Storytelling is not a tradition in Kashmir. The way we communicate is through stories

Kashmir has many stories of its own to tell beyond the visible political ones, though these have not been brought to the forefront because of the way New Delhi has treated place and its inhabitants over the decades.

— Onaiza Drabu, "The Legend of Himal and Nagrai and Other Stories"

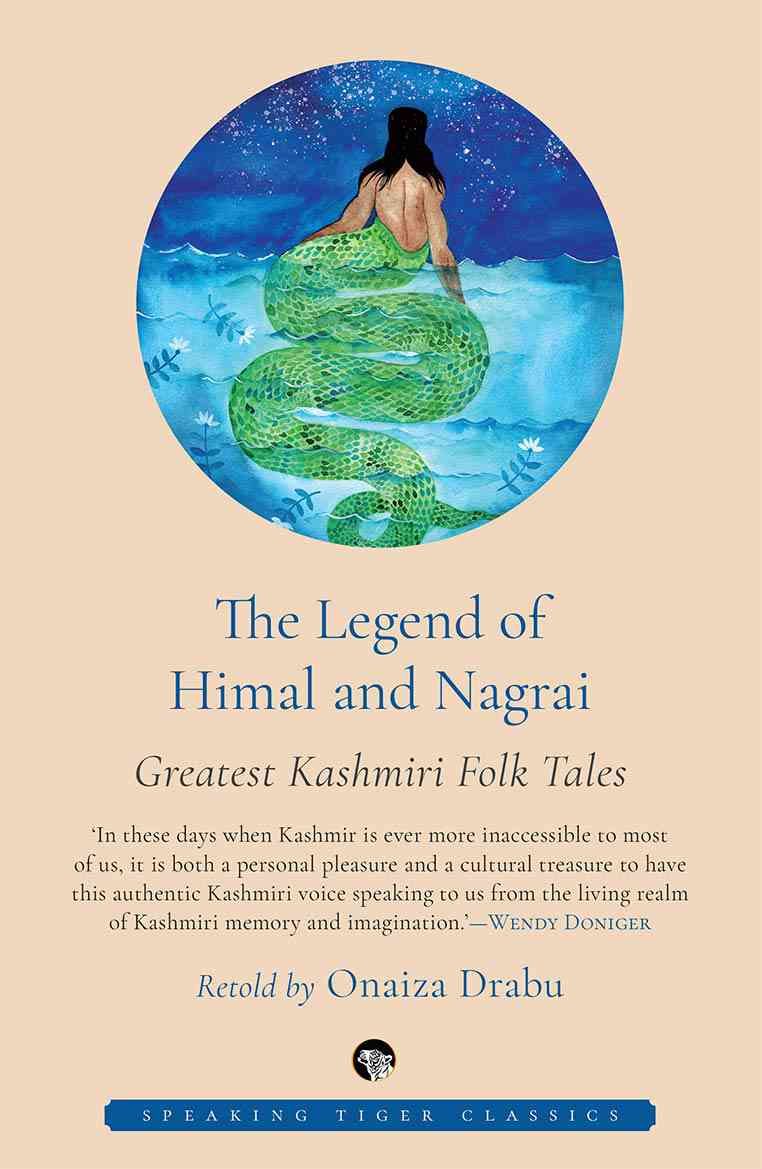

Onaiza Drabu, is an anthropologist, who graduated from Oxford University and whose research focuses on identity and nationalism in Kashmir. In her recently published book The Legend of Himal and Nagrai, she re-tells the folktales from Kashmir.

The following excerpts have been reproduced from an interview by Gokul S Prabhu for scroll.in. Drabu talks about the method of collecting these folktales, choosing the voice in re-telling of these folktales and reflections on the tradition of storytelling.

We invite the readers to share their thoughts on the interview and over nuances of storytelling and choosing the voice in the process.

We are who we are through the stories we are told and the stories we tell. I would be curious then, to know what our stories say about us Kashmiris. Kashmiri folklore tells us that as a race, we enjoy the macabre; that evil sometimes triumphs; that men need to be afraid of beautiful women who may lure them to a brutal end; that women must constantly be keep on vigil against ogres; that luck is vital and pretty much nothing can change if you’re destined for misfortune. We Kashmiris love our stories. Cut off from the rest of the world, in this multicultural, multilingual potpourri of customs and traditions,; we have spun our own yarns to live by.

How did you come to embark on a project like this one?

