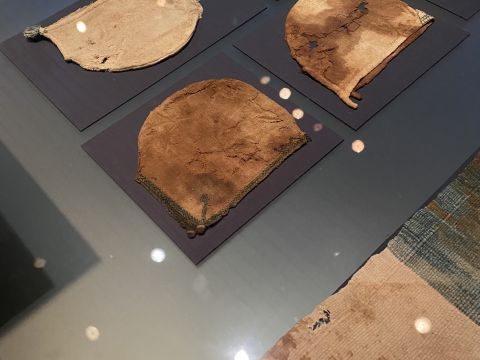

Caps From The Tellem Caves and The utility of The Museum.

These are images of caps found in the Tellem caves in Mali. They are some of the best-preserved textiles from west Africa and among the oldest yet found. They are part of a collection of finely woven and plaited objects dating from 11th- 15th centuries. For those who study African textile history, they are incredibly important as they are some of the oldest surviving West African examples of spun cotton, strip woven cloth, indigo dyeing, and certain patterning techniques still practiced in west Africa today. In fact, these caps are quite similar to these are still worn all over west Africa, including in the Dogon community that currently lives in the Tellem cultural area.

After visiting the Volkenkunde museum, I can’t help but think about the concept of collecting, the idea of the museum, and the social function that it serves in the preservation of empire. I always appreciate the incredible opportunity to look at museum collections, but I am constantly reminded of the fact it was a string of opportunities provided by a substantial amount of luck that enabled me to have access to these beautiful objects. The same opportunity is not available to many people, including many of those in my own community. I cannot deny that it is a tremendous violence that many people from the communities that were featured at the Volkenkunde may not have this same degree of access. Even when the various non-white communities whose cultural heritage is on display have access to the museum, is it any way designed for them? Or is it designed to display them?

It's hard not to see the Museum as a collection of curio cabinets filled with plundered objects taken by soldiers, glorified grave robbers, and colonial voyeurs. The non-white is a spectacle, their cultural objects curiosities that show the power of those who collect them, not those who made them or used them. One could argue the merits of making these objects available for the “world” to see, but who is the world? Perhaps it is about making these objects available for a Dutch viewership, but who is a Dutch person in the collective imagination of Volkenkunde Museum's board of directors or curatorial staff? Are they inviting people to a place where they are encouraged to enter different ways of knowing? When you enter an Indonesian or Dogon exhibit, are you encouraged to enter their world, to agree for even a short time to their way of knowing and understanding the universe? Are you encouraged to disrupt your ways of thinking and enter another ontological reality? Though I deeply believe that these are crucial questions to ask. I question whether or not any museum can honestly address them.