintenance; I have not been cleaned in some time. Women feel unsafe in my borders and the safer spaces are all privately owned or unclean.

Without access to green spaces, I can see children playing in the streets, exposing themselves to dangers like traffic and pollution. My green grass turns yellow whenever I see children playing in the streets, especially when I am so close-by and empty.

The mother is remembering her childhood visits to my gardens during family gatherings bringing peace and social connection. She wishes for more well-designed, nearby parks with shaded areas and safe playgrounds. She longs for a place to take her children to run around.

I once fostered community bonding, especially among women and children. My decline has led to social isolation, making shared gardens and accessible parks a potential solution for rebuilding community ties.

A couple sitting in Al-Azhar Park, a significant public green space in Cairo, Egypt, developed in 2005 on a former landfill site.

Synaps Commons via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0 (2011)

Group 5: Economic Stability

Written by Jana Camek (Based on work with Deema Abu Sultan, Hay Mi Jue, May Thet Sun, Nay Wunn Myat, Kioni Surborg, Jay Honkanen)

Access to food is a fundamental human right that is frequently compromised in conflict areas. The repercussions extend beyond mere hunger, significantly impacting both physical and mental health. Our research aimed to highlight the nuances of human experiences in Gaza and Myanmar through the method of storytelling. Interviews were conducted by the students in Palestine and Myanmar to gain firsthand perspectives from individuals in conflict zones. In relation to food access interviewees were asked what their biggest challenges were, how their lives and mindsets have changed, the role of communities, and more. Responses highlighted the deeply rooted barriers to food security, influenced by both financial instability and logistical constraints.

"What are the biggest challenges you face in getting enough nutritious food?"

Interviewee from Myanmar:

အမှန်တိုင်းပြောရမယ်ဆိုရင်တော့ ငွေကြေး နဲ့ လမ်းခရီးကတော့ စားသောက်ဖူလုံရေးမှာ အကြီးမားဆုံးစိန်ခေါ်မှူပေါ့နော်။ ဥပမာပြောပြရမယ်ဆိုရင် အရင်တုန်းက ပန်းမှုံလာ၊ စတော်ဘယ်ရီ အဲ့လို သီးနှံတွေကို ရှမ်းပြည်ကနေရတယ်၊ ကားခတွေကလည်း ခုလိုတွေမျိုး ဈေးမကြီးဘူး။ အစားအသောက်ရဖို့လည်းလွယ်ကူတယ်လေ။ ဒါပေမယ့် ခုကတော့ စစ်ကြောင့်မလို့ လမ်းခရီးပါမကဘူး လူတွေရဲ့ ငွေရေးကြေးရေးကလဲ ခက်ခဲလာတယ်

"Honestly, money and transportation might be the biggest challenges I face in getting enough nutritious food. For example, in the past, we could get vegetables like broccoli or strawberries from Shan State, and the transportation fees were not much. Accessing food was easy. But now, due to the civil war, not only is the transportation system corrupted, but also people's financial stability is lost."

Interviewee from Gaza:

صراحةً شكل نقصُ الكاشِ مشكلةً كبيرة حيث " كانت الطريقة المعتمدة للدفع هي نقداً و ليس عبر البطاقة الائتمانية. هذا الأمر شكل عائقاً في وجه الحصول على كمياتٍ كافيةٍ من الطعام فكان الشخص يضطرُ إلى شراء كميةٍ زهيدة من الطعام. إضافةً إلى ذلك عدم توفر الكهرباء و الثلاجات حالَ دون مقدرتنا على تخزين الطعام. و لم توجد فترة حيث توفرت جميع أصناف الطعام في السوق ، فمثلاً إن توفرت البندروة، لن يكونَ الخيار متوفر أو سيكون سعره مرتفعاً بشكلٍ خيالي!