So back in 2014, I had started a project that looked at the aspects of Kashmiri history, heritage and folklore. I did a bunch of research on the heritage trails of different religious spaces in Kashmir, different devotional spaces and monuments, etc because a lot of that wasn’t happening. I also started a blog[1] that illustrated Kashmir proverbs and quirks in the language. What I was doing that time was researching Kashmiri poetry, Kashmiri language, Kashmiri folklore.

Kashmiri folklore has been very close to my heart for a really long time, it’s something I really associate with my childhood. I make this distinction between folktales and folklore in the introduction, where I am saying that everything about folklore is intertwined with a very superstitious core, which I find very intriguing. It’s something I use in my everyday.

It got formalised in 2017 in a conversation with my editor who encouraged me to do something about it, and that is when I started my research. I spent about six months researching in Kashmir’s libraries, where there are, especially in Srinagar, fantastic collections and incredible resources on folklore, folk songs and traditions – all in Kashmiri. So there’s this whole repository of resources that you have access to that are in Kashmiri or done by Kashmiris, but then there are barriers that make it hard. Most of these are out of print – only some copies are available in libraries. Others lie with the authors in their homes, given the limited print and distribution – so to access them there are many hoops to jump through.

I spoke to some older academics, and writers who would remember, people in the cultural academy, and other traditional storytellers about folklore, and spent a lot of time getting stories from them. At first, they would question the purpose of the project, but would eventually open up and start telling me about their stories and their lives, and they would just not stop. It was fun and interesting.

There are about a hundred and fifty stories, from many different sources and in many different voices, so when I do a retelling, I try to keep the voice of the original, so it’s not really my voice. But it’s also my voice. Do you know what I mean? I divorce myself from translating because when I translate, I would need to be true to the voice of the teller, but because it’s a retelling, I can play around with it just as the someone telling it had played around with it before it came to me. Essentially, these aren’t my stories. I am retelling other peoples’ stories – my people’s collective stories so finding the space to assert my agency was a bit of a struggle.

You say that Kashmiri identity is constructed by the stories they tell. Tell us more.

Yes, that is something I thought was very interesting because did you know, they say the Panchatantra is supposed to have originated here in Kashmir? Our stories have similarities and then also with the Persian storytelling traditions, those daastans are commonly heard. When traditional tellers tell these stories, like this one woodcutter who has helped me with a lot of stories in the book, they don’t know about these different influences. For them it all exists in this one coherent world, one syncretic realm of Kashmiri lore, this mishmash of worlds and traditions. They wouldn’t know that a Persian storyteller’s characters wouldn’t talk about nagas; it’s hard to explain to them that these realms are different.

Many tellers are unable to discern the many worlds of tradition – for them, these colliding worlds exist in harmony. The Kashmir of our storytellers is therefore diverse. The peris of Persian folklore live in harmony with the nagas of Sanskrit stories. Retellings of Persian daastans and the Sanskritic Panchatantra stories take place in the same setting – the glorious valley of Kashmir.

One such teller insisted I hear his favourite story – a Kashmiri love story, Laila Majnoon. As I laughed and tried to explain to him that it was not really a Kashmiri story he looked at me like one would a child who has much to learn. The man, who had had no formal education, sat me down to explain the strict characterisation and typology of people and stories in Kashmiri folklore. He sketched out the hidden realms for me and all the creatures within. Little did he know that he had combined characters and stories from many traditions, in a glorious mishmash that for him was Kashmir.

One reason could be that these stories are told and retold and usually by people who have not investigated it academically, who probably don’t even know how to read and write, and everything just blends. When people tell you this story very casually, they don’t realise how they are bringing in all these different traditions. I think I have picked up on all these different sensibilities, traditions, voices, and what I have done, I think, is picked up from these multiple people who are Kashmiri, whose identities are Kashmiri and retold their stories as authentically as I can.

There were moments where I was very hesitant – some of the stories really bothered me, because they are problematic in their own different ways. I would never want to retell some of these stories because with every retelling there’s a sense of responsibility. Should we not be retelling stories the way we want them to be remembered?

When I grappled with these questions, I also thought of the aim of this project, which is to ensure that all these voices exist – there is misogyny, there is inequality, all of this must exist. There’s much to be problematised in Kashmir and I didn’t want to twist it to make it something that is my idealised version of the place. So I just told them as authentically as I can.

I know there will be a time for me where I will be able to reimagine, reinterpret all of these stories but that’s not now. Right now, it is responding to the need of preservation, and of documentation. It is responding to the need of creating an accessible repository, and manifesting these stories from storytellers who are hidden from our very digital, very globalised everyday.

