Terraced rice cultivation in the uplands of Northern Thailand (image: www.artoftraveler.com)

Towards a 'Rice-scapes' Syllabus: Notes on the Asian Rice-Scapes Panel at the Borderland Spaces Conference, Bishkek

At the 6th Conference of the Asian Borderlands Network, held in Bishkek between 13-15 August, members of HaB held a double panel entitled Asian Rice-Scapes: Topographies, Tastes and Technologies. Erik de Maaker and Dharitry Narzary, two of the panelists, provide here a recap of the papers presented at the conference, as well as notes on the direction this discussion will take in the future.

By Dharitri Narzary and Erik de Maaker

As the prime staple of Asia and some other parts of the world, rice is an essential resource and commodity, and its control wields political power. Cultivating rice requires dedicated knowledge, skill and experience, whereas it also induces specific economies of production, taxation, and consumption. In a cultural context, rice provides a foundation for tangible and intangible heritage that communities identify with in the rice-growing world. What can it yield (to use an agricultural metaphor) to ‘think with’ rice? How might rice cultivation create ‘rice-scapes—spaces that are defined by specific modalities of rice cultivation, distribution, and consumption? Can an analytical perspective on the kind of territorialities that rice cultivation creates, and the sociological configurations these involve, serve as a starting point to explore ethnic, economic and political spaces? These are some of the questions that we attempted to explore in a double panel that we organized (Dharitri Narzary, Surajit Sarkar and Erik de Maaker), at the 6thconference of the Asian Borderlands Research Network, that was held from August 13-15 at the American University of Central Asia in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan. Though the panel title does not suggest inter-regional conversations, the underlying commonalities of rice growing experiences have been brought to the fore to carry forward the dialogue on rice. Apart from the convenors, Mohomodu Houssouba, Malee Sitthikriengkrai and Chayan Vaddhanaphutti participated in the panel. The panel included papers relating to research conducted across South and Southeast Asia, as well as in West Africa. Wet rice cultivation, typically practiced on fertile clay in densely populated riverine plains and deltas has historically been conditional to the emergence of cities and states in Asia. Inducing trade and migration across territories, rice related knowledge and transactions have always exceeded specific polities. The high population density of wet rice cultivating areas is in sharp contrast with uplands that are used for the cultivation of dry rice, typically located at the sparsely populated peripheries of states.

The disparities between different modalities of rice cultivation have given rise to ethnic and indigenous boundaries in the rice growing world. In other words, rice related topographies frequently legitimize political borders with wet rice and dry rice cultivators located on opposite sides. These boundaries can obscure cultural, social and religious linkages. Focusing on the production, economy and culture of rice, the panel intended to explore, among others, divisions and interconnections between hill communities and plains dwellers. In what respects can histories, migrations and utilizations of rice techniques, besides the economic and religious symbolism,, contribute to the development of new perspectives on the emergence of cultural, social and political boundaries in rice growing regions?

Surajit Sarkar

Surajit Sarkar’s paper, ‘Blurring Boundaries: Narratives of Rice Cultures and Transformation’, highlighted the diversity and homogeneity in rice cultivation. The paper focussed on techniques of rice farming that ranged from upland farming in North East India (Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland and Assam) to terrace farming in central India (Chhattisgarh). He discussed the various processes of rice farming including irrigation and transplanting technique important for certain varieties of rice, seed survival, multi-cropping in swidden cultivation and optimum use of terrace farming. The practice of growing ‘ration rice’ in upland areas, developed mainly for commercial purposes, informed about transformations in rice rice cultivation. Using oral narratives as examples, these aspects of technique and practice contextualised and marked the importance of rice as food and source of cultural tradition for sustainable development in rice growing/eating communities.

Mohomodu Houssouba

Mohomodu Houssouba’s paper, ‘Asia to Africa: Mapping Seed Depletion in West African Basin’, like the first paper, focused on the techniques and various stages of wet rice farming in Senegal and Niger basin. This paper provided an interesting intervention prodding to look beyond Asian rice-scapes. The traditional practice of growing rice in West Africa is dependent on community knowledge and its oral transmission. The significance of language related to the traditional rice farming methods explained the intrinsic cultural context as found in some Asian experiences. The differences between traditional and modern methods of rice farming are an important marker of transformation taking place in rice cultivation in Western Africa, especially in the context of using rice for consumption and commercial purposes. The traditional wet rice farming is dependent on rain water while modern irrigated cultivation need not wait for rain, and these aspects affect the productivity. The sustainability of the local rice varieties is challenged due to its labour intensive nature of cultivation. The tradional rice has to be planted in pure form, separating the seeds in stages. These processes add to a longer harvesting cycle, and therefore, farmers are trying to shorten the cycle, which has an irreversible effect on the survival of the seeds. Unfortunately, there is no documentation of traditional rice farming methods and knowledge, and perhaps this project will be a step towards that direction