"Honestly, the lack of cash was a major concern, as the primary method for paying was by cash and not credit card. This constituted an obstacle in buying adequate quantities of food, as one was forced to buy small quantities. In addition, the absence of electricity—meaning no refrigerators—made it impossible to store food. Also, there wasn’t a time when everything was available in the market. For example, if there were enough tomatoes, cucumbers wouldn’t be available, or their price would be irrationally high."

One finding from our research was the direct link between economic instability and food access during the conflict. In Myanmar, the loss of financial stability, the junta’s blockade and restrictions on the transportation system have made it difficult for people to afford and access nutritious food. Similarly, in Gaza, the lack of cash and infrastructure, such as electricity for refrigeration, further limits food availability and affordability. These challenges emphasize how economic instability disrupts both the supply and demand for food, making it harder to meet basic nutritional needs.

Our stories highlight common themes of accessibility (availability and affordability), malnutrition, mental health effects, lack of external aid, and community resilience. The research shows that food insecurity is not just about availability, but is deeply connected to affordability, nutrition, and emotional connection. We gained a deeper understanding of how conflict disrupts basic needs and how individuals adapt to survive. These insights emphasize the urgent need for sustainable solutions that address economic, infrastructural, and political barriers to food security in conflict zones.

Story 7: The Hollow Kitchen

I am a kitchen. According to the dictionary, I am a space where food is prepared and cooked. To people I am much more than that. The simple pleasure of cooking a delicious meal goes beyond just preparing food for consumption; it includes the art of gathering ingredients, carefully picking your spices, and creating a satisfying meal. In addition, I am a space for community and connection. The act of cooking can be very intimate. Cooking for your family, your lover, your friends, can be a way to express your affection and care. Cooking with your loved ones can be a bonding experience, requiring teamwork and cooperation.

I am a kitchen in Gaza. According to newspaper headlines, I am either empty, dusty, or bombed to the ground. While this might be true for some of us, there is more to the story. I used to be a place of comfort, providing a space to find entertainment in cooking. I was bustling with ingredients, cans and cartons in my cabinets while fresh produce lined my counters. I was filled with pots and pans, laying scattered with food residue stuck to the sides, others hidden behind my cupboards but not having to wait long to be used. One of my most trusted friends, the refrigerator, has been with me forever. I love seeing her dutifully keep fresh products cold and conserved, her door opening multiple times a day, sometimes without anything being taken from her. I am a kitchen in Gaza after October 7th, 2023. I used to be bubbling and bursting with all the good things life had to offer, but things are different now. My closest friend has not been herself in a while, her corner looks darker than it used to, as if cast in shadow despite the sunlight filtering through the window. Her door remains closed, shelves and drawers deserted, her heart empty. The stove, too, has lost her spark. We have tried to reignite her flame but to no avail. For a while there was still a bag of wheat in the corner, but she disappeared quickly and did not return. My insides also feel hollow, my cabinets lighter, and my counters emptier than ever before. No bowls lined with a layer of crepe batter in my corner, no pans cooling on my stove, no flour residue on my floor, no dirty dishes in my sink. I feel empty. I used to be a space for pleasure, now I am a space filled with stress and exhaustion.

I am a kitchen in Gaza after the cease-fire. The past two months have been the darkest of my life. I am created to prepare food, to inspire joy, to bring people together and I have not been able to do any of it. I have felt useless. Recently, I have been doing a little better. Some of my friends have joined me again, there is a new bag of wheat in the corner and some preserves in my cabinets. I still feel hollow, but at least something is there now. It is still difficult for me, because none of my friends come together like they used to. There were times when the eggs, the flour, the milk, and the butter would all dance with the bowls, the pans, and the plates. The smell of crepes would fill me and the sound of laughter would reach my every crevice. I am a kitchen in Gaza and I beg you, please appreciate the blessing of having food.

