Rarely has a plant held so a central position in as many civilisations as the Indigofera species. In West Africa, indigo is by far the most important vegetal dye. It plays a key role in different traditional cultures.

Underestimating the diversity

The generic labelling of Mali as a vast desert landmass belies the enormous disparity between its geographical regions – from the arid Saharan zone shared with Mauritania, Algeria, and Niger to the forests on the borders with Côte d’Ivoire and Guinea. This erroneous representation makes it difficult to see rich ecosystems anticipate the threat of further degradation or even extinction of extant species.

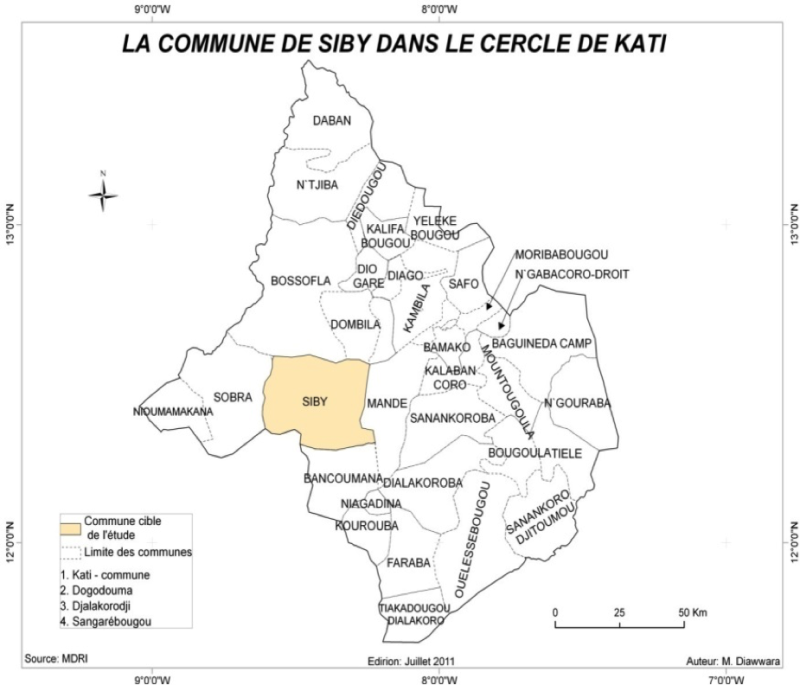

The rural commune of Siby is located at about 45 km south of Bamako and at 75 km from the border with Guinea. In the heart of the hilly Monts Mandingues, Siby is rapidly becoming a popular tourist destination for the succession of spectacular landscape formations its area harbors. The legendary arch in the nearby mountain is associated with the decisive medieval battle at the foundation of Old Mali. Beyond its protected forests, the area has experienced rapid growth in cross-border travel, tourism – especially brisk since the security crisis in traditional hotbeds like central and northern Mali – and boom in agribusiness since the early 2000s. Many affluent residents of Bamako have invested in modern farms and secondary housing in and around Siby.

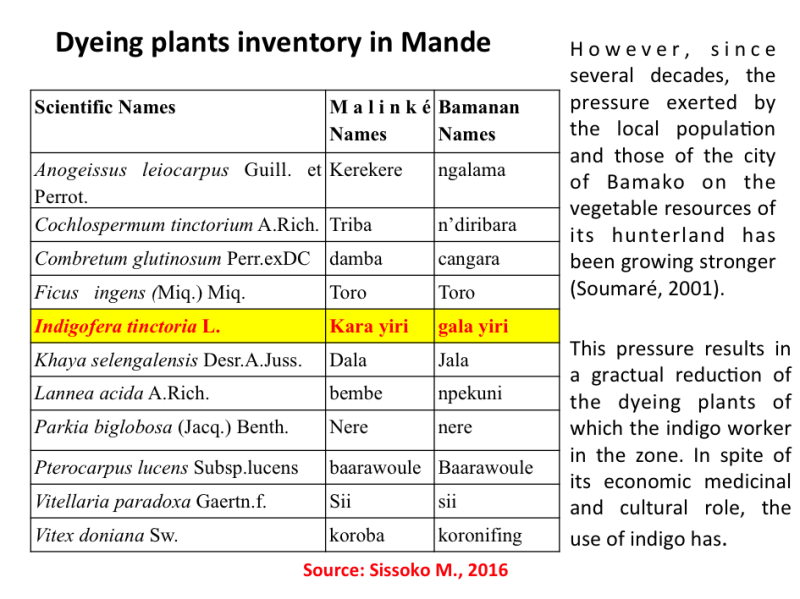

All these factors, from internationally sponsored preservation to touristic and entrepreneurial incursions, have put the forest resources of the region at the centre of concerns. Here the focus is on the degradation of dye plants in general and the indigo tree in particular in the rural commune of Siby in southern Mali. Indigo dyeing is not only an ancestral craft, but also a practice with spaces of vocational or professional training developed over time and across multiple traditions. In this regard, the preservation of endangered plant species is dependent on the ability to care for fragile ecosystems.

