Aarti Kawlra

When I was 17, I withdrew from pursuing a bachelors in Chemistry. This was a conscious moment of choice in my life. I made the decision after attending a freshman course in anthropology in the US. My options were in plain sight. I still remember how my mind conjured up the image of a future work setting defined by my high school experience of lab-coats, test tubes, funnels, pipettes and Bunsen burners. The vision also fueled my rhetoric of negation for I could hardly articulate a desire for learning through conversations, travel and the lives that people lead.

That was way back in the 80’s. Since then I have had an education in Sociology at Delhi University. Of my Bachelors in Sociology, the only vision that has remained with me is that of Mrs. Kidwai who taught an entire 50 minute lecture with the aid of her notes on the tiniest of cards amidst long intervals of probing silences. Of my Masters I remember two incidents. One of Amitav Ghosh who taught us Kinship I and Kinship II, especially his stories of travels in North Africa (he was working on his first novel The Circle of Reason). The second memory is that of J.P.S. Uberoi whose Sociological Theory class (structural anthropology) was more experiential than theoretical by far. I wrote an M.Phil thesis on “Hair” under his guidance. The work involved a good measure of intrigue, imagination and library investigation as it took me through the landscape of myth, religion, semiotics, gender, politics and history.

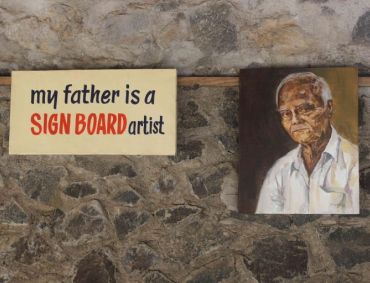

I read the Circle of Reason as soon as it came out. By the time I read it I was already working at New Delhi’s Craft Museum, spending long hours in the “demonstration area” where I could spend time with Nilamanidevi, Gangadevi, Jivyasoma Mashe, Avaaz Mohammad and so many other master artisans as they worked and talked. I met still more weavers when I took up the ‘Saris of India’ project in 1988 which allowed me to travel to 98 weaving villages in Tamil Nadu, in south-eastern India.

By the time I returned to academia to do a PhD in the early 90’s I was sure that I wanted to spend more and more time in a weaving household. I made many lasting friendships with members of the Padma Saliyar community who identify with weaving as a “hereditary” occupation. Many have passed away but I hope I will not be too late to share the published version of my PhD thesis with those who are still there. It has been a long journey and the publication process does not care about the presence or absence of these people and whether they will get to see their life retold in print. I wish it did though.

Over the years, my research engagement in the discursive spaces craft inhabits has led me to ask a whole range of questions – “heritage for whom and why?”; why is ‘culture’ invoked in the definition of artisanship?; the incongruity of artisanship within global techno-economic regimes; is craft work congealed knowledge or embodied skill? Or is it both? The field is a growing one and yet I find that as it becomes more defined, it loses its openness for lateral inquiry.

In 2010, I was introduced to the International Institute of Asian Studies (IIAS) in Leiden, The Netherlands where I found an open space for exploring craft as method in a sustained and expansive context of trans-disciplinary, trans-national/regional collaboration. My life trajectory has been more of an educator rather than that of a scholar in the strict sense even though I am currently affiliated as an independent scholar at the Madras Institute of Development Studies (MIDS) for a two year ICSSR funded project on “Craft and Education in twentieth century south India” in Chennai. At IIAS I function as the Academic Director of the “Humanities across Borders: Asia and Africa in the World” program. Here I have the wonderful opportunity to work with scholar-activist-educators in four different geographies in Asia and Africa.

Over the next four years we hope to share conversations and exchange ideas toward the development of de-colonial, de-national and ecologically grounded curricula, learning spaces and pedagogies.