Tiajungla Soyah of Longkhum Village, Mokokchung, Nagaland was born in 1936. She is the second of the 10 children (7 sons and 3 daughters). She is 81 years of age at present. The interview was done at Tiajungla’s home in Dimapur dated 15/9/2017.

Only two people were present at the time of the interview. i.e, the interviewer and the interviewee. The interviewer was Tiachenla Imchen, Research Assistant to Rakhee Kalita Moral at Cotton University.

THE INTERVIEWER: How old were you when you joined NNC (Nagaland National Council)?

TIAJUNGLA SOYAH: Since I was a kid, I was involved like in the youth movement and doing small things when the elders asked me to. People were always at home, along with my brothers we did stuff like, to take things from one place to another and other meager activities. But my hand to be directly involved in the NNC was in the year 1962.

THE INTERVIEWER: When you decided to formally join the NNC were you stopped or discouraged by anyone? Maybe on the basis that you are girl or maybe you are physically fit enough?

TIAJUNGLA SOYAH: No. No one stopped me. In fact during the very bad times and when operations were carried out in the villages, to gather food and rations for our men in the jungle, to carry and spread news, during such times women role was very important. The leaders of the villages asked us to look after the wives and the children of those whose husbands were away fighting. We had to cook and transport the food quickly for the safety of the village. There were Naga Safeguards, Naga Homeguards and Naga Federal Army. Women Empowerment (laughs) and like those stuffs as such did not exists. We worked alongside one another. There were females who were in the Naga army as well. They were trained like the men were, and in the jungles these women would stitch torn uniforms as well. These women seldom came home, they lived in the jungle regularly. There were many women from the Angami, Chakesang and Sumi tribe. Two women were also there when some of the Naga Army went to Pakistan (present Bangladesh) to take guns and ammunitions.

THE INTERVIEWER: Which year was this?

TIAJUNGLA SOYAH: I am not clear of the year…I think it was 1962. The lieutenant of the troop was a small girl and the biggest was nearly 6ft tall. There was a big river along their way. They were attacked by the Indian army. The only way to escape was to jump into the river. Fortunately no one died.

THE INTERVIEWER: Have you ever shot a gun?

TIAJUNGLA SOYAH: (laughs) No I haven’t. The civil went to the camp only when necessary and in the camps during duty we were also given guns. Sometimes we needed it for self-defense so during such times I have shot (laughs).

THE INTERVIEWER: As you have told me that women and men were treated as equal, what do you have to say in the present issues relating to women?

TIAJUNGLA SOYAH: For instance if we look into the recent issue of women reservation, women shouldn’t be stopped in participating in the election but when too much is given to women, there is something in us that is far worse than men. I saw this after my time in NNC. I say this because I have seen women leaders in the market areas threatening whose threats are above the threats from men.

THE INTERVIEWER: During your time in the NNC, what according to you has been the biggest contribution?

TIAJUNGLA SOYAH: I think it will be with mobilizing people from different areas. […]

THE INTERVIEWER: I often tell my father that if I was born 50 years back or so, I would have been in the underground. He always tells me that time has changed, then and now is different.

TIAJUNGLA SOYAH: At present, they (people in the underground) join because they are lazy and do not want to work at home. They know only how to lie and cheat. Even those who have been in the underground, they forcefully take. Decades back, one in 10 families will volunteer to join the Naga army. And these 9 families will help in providing his/her needs as well the volunteer’s family especially in terms of working in their field. But everything has changed.

THE INTERVIEWER: What was the opinion of your parents regarding the involvement of you and your elder brother in the NNC?

TIAJUNGLA SOYAH: They had no objection at all. All of us actively joined the movement (laughs). Since, all the family members were involved, the army came checking our house day and night. My father was often taken to jail. THE

