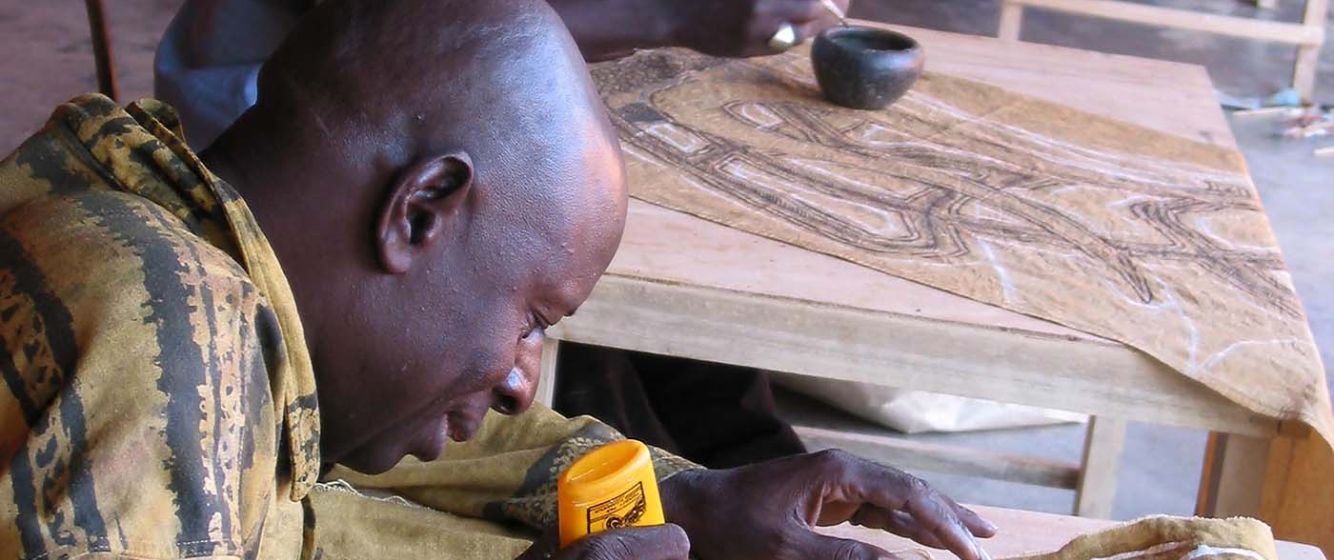

Klétigui Dembélé (far) and Kandioura Coulibaly (near) are working on bogolan paintings. Photo by Janet Goldner, 2005.

Lifelong learning with indigo in Mali: Seeing blue and more with Groupe Bogolan Kasobane

In December 2019, the Institute of Humanities in Bamako initiated conversations with a central figure of artisanal indigo dyeing and artistic creation in Mali, as part of their wider interest in understanding the role of indigo as a pedagogical tool of social transformation, under the Humanities across Borders programme.

Indigo, as well as other dyeing plants, constitute the foundation of traditional textile production in Mali. Indigo, in particular, has played a pivotal role in structuring an endogenous value chain in local and regional systems of production. To some extent, it has fashioned some trade routes crisscrossing today’s West Africa: from the Guinea-Mali road in the southwest to the Mali-Burkina-Côte d’Ivoire triangle in the south and center. The ‘indigo arc’ spans the savannah region of a historical heartland, in which migration, trade, and the continuous introduction and adaptation of new tools and techniques structured relationships of economic and social interdependency. Yet, exploring the technical, economic, social and spiritual dimensions of indigo cultivation, processing, dyeing, and commercialization beyond the few artisanal households has been a very recent phenomenon in the region. How did this space of diverse and complementary livelihood practices associated with indigo come to public attention? Who were the protagonists in Mali?