Story 8: The Forgotten Fruit

I dump my life savings on the table in front of me. I was saving for my future, to go to school, to take my exams, to have a place to live, so I wouldn’t have to worry so much. But now my money has become almost worthless and I have to use all my savings just to have enough to eat. I was never rich but I lived well enough and money was not an everyday stress. But ever since the military coup in 2021, my family and I have been absorbed into the lower class. You are now either rich or you have next to nothing.

I gather up the bills and coins, put them in my pocket, and head to the shop to see what I can afford. The Kyat weighs in my pocket, feeling like more than they are worth. When I enter the shop people move around grudgingly and slowly; we are all exhausted from the constant worry that plagues us. The aisle with fruits and vegetables is almost empty, what is left is priced so high it would take my money for the whole week. I used to love eating broccoli and strawberries but since the transportation systems have broken down they have not been delivered from the Shan State, and now I barely remember their taste. I turn and grab the instant noodles instead, the cheapest thing the shop has, and what I have been eating for the past week.

As I walk home I tire quickly and feel uncomfortably bloated, finding it difficult to concentrate on anything else. The unhealthy food I am forced to eat is already taking a toll on my body. Caught up in my thoughts I barely notice anything happening around me until I step on a piece of paper. I bend down to pick it up, requiring more effort than it should. On seeing it is a flyer from the World Food Program I immediately drop it again and move on. These organizations claim to help us and give us food but I still have nothing while they get all the benefits! They don’t really care about us and neither does our government.

Before going home I decide to stop by my friend’s house. Mid knock he swings the door open, a huge grin on his face, pulling me inside. “The youth organization has just come by with a donation of fruits and vegetables!” he exclaims. His grin is contagious and quickly spreads to my face as I produce my noodles from my bag and we get to cooking.

A local grocery vendor in Myanmar selling vegetables and meats by bike.

Hnin Wai Si.Ray via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0 (2023)

Group 6: Physical Environment

Written by Savanna Raidt (based on work with Victor Xie, Emma Rosekrans, Sai Han Htun, Swe Zin Ya Oo)

For our research, we interviewed young adults from The Hague, Netherlands, Rottenburg, Germany, Beijing, China, and Kyaukme and Aunglan, Myanmar.

Research showed that different types of green spaces influence the kinds of physical activities that take place. Urban parks are associated with more vigorous activities, such as sports and cycling, which promote cardiovascular health and stress reduction. In contrast, agricultural green spaces are often linked to less intense activities, such as gardening, and may not support cycling or other high-energy exercises as effectively. The design and features of green spaces, including the availability of sports facilities and equipment, significantly affect their use for physical activity.

Socio-economic and demographic factors also influenced how green spaces affect physical activity. Individuals with higher socio-economic status are more likely to live near green spaces, but this does not always result in increased physical activity. Studies indicate that socio-economic status affects the benefits of green spaces, with those in lower-income areas potentially benefiting more from improvements in local green spaces.

Furthermore, the perception and use of green spaces varied across communities, with some ethnic or demographic groups having lower awareness or access to these spaces, leading to reduced participation in physical activities. However, the relationship between green space and physical activity was not always straightforward. Some studies showed that proximity to green space did not necessarily correlate with increased physical activity.

We chose to tell the stories from the perspective of collective green spaces across these four countries, and the interview structure we are following is the petal structure. This means that all our individual stories circle around one central aspect, which, in our case, is the relationship between green spaces and physical activity. Further, we incorporated the individual stories we collected into one story, told by the green spaces. Therefore, the uniqueness of the stories could be preserved, while also highlighting recurrent and similar themes we found.

In conclusion, while we found complex studies on the relationship between green spaces and physical activity with different results from studies conducted around the world, our own results show that there is a significant correlation between the two. Our collected stories show how deeply intertwined they are and highlight in what ways green spaces contribute to physical activity.

Story 9: We Are Green Spaces

We are green spaces across the world, all similar but also different everywhere. We witness all kinds of life happening between our lush green growth, and our fresh embrace is open to everyone. There are birds, small animals in the ground, insects, and an abundance of plants, but today we will tell the story of the young humans in our midst. Do you hear their footsteps on the grass? Would that be a city runner, someone looking for inner peace, or a group of friends, laughing within our trees?