Few tell these stories anymore. These stories are gathering dust in public libraries somewhere in Kashmir and no one is reading them. I hate to say this, but it is also to serve as a reminder that Kashmir is more than what you hear – there’s violence, there’s unrest, and it is beautiful, yes. But there is also so much more.

In the dominant narrative, there’s also the fetishisation of Kashmir in most of India – there is an element of viewing it as exotic without much active engagement. In reality though, Kashmir has a very rich tradition of poetry, of mysticism, the language holds so many treasures, and I’ve tried to incorporate much of this in the stories. That is the Kashmiri identity I am talking about.

The foundation of this book lies in the act of storytelling. How important is this act to a space like Kashmir?

If you ask people about the tradition of storytelling, they will not know what you are talking about. There is no tradition, really, we don’t remember stories. But then the way we talk, the way we communicate is all in stories. I wanted to call this book Dapaan, which is the word for “it is said”; you’ll see it invoked throughout the book. Every story starts with dapaan, which is an important element in everyday speech in Kashmiri, it’s nothing to do with storytelling, it is the way to begin any story, fact, or myth. Fact takes a backseat when dapaan is invoked.

I recently wrote a piece[2] where I documented all that I overheard during the communication clampdown in August. It talks about how history in Kashmir is not of the state because the state narrative is very different from what we see around us. So, the word dapaan becomes very important in the way we talk every day and it’s also an important element of storytelling because all stories start with it.

It invokes a really, really big sentiment of rumour, hearsay, but also conversations. Orality is a big component in Kashmiri or Koshur, the language. It’s not a distinct form of theatre or performance, what I am talking of, but present in the everyday amongst groups of people who spend months, most often all of winter, holed up making handicrafts. And while that happens someone there will sing a song or tell a story.

So storytelling forms a very big part of the everyday without it being consciously a part. People don’t go to watch storytelling performances. People have people and know people who come home and tell stories. Storytelling and raconteuring are techniques of expression – conversational skills here – that people recall and admire, but very unconsciously.

What were some of the challenges you faced as you worked on this project?

I think the first challenge I really faced is apathy. A lot of people don’t think that much of this is valuable anymore. When I started collecting literature I went over to this place called the Kitab Ghar – which I think is a government run bookstore for the Jammu Kashmir Cultural Academy publications – and told them that I was looking for some volumes. Their response was shocking; they said it had been destroyed in the floods, and they did not even have a master copy.

I thought they were joking, but they really weren’t. I had to chase one of the authors of these editions, who thankfully had his copy. For another set, I had to contact this bureaucrat who allegedly hoards these books, but when I tried to reach them, I was told that they were away for the winter, and the copies he had were a limited edition. It’s so hard when people who have access to them are not even using them!

However, there are a lot of private libraries that have them, and a lot of these and even the public libraries were extremely nice to me, and opened their doors. This one time, it was a very cold winter day and I was trying to scan some pages, and this government library offered to let me take the books home; while it was a nice gesture, the apathy bothered me a little. I definitely did not want to risk anything, especially given that one of the books I was working with was the last copy that I had tracked down.

The second challenge was the access I had to these spaces as a woman, which would definitely be easier as a man given that Kashmir, like all societies, is patriarchal. Lots of people did not want to talk to me because I am a woman, and many that I approached to even ask for directions, would not speak to me without commenting on how my dupatta should be a certain way.

Women are out and about on the streets and have a lot of agency, but there’s always a line that you can’t cross, and I found this extremely hard to grapple with and negotiate. But what helped was that so many people have created such fantastic resources online; there’s a lot of people doing a lot of work in preservation and I’ve mentioned a few of them in my acknowledgements, but these really, really helped me get access to so much material. How Kashmiris are archiving their culture digitally is phenomenal.

You have talked about something Ghulam Nabi Aatash said to you, “every time a tale is told and retold by [you], [your] zaath (lineage), [your] person, is added to it.”

I was very nervous when I started, but felt better when I was collecting the stories. However, when I sat down to write and compile everything, I panicked. The stories were everywhere – on my recorder, in pdfs and in notebooks. I panicked slightly because I was not sure how to standardise my translations and my voice, and when I tried, what came out did not make any sense to me. It was not what I wanted.