Born in Zerbala, Koutiala (Sikasso), in southern Mali, Klétigui Dembélé is a pioneer plastic artist and herbalist. As a founding member of the ‘Groupe Bogolan Kasobane’, he belongs to the generation of Malian art students, who, after independence, rebelled against the curriculum inherited from the colonial school system. As he attended the National Institute of the Arts in the 1970s, practices in graphic arts, kept in lockstep with the French syllabus, still relied heavily on imported material, tools and techniques: canvass and other art paper, watercolor, paintbrush, etc. Created in 1933, the National Institute of the Arts itself was initially a center dedicated to training in arts and crafts in the colony then called ‘French Sudan’. It became an art college in 1963 and quickly turned into a center of excellence for young music and visual art students. To date, many of its graduates have become internationally renowned artists and musicians. In the spirit of the time, some formed collectives to experiment with new techniques based on ancient practices.

One of them, Groupe Bogolan Kasobane – five men and one woman – advocated the introduction of textile and dyeing traditions into the visual arts curriculum. By that time, with the economic crisis deepening after the great droughts of 1972-1974, imported material became too expensive, and the supply lines uncertain. However, beyond material considerations, the return to the roots was a daring act of cultural self-assertion and intellectual responsibility on the part of the younger generation. To them, the program was bound to perpetuate the path of dependency and economic extroversion inherited from the colonial era.

Still, in order to successfully subvert the established order, the activists had to find viable alternatives. This is how they turned to the materials and tools used in different local traditions. Groupe Bogolan Kasobane itself included members of the Soninke, Minianka, Fulani, Dogon, Bambara, and Malinke traditions of textile production and dyeing. In this regard, it represents a microcosm of Mali and, to some extent, West Africa, when it comes to textile and dyeing practices. Klétigui Dembélé comes from the Minianka region in southeastern Mali bordering with Côte d’Ivoire and Burkina Faso. It is located at the crossroads of Bambara/Jula, Senufo and Fulani cultures. Unlike most parts of the country, the area is well watered and rich in tree and plant species. Its forests, clearings, crop fields and grasslands provided him with an initial open-air apprenticeship as well as a lifelong learning environment. In the mid-1970s, interactions with other art students awakened him to the value of his early initiation to the knowledge about plants. For example, learning their properties covered the full range of possible uses: as food or decoration; as medication or poison; as daily stimulant or hallucinogen in special rituals and ceremonies. The learner acquired holistic skills that could be deployed in ordinary and emergency situations. Dembélé’s traditional training started accordingly, and his college experience coincided with a period of intensified activism toward decolonizing the curriculum, especially the arts and crafts syllabi. These circumstances enhanced his own determination to continue his ‘village’ schooling as herbalist and dyer in Bamako. The exchanges with classmates and future members of the collective encouraged him to experiment further with plant varieties from other parts of Mali.

This way, from 1978 on, the group focused its research on natural dyes. In the first phase, they did a survey of the raw materials and local tools used to produce colors. Dembélé thus describes the starting point: “We have done research on traditional techniques. These are natural colors [extracted] from ingredients that are found here. The [ngalama] trees grow here, the cotton is cultivated here, the cotton is ginned, spun and woven by men. So, you see, we have all the technical support at hand. With regard to tools, we do not need modern brushes. We can cut and split thin bamboo stems, or palm twigs [palmyra tree]. We work with spatulas ordered from our local blacksmiths, who design them for us. As for the clay, we have plenty of it here in Mali. So you see, absolutely nothing comes from elsewhere”.

Klétigui Dembélé is working with ngalama that is in the clay jar. It is green because the ngalama leaves are still in the dye bath. The small blue basin at his feet has the strained ngalama dye (without leaves). The cloth in the blue basin is beginning to be dyed with the ngalama. Photo by Janet Goldner, 2005.