We are central to well-being: by offering a space to escape from the busyness of cities such as The Hague or Beijing, by providing an opportunity for recreation and retreat, and by encouraging physical activity.

All of us are familiar places, people grew up among our trees. First with family, later with friends, aside from physical activity, it is important that we facilitate a safe space for all kinds of social interactions. Our branches and leaves bring shade to those living in warmer climates. Not all of us are used in an equal way/amount, that depends on the climate and environment we lie in.

In The Hague, more than in other locations, our use is dependent on the weather: Dutch winters do not seem to encourage humans to visit us, but if they do, they mostly enjoy running and strolling around. Parks and urban green spaces invite young adults to hang out and experience some nature, while staying close to their homes. I can say from experience that accessibility, safety, and attractiveness are of the essence. The aspect of attractiveness includes the cleanliness of the space, as people usually prefer clean spaces without too much trash. How safe I am perceived to be, both in the Netherlands and Germany, as well as in China, influences the use of green space. Feeling safe encourages our use at all hours of the day for all sorts of activities. In Germany and Northern Myanmar, where people further highly value the positive effect we have on mental health, and our help in relaxing and combating loneliness and stress. We also support people who need to “unplug from work and family pressures.

While to some, using green spaces is an active choice, to others, it is a natural part of their daily lives. In Southern Myanmar and Germany, we are closely intertwined in people’s neighbourhoods, accompanying children on their way to school, and offering a space to meet and play and chat with loved ones. Where else would they want to meet if not in our safe surroundings? Despite different cultures, we are important to everyone’s health and well-being, whether physically or mentally, and we are happy to share our regenerative, calming, and fresh life with people. We like to listen to their laughter with friends, their deep breaths of fresh air, and their calm heartbeat that results from being immersed in nature. We hope to see you soon and share our green abundance with you, whether you are in Myanmar, China, Germany, or the Netherlands.

The lake at People's Square and Park, Yangon, Myanmar.

Thomas Woodtli via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0 (2016)

Group 7: Social and Community Context

Written by Eve, Kevin Li, Mare van Nierop, Sieb Kooijman, and Robutham

Our social contexts can help shape and reinforce behaviours. Just like institutions such as school impose an order into our days, so can our family and friends by influencing what we do. But what happens when those structures fall away? We interviewed seven students from different parts of the world to hear the individual experiences they went through when they were socially isolated and how that affected their health physically. From lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic to armed conflict, every story we had the privilege of listening to is unique, and we can only share a fraction of what these people experienced.

Many of the physical health effects can be traced back to the mental health state of the interviewees, but it was not just the loneliness that caused these habitual changes. When people are afforded the freedom to use their own time, it is often an exhilarating feeling. But those socially isolated oftentimes have nothing to work towards and thus feel stuck and unmotivated. Sleep is one prime example, as a small decision to stay up late once can evolve into a situation of waking up later and later, with regular naps, and thus pushing bedtime into the later hours of the night too.

The sudden shift in lifestyle also manifested through irregular meal patterns, increased snacking and altered food choice. Through the experiences of interviewees, we analysed how social isolation reshaped their relationship with food. Even in challenging situations, these experiences underline the crucial part of maintaining structure in everyday life. Whether it is choosing nutritious snacks or setting mealtimes, small steps can make a big difference to lasting positive changes.

We decided to use a storytelling approach to make these effects more approachable, drawing on multiple perspectives like that of a calendar or the charging of a phone. The goal was to create a narrative that could represent the lived experiences of our interviewees while remaining distinct from each individual. With that, we could visualize the causes and effects of social isolation in a more comprehensive manner, while providing an engaging story that every person can relate to.