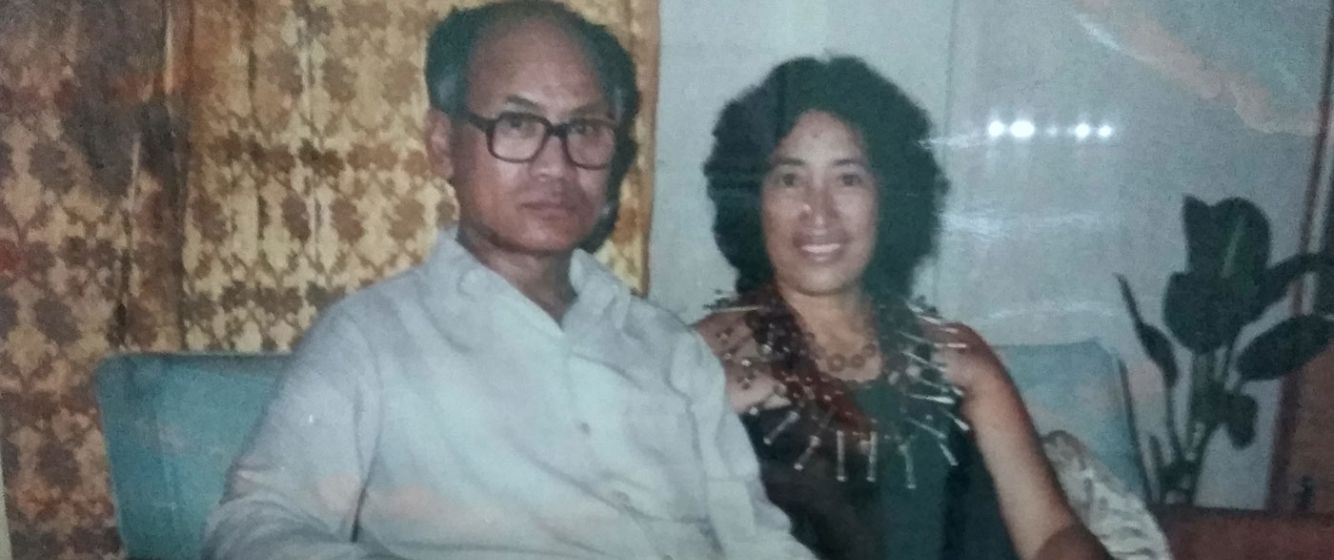

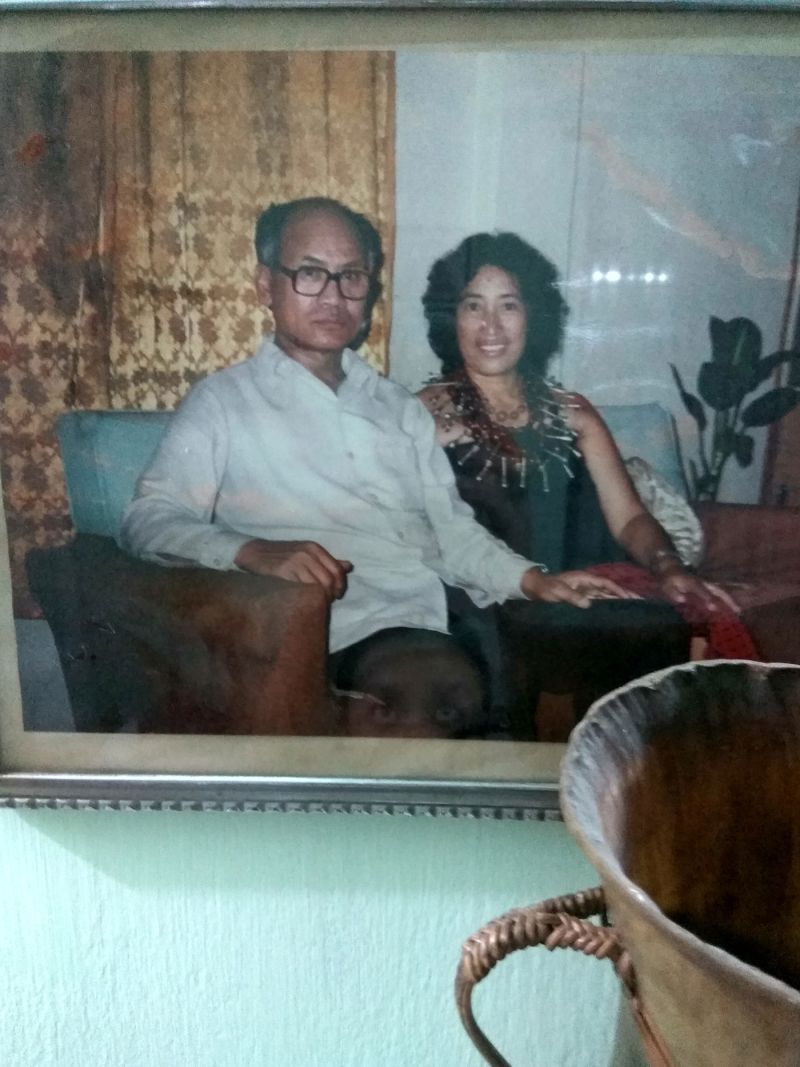

Tiajungla Soyah at her house (September 2017)

INTERVIEWER: Do you sometimes miss your time being involved in NNC, trekking the forest and other activities that you used to do?

TIAJUNGLA SOYAH: I do. I just want to roam in the jungles. I do not like the environment that I am living in right now.

THE INTERVIEWER: After the NNC divided into NSCN-IM and NSCN-K, were you involved in any of the groups?