Urbanizing the bogolan

By all accounts, Groupe Bogolan Kasobane’s collective work on the bogolan technique laid the groundwork for the worldwide popularity of this material two decades later. The Bambara word bogolan is a combination of bogo, meaning ‘clay’ and lan, a suffix of agency. In this regard, the term ‘mudcloth’ dyeing is an unfortunate misnomer given that the process has nothing to do with ‘mud’. Traditionally bogolan was women’s work. With urbanization, men took it over.

The name Groupe Bogolan Kasobane by itself signifies the team’s initial dedication to a traditional dyeing technique used mainly by craftswomen in villages across southern Mali. It involved immersing cotton cloth – from strips sewn together – repeatedly into a vegetal decoction, usually of leaves of ngalama (Anogeissus leiocarpus) or cangara (Combretum glutinosum). The leaves and barks of a few other plants can be used to produce particular colors. Still, the ngalama is the dye commonly used to bond the clay to the white cotton cloth. It has a high tannin content and functions as a mordant, which is necessary for most natural dyes. The cloth is dyed with ngalama multiple times before the clay – from a pond or riverbank – is applied to draw patterns from a repertoire of signs and symbols. Once the cotton cloth is dyed with ngalama, it takes on a brown color. The clay gives the cloth a black color. Bleaching the cloth back to the original white color produces the white in the finished cloth. This often results in intricate patterns of geometrical figures, symmetrical or asymmetrical, uniform or mixed, but always an elaborate ensemble.

Traditionally bogolan comes mostly in black (clay) and white (cotton), but it can also be dark yellow or brown to dark red depending on the decoction used to fix colors or create them. The production process was geared toward self-consumption, though limited exchange or barter was not excluded. The production is fully controlled by the local population, from the cotton, cultivated on plots in the villages to the trees, plants and other natural dye sources and painting substances. The market used to be equally local; orders from the neighborhood or limited volumes sold at local markets. For example, traditional hunters wear bogolan apparels sewn with a battery of protective amulets; it is also a favorite costume in traditional theatrical performances like the Koteba, as well as in many rituals and spiritual ceremonies. However, the bogolan remains a cloth for everyday life. This combination of commonness and spiritual association makes it an expansive and variegated field of patterns and meanings.

By the 1990s the clay-dyed cotton cloth was further popularized by visual artists, film decorators and costume makers, especially fashion designers. Among the later, Chris Seydou turned out to be the most influential fashion maker. From Bamako to Paris and on many other international stages, he made the bogolan a much-demanded material. The new market had domestic as well as international ramifications. In Mali itself, tourism gained increasingly in importance with the relative democratization of the political system and progressive liberalization of the economy. By then, many cultural sites in Djenné, Timbuktu, Dogon Country and Gao had been added to the UNESCO cultural heritage registry. Cultural tourism grew to become a pillar of many local economies in the mid-2000s.

Market bogolan brought about its own revolution, particularly with the increasing use of synthetic dyes to expand the traditional color spectrum. But the success of the material made it prey to industrial reproduction without any compensation. There was actually no legal protection against large-scale piracy of traditional creations. So, in a tragic twist, huge amounts of printed bogolan shipped mainly from Chinese factories started invading the markets, including in Africa. One could argue that Mali’s traditional textile companies, COMATEX and ITEMA, could have spearheaded this revolution. Then, at the very least, the country of origin would have benefitted from the industrialization, even if it turned out to be at the expense of traditional craftsmen and women. In any case, by the end of the 1990s, the traditional production of bogolan was nearly annihilated.

In all this, the promoters of traditional dyeing techniques, who never prospered during the boom, continued to experiment with organic materials and colors in their work. The spun and woven cotton yarn, natural fibers and local dyes figure at the center of their efforts. These are becoming increasingly rare, and the border between natural and synthetic fibers or dyes is constantly blurring. In this regard, industrialization has had a damaging impact on traditional textile and dye production. It nearly dried the well of inspiration from which a long history of creativity, innovation and exchange had sprung. In the end, only the determination of the pioneers and guardians of the tradition helped prevent its total demise. Research and social engagement enabled new possibilities for practitioners and scholars to reinvest in the field of experimentation and innovation.