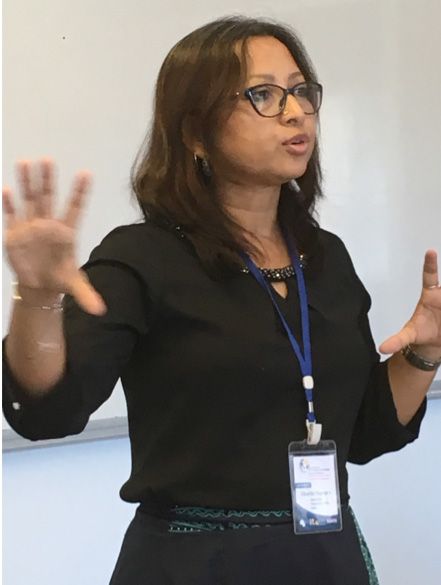

Dharitri Narzary

Dharitri Narzary in her contribution (‘Rice in the Border Areas of Assam and Bhutan: A comparative perspective’) discussed how the Bodos, settled along the Bhutan foothills of the eastern Himalayas, perceived the upland Bhutanese with whom they have had a long history of interaction. The Bhutanese are represented in Bodo folklore as plunderers of grain and other resources, and they tend to consider the Bhutanese as culturally backward. The Bodos continue to identify themselves as farmers of rice though a large section of the society has taken to other modes of livelihood. Narzary’spaper enquired how rice helps the Bodo community to articulate its identity vis-à-vis the upland Bhutanese. Is it because of the specific social and religious significances and meanings of rice for the Bodo? Or is it due to topographical differences, and its implications for people’s lifestyle, that the Bhutanese as hills people are perceived differently by the Bodo? How is rice a commodity, as a family resource, as an object with higher spiritual meaning, a metaphor as goddess of wealth (Mainao) and a lifeline of the common peasants? She explored the traditional practice of community farming, resource sharing (community produce), rice cultivation techniques, social customs and rice related cultural and religious rituals. In exploring the socio-cultural and economic contexts of rice, her paper tried to answer the question: Does the rice culture of the Bodos explain how they perceive themselves as distinct from the Bhutanese?

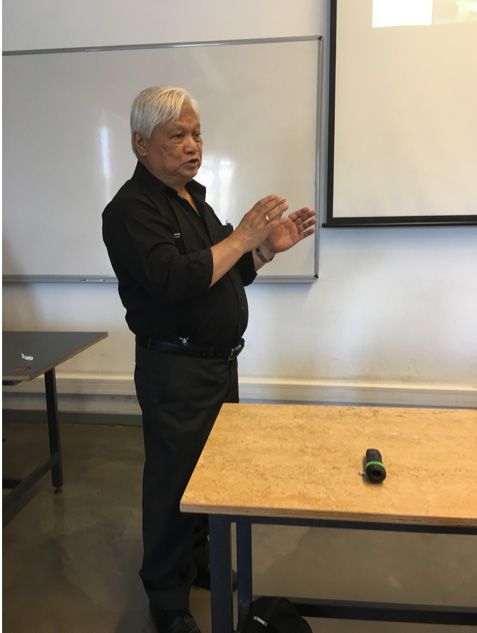

Chayan Vaddhanaphutti

Chayan Vaddhanaphutti’s paper, titeled ‘Shifting Cultivation and Shifting Power Among Indigenous People of Thailand: A case of the Lua people of Western Borderland’, presented the power dynamics in the borderland of northern Thailand through the lens of land use and forms of agriculture. Three elements in administering this power dynamics: state polity, modernity and cultivation were highlighted in the paper. The traditional livelihood practices of the Lua people, a Mon-Khmer speaking group, in their pre-modern subjectivity, were what the paper focused on. As practitioners of swidden cultivation their livelihood resources are limited but sustained by growing highland rice alongside other crops. The modern nation state of Thai marginalised the Lua people by banning the practice of shifting cultivation, as it was considered a threat to national security. This not only marginalised them as a people but also within the community the power equation changed as banning shifting cultivation reduced the influence and power of the Samang, the village head and religious leader. Banning shifting cultivation was meant to territorialize non-state spaces as part of the modern state, alongside an assimilation policy involving education and wet rice cultivation. The entry of Christian missionaries and their increasing influence further reduced the role and significance of the Samang in Lua society. The paper also discussed the issues of land use and labour in the given socio-political and cultural context.

