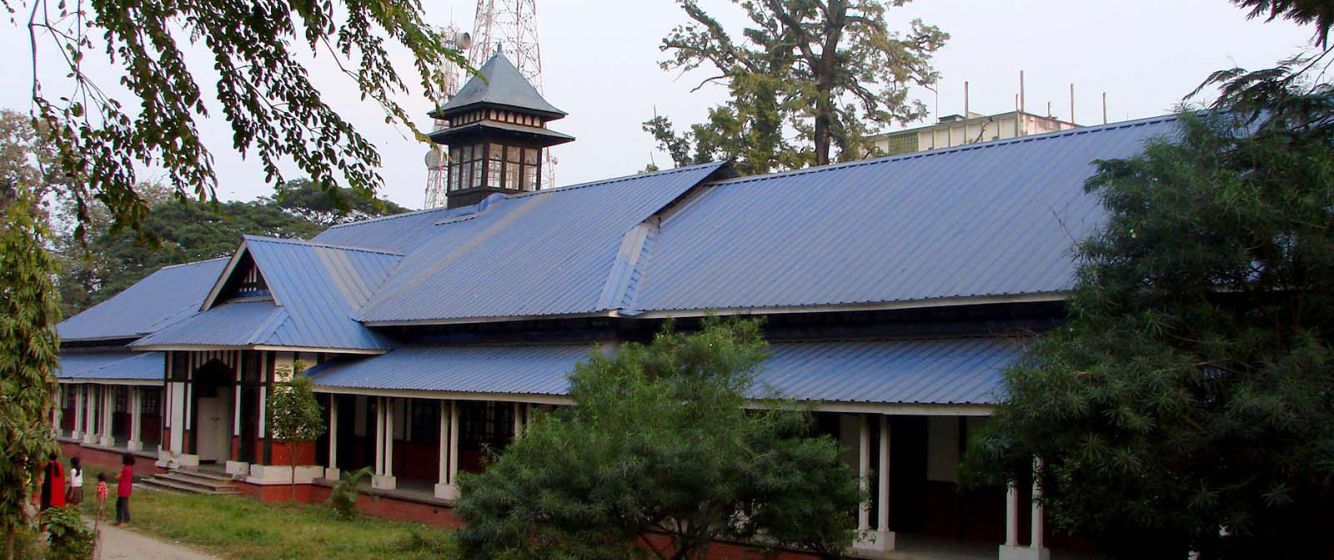

Cotton University

Cotton University is a public state university in Guwahati, Assam (2017) and the oldest institution of higher education in India’s northeastern region, established in 1901 as Cotton College, by the colonial government and named after the Chief Commissioner of the erstwhile Province of Assam, Sir Henry Stedman Cotton.

A teaching and research university, the Cotton University in its new avatar, is dedicated to building a robust knowledge-institution shaped by modern curricular methods of teaching/learning, and is thus well geared toward the core philosophy of the Humanities-across-Borders Program (IIAS- Mellon). In seeking to promote new and interdisciplinary research its vision matches the embedded learning goals of the HaB program and thrust on locally-oriented knowledge bases and community-driven research agendas. It shares HaB’s global outlook and welcomes pedagogic change and innovation among other advancements in the disciplines alongside a consortium of connected universities.

Institutional space

This shall be available in terms of the cosmos of the Cotton University that is friendly, and support from its infrastructure and academic resources. The Centre for Women’s Studies which has been recently instituted is developing a couple of programs that can find synergy with HaB’s partners in 2.0 phase beginning next year. CWS can serve as HaB’s nodal hub in Cotton University, which is also introducing the School of Liberal Arts this year. The forthcoming gender program should be able to test the curricular research tools that HaB has already developed. Our Faculty guest house can provide logistical support and hospitality for programs between partners.

Proposed Activity/ Capacity Development with HaB 2.0:

- Capacity building and HaB-directed teaching and research for CWS’s gender program/experiential schools.

- Engaging with HaB methods of curricular development for the School of Liberal Arts in BA programs opening shortly.

- Network with partners, Ambedkar University, Chiang Mai University and Myanmar University (intraregional South/ South east Asia linkages) for faculty exchange Inter-regional liaisons (Africa, Europe, US and Asian partners) for HaB summer schools / workshops/ short term joint-teaching programs

- We also envisage archive-building and knowledge repositories in this consortium of universities.

Contact persons:

Dr. Sanjay Dutta, Academic Registrar, Cotton University

Dr. Rakhee Kalita Moral, Associate Professor and Coordinator, Centre for Women’s Studies (CWS), Cotton University, and HaB Project PI