Klétigui Dembélé tends a real botanical garden in his yard. The ngalama tree stands in the foreground, the npeku tree in the background. Photo by Karim Diallo, 2020.

Indigo in a multidisciplinary syllabus

At the International Convention of Asia Scholars in Leiden, ICAS 11 (15-19 July 2019), the roundtable ‘Place, Practice and Nature: Indigo’ shed light on the versatility of indigo in its uses in Asia and Africa. While on both continents the plant has a long history of use in dyeing, the different perspectives illustrated the need to collaborate at the regional and trans-regional levels for a shared syllabus that surpasses the habitual compartmentalization afforded by educational departments and disciplines. In this regard, the Malian team, which had so far mainly studied indigo through geographical surveys, discovered potentially far-reaching ramifications of their activities. Unlike Mali, nation-states have played a central role in promoting traditional textile and dye sectors elsewhere. In neighboring Burkina Faso, for example, after three decades of consistent policy of protecting the national artisanal cloth, faso danfani has become a value-added product sustaining many families and communities. The role of public universities in India, Taiwan and Thailand in supporting artisans was particularly eye-opening, since such university outreach work is possible in Mali too if only there is sufficient awareness and commitment. All these lessons triggered questions about a potential shift in orientation in the Institute of Humanities’ HaB research on Malian indigo and artisanal textiles. The groundbreaking work of Groupe Bogolan Kasobane inspired important exhibitions in France and Switzerland, among other places: ‘Boubou, c’est chic’, Musée des arts d’Afrique et d’Océanie in Paris and Museum der Kulturen in Basel (2000); ‘Textiles du Mali’, Museum der Kulturen in Basel and as a permanent exhibition of the Musée National du Mali (2003); ’Textiles bògòlan du Mali’ in the Musée d’ethnographie in Neuchâtel (2004); ‘Woven Beauty: The Art of West African Textiles’ in Museum der Kulturen in Basel (2009). These generated scientific publications and contributed to the growing interest in, and knowledge of traditional textile and dye.

Klétigui Dembélé’s expertise was a valuable source of information at the final HaB workshop held at the Institute of Humanities, which focused on integrating the Kasobane experience in fieldwork conducted in Mali and joint experiential activities with the research team of the Institute of Social Studies (INSS) in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. To this end, the two HaB partners signed an agreement to coordinate their activities more closely. Thus, ahead of the late-2019 workshop, the Institute of Humanities team met with Klétigui Dembélé on different occasions to debrief him on the ICAS experience, from the lessons of the pre-conference experiential school ‘Reading Leiden’ to the ‘indigo soup kitchen’. In return, he presented the genesis of the Kasobane collective, the initial impetus to not only reject a colonial curriculum but also propose a new approach, which would rely first and foremost on local materials, tools, techniques, and the practitioners of this knowledge base.

Reflecting on his personal experience, Dembélé noted that getting the younger generation interested in ancestral arts and crafts would require a different approach. Present-day students grow up away from the fields, looms and dye pits, so they need a more structured introduction to traditional materials and techniques. While in the 1970s students had to fight to be allowed to use bogolan and indigo, these materials have become standard in use, if not taken for granted. These days, Mali has two established public art colleges, the National Institute of Arts and the more recent Conservatory for Multimedia Arts and Crafts, where, for example, indigo could be taught, researched and further refined in its uses. New varieties and techniques learned from other countries, from Burkina Faso to Taiwan, India to Thailand, could be tested and compared. Still, the focus would remain on the local terrain: “Students before graduation could at least go out and conduct field research on the [indigo] plant. They could then present the results through original drawings and patterns they will have created”. To him, this approach is all the more urgent since college graduates, especially in the arts, nowadays face massive unemployment after graduation. With sufficient sources of raw material still at hand, young practitioners can learn ancestral techniques, develop their personal styles, and bring about innovations that could enhance the artistic quality and commercial value of indigo and other dyed textile creations. In passing, it is paradoxical to note that the Conservatory is presently more in favor of going back to European painting techniques and materials and multimedia than to explore the potential of indigo plants, dyes and dyeing in its curricula.