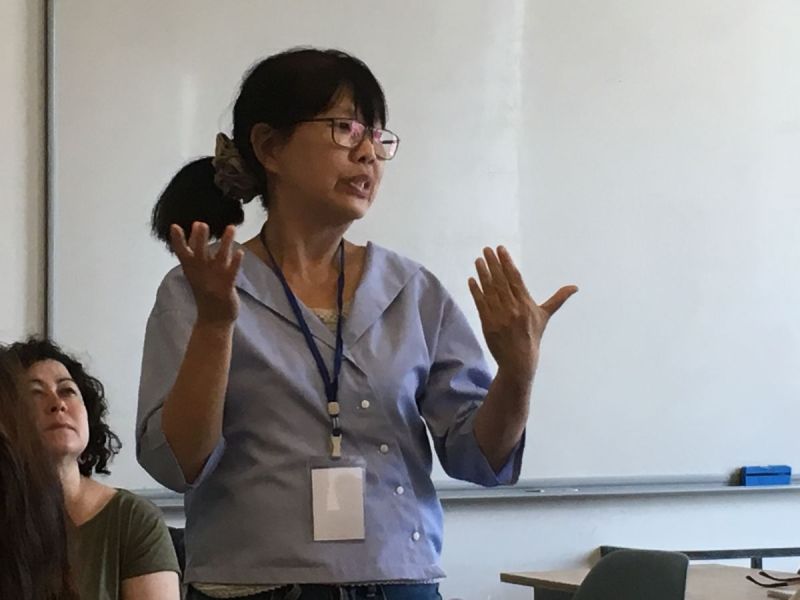

Malee Sitthikriengkrai

Malee Sitthikriengkrai’s paper, ‘Maintaining Autonomy Through Shifting Cultivation Among the Karen of Northern Thailand’ presented an interesting insight into the shifting cultivation. The dichotomy of forest conservation and swidden cultivation (which involves hacking and burning forest) is a subject debated in many parts of the world. The modern state tends to view the traditional practice of shifting cultivation as environmentally challenging and a cause of destruction of forests in upland areas, in contradiction to the beliefs held by practitioners like the Karen who maintain that such a practice contributes to revitalising the fertility of land and the forest. The tradition of shifting cultivation is seen by the Karen community as the source of Karen autonomy and RaiMunViang (upland rice cultivation) as the most sustainable form of cultivation as it draws what it requires from the surrounding nature. The paper highlighted the spiritual and symbolic relevance of RaiMunViang in sustaining the Karen identity in a modern state. Upland rice cultivation is labour intensive but is continued to be practiced as it allows the community to use forest land and resources collectively. In addition to growing rice, upland farming also allows growing varieties of other vegetables, which is not possible in the paddy fields for wet rice cultivation.

Erik de Maaker

The paper by Erik de Maaker (‘Rice as a Cultural Resource: Symbolism, Distinction and the Rethinking of Ethnic Boundaries’) argued that ethno-nationalist movements tend to derive their rationale from primordialist interpretations of ethnicity and indigeneity that suppose an idiosyncrasy of people, language, culture and territory. This perception of ethnic communities as ‘islands’ is rooted in colonial state making, and continues to inspire political mobilization, consistently advocating the institutionalization of ethnic boundaries by drafting new ‘self-governing’ administrative units, or the imposition of legal boundaries that define group membership. Over the last half a century or more politics in North East India have been dominated by movements organized along ethnic lines. One of the (many) ethnicities that this pertains to are the Garo. In the paper he moved beyond the focus on ethnic boundaries, to explore a main trope of Garo ethnicity, which is the cultural significance of rice. Archetypically, Garo are perceived as an upland people who are particularly engrossed with swidden rice. Indeed, the Garo community religion perceives rice as a source of life, the cultivation and harvest of which at once demands sacrifice and sacrilege. As economic reorientation and religious conversion, among others, redefine and transform people’s ideas about, economic access to, and technical engagement with rice, to what degree can it continue to act as a cultural resource? In what respects do these cultural practices, knowledge and ideas create a Garo cultural sphere that is distinct, or continues to be distinct from that of ‘neighbouring’ ethnicities? Following the panel, members had a very productive meeting, which helped to find direction for the project on rice. Many gaps and ideas that emerged from the panel discussion could be further developed. It became apparent that the papers explored rice from the perspective of political ecology, addressed environmental ontologies, as well as the societal hierarchies that techniques of rice cultivation and distribution can induce across societies and regions. The various cases outlined in the papers, combined, are expected to contribute to the development of a pedagogy that will create room for unconventional approaches to territory, ethnicity, society and state.

Dharitri Narzary and Erik de Maaker The panelists will be taking these discussions forward soon, at the mid-term HaB meeting in Amsterdam on 20–21 October 2018, where they will form one of the working groups discussing the creation of HaB syllabi along the themes of Food, Word, Place and Practice.