But the minute I actually had that conversation where I reckoned with myself that my role was not that of a storyteller, but of a curator, someone who is looking at this big bookshelf of books that haven’t been read in forever and choosing which ones to take out and read to someone else. As I changed focus from creator to curator, it became much easier to assert myself and choose stories and create a narrative.

Then I put the dictionary together once the narrative took place, and it is in this dictionary and the last story, which is titled “Soda Byor, Boda Byor” where I asserted my creative agency. I had the whole book lead up to this last story and the dictionary, and everything else, I was only curating. So that is where my “I” really came into being. With the other stories, I have made multiple drafts to make sure that the teller’s voice is maintained.

Something very unique about The Legend of Himal and Nagrai is this dictionary, the Dictionary of Imponderabilia, at the end. Why do you think it is significant, and how did you put it together?

The dictionary was one of those things that I did not intend to do, but as I was writing and translating, I realised that there was a lot in terms of the vocabulary inherent to these stories I did not want to change – a lot of them represented ethos, or beliefs, and were best expressed in Kashmiri. Those were sentiments that were untranslatable into English. I was already working on a list of such words for something else, so I expanded that list.

But as more of these words came up in the stories, I realised that these were not just words but also a representative of the culture I wanted to talk about in the book. The anthropologist Malinowski talks about the “imponderabilia of everyday life”, while advocating for immersive ethnographic research into a culture. This is what I picked up on and used to make this into a Dictionary of Kashiri Imponderabilia.

For me these are very core, essential elements of being Kashmiri, speaking Kashmiri, living in Kashmir, and living in a Kashmiri culture. It isn’t something I’ve made up, but merely documented with a lot of help from everyone around me. I’ve spoken to many people about it, shown it to many people and they’ve suggested more words. So this build-up has been very organic – not comprehensive at all. But it’s just been built up from the stories, from people I know, from things I see.

Why do you write in English, especially as you deal with stories and folklore that are local to your vernacular language?

It’s a post colonial heritage that my native language is English; it’s the one I’m most comfortable in. I actually learnt how to read and write Kashmiri through this process of collecting folk stories and folklore. During the research process, I had someone to help me read the stories because while I could read Kashmiri, it wasn’t really so easy. I was painfully slow. I was looking for someone who’d read for me and I’d probably record and ask questions if I get stuck, just to make the process a bit faster.

When I did hire someone, he actually thought reading to me was pointless, so he started teaching me how to read alongside him reading for me. So, I learnt how to read and write Kashmiri in the whole process of collecting and retelling folklore, but in another language. And when I read it, I would start thinking in the language I was most comfortable in, which is English, but it just gave me something I never had.

I never learnt Kashmiri in school, never learnt in the curriculum when I was growing up here in Kashmir. It only recently became part of the curriculum, and also because most people of our generation wouldn’t pick up a book in Kashmiri. It’s just a sad reality that even if people here would pick up an old book, they very rarely pick up something that’s actually written in Kashmiri. The script is hard, and parents prioritise, and rightly so, their readiness for a global market. So, I guess, that’s why the retelling is in English – I do it in the language I am most comfortable in.

It is an interesting question given that my relationship with my mother tongue, which is such a part of my identity, is mediocre at best.

What will your advice be to those who pick up projects of preservation, especially in times like these with a pandemic crippling us?

It is interesting that you ask this. My day job is to help organisations transform themselves digitally, and with what is happening with the pandemic, we are indefinitely suspended with digital being the only mode of communication available to us. This is probably a great time for those who seek to work in projects of preservation, mainly because it gives us time and space to reflect on the ethos behind what we want to do – the what and the how.

Digital is especially useful if we come at it from a public good motive, which is creating spaces that are open, accessible and free. My advice would be to ask questions of what it is that we want to preserve, how is it that we want to reinvent, or curate it, and then take active steps towards the end product. Thinking through the motivation also is important – it also is essential to keep us going in these anxious times – to circle back to the question of why our work has any relevance.

Lastly if it is stories, and oral history or folklore, I’d say listen. There is so much hidden in plain view in the language of expression that the closer you listen, the more you pick up the imponderabilia.

To visit the original source: https://scroll.in/article/959465/storytelling-is-not-a-tradition-in-kashmir-the-way-we-communicate-is-through-stories

[1] https://onaizad.wordpress.com/

[2] Overheard in Curfew. 25 August 2019. https://onaizad.wordpress.com/2019/08/25/overheard-in-curfew/?fbclid=IwAR10CbZcEbNQfHYOODRmaq_NlgbjW19TwMciJ6aafgm653qf9HNpjQX1SIY