Siby is located at about 45 km south west of Bamako on vital road to the Guinean border (RN5). Proximity with the fastest growing capital in Africa for over a decade subjects the area to drastic urbanistic and industrial pressures - quasi-suburban housing, land purchase, traffic-related noise and pollution.

Recurrent threats to natural resources

The rich and varied plant heritage of Mali is unfortunately threatened with extinction mainly as a result of unsustainable human exploitation: deforestation, overgrazing, anarchic logging, poaching, bush fires, and climatic hazards like rainfall deficits. The historic droughts of the years 1972-1973 and 1984-1985 reshaped considerably the landscape all over the Sahel, transforming a forest region into savannah or grassland into a sandy plain. Its impact raised national awareness about the fragility of the surviving and recovering ecosystems; yet political action continually falls short of meeting the minimum effort require to maintain a durable balance. Useful plants like the indigo tree are not necessarily spared since the whole environment is changing and the conditions for its existence may no longer be in place in many areas.

The whole cycle of production is dependent on and vulnerable to climactic changes that have deteriorated considerably over the last three decades, under the pressure of rampant urbanisation and agribusiness ventures. Consequently, the picturesque hilly Siby region, in the vicinity of Bamako, the fastest growing capital city in Africa according to recent statistics, is prey to all sorts of land speculation, landscape fragmentation, and durable destabilization of fragile ecosystems. The indigo tree is thus threatened in its existence, so are the crafts and other livelihood practices associated with it.

Indigo: practices in traditional and ancestral dyeing in Mali

The indigo plant is a herbaceous or shrubby plant, woody at the base with alternate compound leaves. It grows mainly in the vicinity of the villages. In a spontaneous or cultivated way, the indigo tree grows in rather steep and sunny areas with optimal temperatures. It is not very demanding in terms of soils. It thrives in permeable soils that are rich in organic matter with a pH between 5 and 7,3. Indigo tinctoria does not do well in heavy rains and soaked soils.

The use of vegetal dye is an old tradition that has accompanied the evolution of humanity. From Africa to Asia, via Europe and America, it has been an important part of the cultural and economic history of different peoples. The leafy twigs, the Indigofera tinctoria, and some species close to Indigofera, are the main sources of indigo dye, which have been used since ancient times to dye textiles in blue. In West Africa, its sphere of influence encompasses the past of present-day Mali, including southern Guinea and northern Côte d’Ivoire. In this vast area, a single Mande word is used to designate indigo: gara or gala.

Historically, there had been a form of specialisation among certain ethnic groups, as the Soninke prepared and dyed with indigo while wool weaving – including tapestry – remained the preserve of the Fulani of the Massina (Macina). In West Africa, indigo dyeing is a cultural maker in the first place, but it also illustrates the transfer of craft practices and techniques across the region. Indeed Soninke traders apparently brought it to Dogon villages, where indigo dyeing would become a strong and well-defined tradition of its own. The practice would move to the border area between the Dogon country and today’s northern Burkina Faso. In one remarkable development, Songhay-speaking farmers from the same area moved among the Moose (Mossi) after the fall of the Songhay state in the late sixteenth century. They adopted indigo cultivation and dyeing, and this craft has come to define their identity – Maranse – to date. In a word, indigo transformed the Songhay into Maranse in the Moogo (Moose country). They developed it into a specialty they, which they later passed on to Moose and other communities. (See the case of such transfer of know-how and work site in the villages of Nakamtenga and Youba in northern Burkina Faso)

In practice, because of its attractive deep blue colour or light and the wide range of colours that are obtained by combining it with other natural dyes, indigo has been described as the queen of tints. Rarely has a plant held so a central position in as many civilisations as the Indigofera species. In West Africa, indigo is by far the most important vegetal dye. It plays a key role in different traditional cultures. In areas far removed from its heartland, people are ready to spend a fortune on indigo-dyed attire(s) and accessories. This is particularly true of the Tuareg in the Saharan and Sahelian regions (Niger, Mali) with expensive, richly dyed turbans for men and saris for men. It is also true for the Soninke (also called Sarakole or Marka by other groups), especially the women in the area of Djenne in central Mali. Even the Fulani, who were more oriented toward wool, use dyed clothes to complete the ceremonial clothing of brides and grooms during weddings. Interestingly they would entrust this part to the Soninke women of the community.