TIAJUNGLA SOYAH: Not at all! I struck out my name after the divide and just stopped getting involved. The Shillong Accord will not be good so people told my husband to go for the talks as meeting Phizo was very difficult. The people who cared for us told him that me, his fare, food, and stay everything will be looked after. But Muivah came in between and took everything; we had to sell our house. My nephew who lives in Kohima allowed me to build this small house in his land. (Pointing to the tiles on the floor) he even put this here and in my room. The tiles have made it easier to sweep the house.

THE INTERVIEWER: You live alone? No helper?

TIAJUNGLA SOYAH: Yes, I live alone. (Tiajungla Soyah starts coughing and excused herself from the room. Returned approximately after 10 minutes to the living room with a glass of juice. She laughs and tells me of her health issues) […]

THE INTERVIEWER: Grandmother, during those times, did the females receive less suspicion from the Indian army for being involved in the Naga nationalist movement?

TIAJUNGLA SOYAH: Of course, they suspected! When there were duties we would go along with the Naga Army. It’s just that we did not live in the army camps together but when we had go to the forests, we went together. We also guarded the camps in the forests. Most of the time we lived with the groupings and not in the villages and those time when I was in the village, since my father was often taken to jail, I was the one who goes to visit him. I think it was in 1959 or 1960, all the Nagas who were giving shelter and help to the underground was put in jail in Medzhephema (Khas Pani). P. Shilu Ao was the Chief Minister then. My parents, your great grandfather were all locked up and were not allowed to meet anyone. It is just recent that I began to think how my parents were able to make arrangements for me to meet them. It was in the year 1961, I had gone to Guwahati with the Ao choir group. While I was returning I got down at 12 o’clock at midnight in the Dimapur train station so I could meet my parents. There were only Indian armies, no females. My friends were going home via Meriani and Amghuri. I was with my bedding and a small bag. I was so scared that I just sat on the bedding in the middle of the station and did not move. Even the few civilians present there were speaking Manipuri language. I did not even know when morning came because I was inside the well-lit station. I was so scared to go out of the station (as it was) full of the Indian army. In the morning two young men came to me. I guess they pitied me. One of them had big ears. Maybe God talked in their hearts to help me. They approached me and asked, “Sister, where are you going?” I told them that I was going to Kohima, but they told me that there was no convoy which was going to Kohima that day. Those two men were going to Kolkata. They asked me if I knew anyone I said I don’t. Since I have never been in Dimapur that time, I did not know any hotels either. They called a coolie for me and directed the coolie properly to take me to a hotel. […] If I waited for the convoy to go to Medzhephema, I might not be able to meet (my parents). The person who took me around offices in Kohima took me there (where the officer in charge of the prisoners was). We waited for the officer in charge in the office to arrive. He did not show up so we went to his place. The officer has no intention of coming to the office that day. He was playing caroms. The man with me said, ‘”Sir, we came to meet you.” Why would I call him “sir”? (Laughs) The officer replies angrily, “What for?” (She imitates his harsh voice.) When he was being rude, I slowly walked up behind the man. The officer saw me; maybe he saw a girl and cooled down a little. Then he asked, “What do you need?” We came here to ask you a receipt because the Chief Minister told us that you will give it to us. He ordered us to wait up in the office then as we were leaving, we again received orders rudely to wait. That person only gave orders. (Laughs) He took us to his car, opened the door and ordered us in his harsh voice “Get in!” I told him that the office is near, we’ll come up walking. The officer orders again, “Get in!” Since the ‘Sir’ is ordering (laughs sarcastically), I got into the car. He asked me the purpose of the visit and commanded that I should speak in Assamese. I argued back that I will not speak in Assamese with my father. He yells saying, “Who are you?” I replied, “I am my father’s daughter” (laughs). He was a person full of himself and looked down on people. I did not like him. […] After I took the pass I went to meet Shilu (the chief minister) again. He told me as well that I should speak in Assamese to which I replied I will never speak in Assamese with my own father. So, Shilu told me that I couldn’t meet my father. If that is the case. I told him blantly that I won’t.

THE INTERVIEWER: Were you not scared to scared to speak to the Chief Minister in a very informal manner?

TIAJUNGLA SOYAH: Before, he became the Chief Minister, we were neighbors. He often met with my father and I was the bridesmaid in his wedding (laughs). I told him that I would rather not meet my father than speak in Assamese. I walked out of his office. The man who was with me the whole time grabbed the pass and followed me asking me to talk in Assamese and meet my father. To which, I denied again. The jailor happened to the friends with the man so I requested him to pass the change of clothes and pass the news to my father that everything is good at home and not to worry about anything.