Arya Praharaj in Times of India, 27 August 2020

Reflections on teaching and learning in the time of pandemic (1): The initial months

I found that during the Covid 19 pandemic, even though most of my students had smart phones, many students were left stranded for many reasons.

The ongoing Covid 19 has been the most disruptive force that I have experienced as a person, professional and as an educator. This blogpost is a reflection of my teaching and learning in the time of Corona (it always sounds like Gabriel García Márquez’s title) more than a month after completing the semester in May, as an adjunct at Ambedkar University Delhi (AUD), a liberal arts public institution under the city of Delhi, in India. These reflections are a mix of my own experiences, those that I have heard from friends, family members, students and some of the on-going discussions. These reflections are by no means extensive and instead cover selective areas, most of which I gathered from my students and some faculty members experiencing disruptions in their educational practice. Conversing with others, especially Dharitri Narzary who is an Assistant Professor at AUD and my brother, Jeffry Jacob who teaches at Bethel University, Minnesota, helped me anchor and navigate this phase of learning on the spot and teaching, and sometimes flying, by the seat of my pants.

I found that during the Covid 19 pandemic, even though most of my students had smart phones, many students were left stranded for many reasons. First, there are fewer cell phone towers in India and subsequently less coverage. In multi-user household with limited systems, the question is about managing access and some students had only a smart phone to navigate at this time. Second, the students generally struggled to submit assignments in the form of essays, PPTs and presentations. Third, almost all the students had data budget related issues. Heavier files (uploads and downloads) consume data. Long lectures on video uploads are, thus, not good ideas nor is asking the students to upload heavy files. Fourth, lack of materials at-hand like e-books, lack of personal computers including tabs, and residence in remote areas where access to internet is limited including slow speed (which also means that the students can’t access heavy files). And finally, the emotional, financial and mental struggles of the students and faculty. I don’t think any one of us was prepared for these; and are still not completely prepared to address these. Many students’ parent(s) lost their jobs or could not work because of the abrupt lockdown. The strain of managing too much from different fronts like education, health, financial, personal, mental health and more suddenly has been something that we’re still grappling with. Additional household responsibilities proved to be a challenge for students as well as for faculty.

But the pandemic was not the only event that triggered us to reconsider and re-imagine our approach to teaching and learning. From 2019 onwards, education in India suffered from a series of disruptions–anti-CAA protests (December 2019), in which large number of students were involved either directly or indirectly (often with very little organisational/ institutional support), religious riots in North-east Delhi in February and March 2020 which was followed closely by untimely rains, and the sudden lockdown imposed due to Covid 19. Students along with their families were often forced to move back to their home towns/ villages and there was also the humanitarian crisis of migrant workers caused by the Indian government’s unplanned lockdown. The floods and cyclones have added to these disruptions.

From my discussions with colleagues at the University, it was clear that a large proportion of the faculty, prior to the pandemic, did not engage in online teaching. Instead, they had been using online methods for sharing digital resources and essential communication. Those who had used Google Classroom before, in some ways, could manage the sudden shift to online mode with some ease But even for these students a sudden shift to a virtual mode for all the courses was a balancing act because of technical lags as well as through a sudden absence of on-site teaching-learning mode with which most of the students and teachers are familiar with. As faculty we used different strategies for teaching in virtual mode with varying degrees of failure and success. Some faculty found links to the already existing video lectures/ MOOC recordings on the web, shared them with the students, and had follow up discussions. Some made recordings (audio- video) of the topic along with worksheets and used a flipped teaching approach. I did this and I discovered that my students were not comfortable or used to becoming familiar with the material beforehand, an essential requirement if classroom is to become a place where discussion and assimilation is to take place. I found it useful to video record a few of my lectures and also feedback to the assignments. This made teaching somewhat more personal where the students could see a face while looking at a presentation. At the University, we usually assign a percentage for attendance and class participation. Since both these assessment parameters were not possible, this required some creative thinking. I converted this criterion to one of processing and participation. I kept participation because I had made a point of constantly reaching out to the students individually so as to sustain the conversation and link to the learning process. Dharitri used the pedagogical tool of re-writing and re-imagining a text for her MA students. She would circulate, over Google Classroom, a text to her students which they were to read critically and write about in 500 words. Her class was active and she encouraged them to ‘comment’ over the Classroom. Some of the students found this an accessible and meaningful way of engaging with the text. We were exposed to this tool in the Storytelling and Writing Workshop organised by HaB- Kenyon College and Madras Institute of Development Studies between 19-21 December 2019.