Dye extraction

The leaves and twigs do not contain indigo; they are colourless precursors from which, once processed, dye can be extracted. The dye, derived from the leaves of the indigo plant, has a particular feature: the coloration of the fibre is not visible on impregnation but at the exit, through oxidation. Indigo is reduced to an invisible body and resumes its blue form during oxidation. This plant has hence become a key element of West African cultural heritage. As a matter of fact, the two classic colours in West African textile culture are white and indigo.

Spaces for the professionalisation of the practice of indigo in evolution

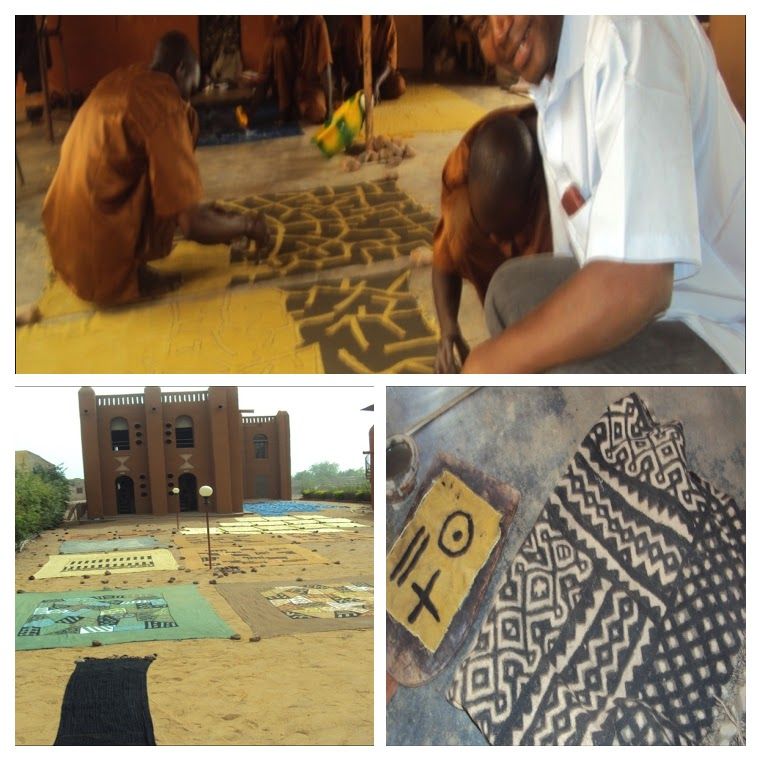

Artisanal dyers form economic organisations, which transmit an intergenerational knowledge base. The work of indigo, like that of any other dye plant, underlies a production method inbred in local traditional textile crafts. As such, the dyeing cycle traditionally enables young craftsmen to enter apprenticeships in workshops, learn from established practitioners, start their own practices, and later transmit their mastery and personal recipes to other apprentices. They also learn or adopt a business model to accommodate the latest fashion, respond to the needs of the market, and resist both change and decline. The profession, know-how and craftsmanship are thus transmitted from generation to generation.

(a) Dyeing of bogolan clothes in Ségou. (b) Drying the cloth after colouration. (c) Bogolan cloth

Selected References

Ag Sidiyene, Ehya (1996). Des arbres et des arbustes spontanés de l’Adrar des Iforas (Mali): étude ethnolinguistique et ethnobotanique. Paris: Orstom; Montpellier: Cirad.

Diarra, Balla et al. (2003). Structure urbaine et dynamiques spatiales à Bamako (Mali). Bamako: Editions Donniya.

Duponchel, Pauline (2004). Textiles bògòlan du Mali. Neuchâtel: Musée d’ethnographie.

Gardi, Bernhard, ed. (2003). Textiles du Mali. Bamako: Musée national du Mali.

Lalinon Gbado, Béatrice et al. (2006). Les messages du pagne. Cotonou: Ruisseaux d’Afrique.

Sissoko M. (2016). The tinctorical plants of the rural commune of Siby and their use for the preparation of natural dyes. Doctoral Thesis (Ethnobotanics). University of Bamako.