Underpinning all of that is the loss of routines and how this can lead to unhealthy habits developing and eventually spiralling out of control. The effect that the social environment, or lack thereof, has cannot be understated. Be it set mealtimes with the few people one is living together or someone’s friends convincing them to stay up late online. Ultimately, our research highlights how social isolation can significantly impact physical health, demonstrating the deep connection between our social environment and overall well-being.

Story 10: Physical Health Effects of Social Isolation Among Adolescents

Some do not realise, but our agendas and calendars are double-sided. We write our activities down in them, they watch us from our bedroom wall: wake up, change, study, sing, listen to music, work out, call with friends, wander, daydream, eat, drink, laugh, cry, love, go back to bed, sleep – they see it all. One could even compare it to the telescreens from George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, with the exception of their oppressing abilities. Similar to Hall & Oates’ Private Eyes, “They see your every move.” However, their existence can be quite boring most of the time, as many routines create an endless spiral of homogeneity.

Week in, week out, one’s agenda and calendar have to undergo the same – boring – routine. A sudden hick-up is thus seen as a pleasantry, an escape from the usual. Sieb’s calendar experienced one of these hick-ups on the morning of March 17th 2020. Weird, he did not go to school that morning. Was there a holiday? No. Was he sick? No, again. Weird, the calendar thought. The following day, he stayed in as well. The day after, it was still the same. Around a similar time, some two weeks after Sieb’s calendar experienced irregularity, Mare’s did as well. Where she would usually go on her occasional hike, this time she did not. And again. And again. It must be said, agendas and calendars have quite the primitive mind. A lockdown certainly did not ever cross their minds. But as time went on, the collective hive mind shared by the calendars figured out why people around the globe changed their routines.

One thing that confuses agendas and calendars is the change in sleep schedules. Have we suddenly moved into a new time zone? Eve, Hesham, Kevin, Lama, Mare, Robutham and Sieb – their sleeping schedules have all changed. Eve, Kevin and Sieb went to bed later. Lama, Mare and Robutham spent more time in bed. Hashem slept less. And the friends, oh the friends: where did their faces go? The friends of Eve, Kevin, Mare and Sieb, at least they could be heard; from their phones, laptops or things similar. But Hesham, Lama and Robutham’s friends could not even be heard.

Another thing the agendas and calendars noticed was the change in clothes: it seemed like sports clothes were no longer trendy. But as time went on, the calendars realised that there was something else going on: there was a lack of exercise. Mare, loving her hikes, suddenly stayed inside a lot more. Sieb, a football enthusiast, did not pick up his cleats anymore. Kevin did not have his sports classes anymore. Robutham did not find the energy to exercise. But out there, there was someone who did break the mould: during her period of social isolation, Eve kept walking every morning and exercising every day.

Conclusion

Health and well-being are so deeply intertwined with our hopes and fears. As Amartya Sen indicated health is needed to achieve many freedoms in our lives. The ability to be healthy and then use that health to travel, play, love or seek employment is a personal and collective experience as shared in these stories. In global health, we focus on technocratic solutions to intractable problems such as poverty or food insecurity. But we know what the solutions are: to end conflicts that continue to devalue and destroy dreams and desires.

The exchange was not without problems related to technology and finding a shared language. While all were university students, LUC with its focus on small-scale intensive education provided to be a different experience for students from Myanmar and Gaza; many had not presented before in university settings. Many struggled with an open-ended assignment. And many struggled with the on-going conflicts that impacted their ability to join the Zoom sessions.

Over the course of 7 weeks, the groups went from the initial tepid “hellos” to more comfortable conversation and dialogues. How do you acknowledge the conflicts but also focus on the learning? Finding shared understanding and a common goal was critical. While our lived realities are different, we are also very similar in our quest for learning, understanding as attested to by these stories. Students expected to find differences and while they did, they also found commonalities whether it be a mother’s emotional journey in pregnancy or the use of green spaces. Sitting in this place of friction and surprise is where learning and understanding happens.