Many of us had to also incorporate WhatsApp in our teaching and communication. The students who faced data related problems found it easier to access materials on WhatsApp. We used video conferencing platforms like – Zoom, Google Meet and one-on-one interactions to hold lectures. But these were also challenging. Stable internet connection was a major hinderance. I resorted to dividing my class in three groups while arranging face-to-face interaction (which also meant repeating everything thrice) but even in smaller groups, responses like ‘can you hear me?’ – ‘You are not audible’ etc – were all too frequent. The idea of ‘breakaway’ groups in Zoom, Teams etc was and is very beguiling but the internet related issues will keep many of us beyond this means of inclusion.

Cheryl's workstation

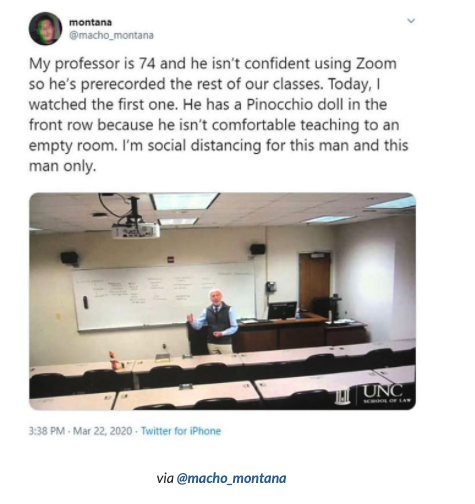

The above photograph is of my current work station in times of WfR (Work from Home), which has evolved over July. From teaching on-campus where I could see clearly the expressions and listen to the intonations of the students, and also engage in light conversations, this is the space where I have been teaching from. This space is distant and constant efforts to make it personal are sometimes successful but requires frequent re-imagination of pedagogy and ways to engage students. From almost never sitting on a chair while teaching, to sitting down in from of the computer to teach has been disconcerting, something which I am trying to manipulate to the maximum degree possible. This simple change has implications for the pedagogies and methodologies that we usually adopt. When I came across how Prof John V. Orth from University of North Carolina, as seen in the image at the end, adapted in order to ensure that his students did not miss out, I was comforted. It also reminded me of the different ways in which we, as educators, are slowly finding our feet...a move away from flying by the seats of our pants, even though we still have a long way to go.

All through these disruptions and re-adjustments, institutions, teachers and students have tried to bring in a sense of continuity through a collective unspoken ‘everything is normal’ attitude. We may say that these are unusual times but we continue to make demands on ourselves and others that don’t take cognisance of these unusual times. I am guilty of the same to some degree with my students and I know this will happen again. Situational awareness of limitations imposed by the pandemic needs to be translated into application and practice, which also means that we need to re-look at our propagation of a productive and always engaged worker, which include students. Interaction, human contact, the experiential aspects and on-site teaching create interactive spaces for engagement which are essential for the learning-teaching processes. This also means that we need to re-imagine our assessments and tasks for the students. However, it is going to take a long time before classroom teaching resumes its preferred mode of face-to-face engagement, and when we do, we cannot revert to our old comfort zones of old assessments, pedagogies, teaching subjects in silos with lack of emphasis on development of skills. Universities with liberal arts focus need to include skill development among the students which will make them sustainable without abandoning their liberal arts education.

Many universities and institutions are testing ways in which they could return to teaching keeping in mind the restrictions imposed by Covid 19. For example, a model where there are three lectures a week with all the tutorials and practical taking place remotely. Many private universities have the advantage of incorporating remote learning in a more systemic and innovative manner. For example, Ashoka University (Haryana) has initiated this through its platform AshokaX: An online learning experience, which offers ‘unique live classroom experience…[with] faculty switching between lecturing, answering questions and facilitating discussions….’ (a replication of face-to-face mode but in an online avatar) and personalised pathways. The courses are curated from across the world, open to all and are designed with varying duration and varying course fee structures. To read these is a dream for any student and faculty. But then this also brings to the fore the economic divide in addition to the digital divide. On the other hand, AshokaX is also reaching out beyond university going candidates. While this is not necessarily a negative thing and is certainly ‘inclusive’ as mentioned in the brochure, this isn’t how ‘inclusive’ education is generally conceived of as.

Prof John V. Orth from University of North Carolina

Thus far, I have mainly focused on teaching and learning in the time of corona. Recently I have come across references to asynchronous teaching and its effectiveness as it takes cognisance of the limitations of time-tabled virtual learning-teaching imposed on the students and faculty. In fact, it is one of the reasons why I too like the online courses offered by edX and similar platforms as I can pace my own learning process even though the duration of the courses are fixed. Maybe it is time for faculty to adopt certain features from these platforms. It is evident that we need to incorporate the 21st century skills that broadly fall under the three categories of literacy, learning and life, which we often tout about, into our very own course design. We cannot expect our students to have 21st Century skills without adapting them ourselves. Covid 19 has in fact rudely revealed that most teaching faculty have not themselves adopted these very skills.

There has been little mention of our struggles with assessments, based on which we assess students’ knowledge, which in many ways also reflect our pedagogies and methodologies. These I will explore in my next blog post.