A scarf dyed blue is hung to dry in the open. Photo by Karim Diallo, 2020.

A localized strategy of indigo preservation

Yet Mali’s rich and diversified plant and forest cover has been severely depleted over the last five decades. Recurrent droughts and decreasing rainfall have set the trend, but human action plays a decisive role. Extensive land clearing, overgrazing, uncontrolled logging, poaching and bush fires devastate fragile ecosystems every year. Population growth and urban expansion put constant pressure on rural land and threaten the reservoirs of biodiversity. A telling example is the zone of Siby, a traditional indigo-growing territory. Located at about 50 km south of the capital Bamako, which has long held the dubious record of the fastest-growing city in Africa, its vegetation shrinks continually. Since the construction of the paved road to the border with Guinea in the early 2000s, Siby has suffered from speculators keen on acquiring land to develop houses, camping grounds and commercial farms.

Additionally, affluent city dwellers increasingly buy plots to build country homes with gardens and even stables to escape the stifling pollution in town. With little control over these schemes, the result is an already fragmented landscape from which whole species have disappeared in just two decades. To be sure, indigo varieties can still be found in the wild but they are increasingly few and far between. The once abundant raw material is increasingly difficult to find in Bamako. Dembélé reflected: “Once I went to the main market to buy indigo balls. They sent me from one stall to another. In the end, no one had had any. I couldn’t find any indigo!”

This scarcity is unlikely to encourage young students to work with indigo. So, to remedy the problem, he has decided to plant domestic indigo trees: “My strategy is to grow the indigo tree. So, I send the seeds to my village, Zebala, where my relatives have enough land to grow indigo for me during the rainy season. After the harvest, they send me my crop”. This initiative is still an experiment, but it could be the blueprint for a new approach. In the end, the aim is to plant more significant surfaces and grow sufficient indigo to cover the different needs. Cast in the ‘Humanities across Borders’ framework, it can be the starting point for experimenting with outreach programs that are based on the long-term collaboration between an academic institution and a local community, in the way, for example, that Chiang Mai University accompanies agricultural and crafts cooperatives in northern Thailand. This way, the Institute of Humanities will work with Dembélé and Groupe Bogolan Kasobane to turn his personal strategy of indigo preservation into a larger effort to attract and commit young scholars to the revitalization of ancestral practices through documentation, experimentation and even cultivation.

Baba Coulibaly and Mohomodou Houssouba, Institut des Sciences Humaines du Mali.

Klétigui Dembélé (far) and Kandioura Coulibaly (near) are working on bogolan paintings. Photo by Janet Goldner, 2005.

Publications accompanying major exhibitions on Malian and West African textiles

Duponchel, P. 2004. Textiles bògòlan du Mali. Neuchâtel: Musée d’ethnographie de Neuchâtel. Gardi, B. et al. 2009. Woven Beauty: The Art of West African Textiles [Mali, Nigeria, Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana]. Basel: Museum der Kulturen Basel / Christoph Merian Verlag. Gardi, B. (ed.) 2002. Le boubou, c’est chic. Les boubous du Mali et d’autres pays de l’Afrique de l’Ouest. Basel: Museum der Kulturen Basel / Paris: Musée des Arts d’Afrique et d’Océanie / Christoph Merian Verlag. Gardi, B. (ed.) 2003. Textiles du Mali. Bamako: Musée National du Mali.

This article was published in the Autumn 2020 newsletter of the International Institute for Asian Studies, available online here. To subscribe to the IIAS newsletter, click here.