For several decades, media literacy has been understood as the critical reading of mass media and its educational possibilities. However, the rapid diffusion of digital technologies has changed the media landscape and it is almost time for us to fundamentally re-examine the terms ‘media’ and ‘literacy’. In this essay, I first provide a short overview of the current situation of media literacy in Japan. Second, I examine digital storytelling (DST) practices and discuss DST as one new method for achieving media literacy in Japan.

Challenges of media literacy in Japan

Japan is one of the most media-saturated countries in the world. Although a consistent national curriculum in media literacy, such as that offered in the U.K. or Canada, has not yet been introduced, compulsory and higher education involve systematic programs on media and information. In my personal experience, most of today’s Japanese undergraduate students exhibit at least the textbook definition of media literacy.

Media literacy has been understood for several decades as the critical reading of mass media and its related educational possibilities. “Look carefully, think critically” was the catchphrase. In the late 1990s and into the early 2000s, I revised the definition of media literacy in several ways, because the emergence of digital media was turning the general public from being just readers and consumers into writers and creators.1 One revised definition presents media literacy as a synthesis of three communication activities: technological operation, critical reception, and active expression. These three elements should complement one another; media literacy cannot proceed properly if the balance between them is lost. This provides a more comprehensive understanding than the traditional definition, which focused only on critical reception of media texts, and it has become a standard in understanding media literacy today. However, the rapid spread of digital media such as smartphones and SNS (Social Networking Services; examples include sites such as facebook and twitter), paired with the conservative Shinzo Abe administration, has changed the Japanese media landscape once again. It is almost time for yet another fundamental re-examination of the terms ‘media’ and ‘literacy’.

In reviewing the recent media landscape of Japan, three issues cannot be overlooked. First, the Shinzo Abe administration has openly suppressed freedom of speech and journalism in Japanese mass media. Over the past few years, the Abe administration has attacked mass media on various fronts, from introducing right-wing Abe supporters into the management board of public broadcaster NHK, to threatening to revoke the broadcasting licenses of those stations that produce news programs critical of the Abe administration. These troubling occurrences have been, worryingly, accompanied by critical comments on SNS by the general public, who welcomes these changes. The Japanese general public has mixed feelings about mass media; people are attracted by the aesthetically pleasing possibilities of the media, yet appalled by their superficial activities. Many misgivings with regard to mass media journalism arose on SNS, for example, after false reports and misinformation about the 3.11 disaster and the subsequent Fukushima nuclear power plant meltdown. Those suspicions, as a result, became linked to the Abe administration’s suppression of mass media. Nowadays, mass media journalism wavers between the suppression of authority and criticisms of the general public.

Second, the era in which mass media alone was responsible for producing national master narratives came to an end around the time that the Internet became widely prevalent in the 1990s. The optimistic dream of rich and diverse free speech born on the net began to spread. However, as smartphones and SNS become ever more commonplace in the 2010s, and with the master narratives of mass media no longer available, extreme and violent narratives are erupting onto the scene to replace them. Typically, these narratives are loud, racist and nationalist outcries from civilian groups, as well as unusually fierce criticism of the unscrupulous behavior of politicians and entertainers by the general public.

Third, a so-called ‘invisible illiteracy’ has emerged in Japan.2 In recent years, smartphone ownership in Japan has grown, whereas the number of PCs in use has declined sharply. Although this may simply reflect a public preference for newer, more convenient media, there are some undesirable side effects. On a smartphone’s small screen, only one application can be selected at a time; as people grow accustomed to performing only simple operations, the probability is high that they will no longer be able to engage in the more complex mental work of utilizing multiple windows across a wide range of software launched on a computer. The invisible illiteracy noted by Lim in studying the mobile communication habits of young people in Singapore has also become a reality, especially among younger people, in Japan. At present, the industrial world of Japan faces a problem with new employees hired straight out of college, who are lacking the technical abilities to operate computers. Ironically, people whose lives are in fact awash with digital media are at risk for this type of illiteracy.

The problem is that most of the people attacking journalism, espousing racism and nationalism on the Internet are media literate in active expression (and possibly technological operation), but clearly not in critical reception. Previously, I mentioned the mutual relationship and importance of a balance between the three elements of media literacy: technological operation, critical reception, and active expression. A lack of balance has occurred within the new media landscape.

Many media and communication studies have found that people are increasingly living in ‘island universes’. In the age of mass media, for example, newspapers and television programs managed to develop public communication spheres in which people could get a broad overview of the socially important agendas, and where they encountered different opinions. Within an island universe, people share the same opinions and lifestyles; they receive selective information, commentary and input from their favorite blogs or SNS groups. They don't look beyond their islands, towards other ‘cultures’. Even though people may be able to proficiently operate smartphones and SNS, and even though they can actively express their opinions, they are less and less able to critically receive information. Digital media users are increasingly incapable of critically examining social commentary. A new blueprint for media literacy is required; one which will suit a media landscape without mass media at its core.

Digital storytelling in Japan

The most popular path to reach media literacy is through school education. However, school education in Japan is generally highly institutionalized, and there is not much allowance for teachers to incorporate digital media into the classroom. In Japan, where schools are seen as pure learning communities, the administration is reluctant to introduce any kinds of popular media into the classrooms, even though music videos and popular films have proven to be quite good teaching materials for media literacy in Western countries. Regardless of these constraints, we need a new type of media literacy that is applicable not only in school education, but also in the whole of people’s everyday lives, because today’s digital technologies have been changing the whole of the media landscape. It is not possible to provide a complete discussion here, so I will focus on one possible direction we could take: digital storytelling activities.

Digital Storytelling (DST) is a grassroots movement and a workshop-based practice that allows people to create short video stories using personal computer-based files (images, video, audio, etc.). Topics primarily include personal histories or everyday matters of concern to the creators. Stories are created in first-person style and narratives are recorded using the creators’own voices. DST was initiated by artist Dana Atchley in San Fransisco, in the early 1990s, and further developed by the Center for DST in California. It has since spread throughout the world as a form of civic education, empowerment, and a source of public history. It has been integrated with diverse fields such as hyperlocal journalism, mental health, preschool education, among others. The videos are shared at screenings during community gatherings, through local cable TV stations, and via the websites of local institutions.3

I have been engaged with practical media studies’ projects such as Media Exprimo and Storyplacing since the mid-2000s. Media Exprimo is an interdisciplinary-design research and information platform that supports general people’s media expressions and digital storytelling.4 Storyplacing is a bilateral research project (Finland and Japan) with a transdisciplinary and international team specialized in media studies, information design, and community planning. The team has developed workshop programs and online platforms to encourage people’s storytelling, and put them into practice both in Finland and in Japan.5 My fellow research project members and I have been developing new types of digital storytelling to encourage media literacy in Japan. Since the mid-2000s, we have produced four DST programs that were formulated with the cultural context of Japan in mind, in which people face stringent peer pressure that discourages them from talking about themselves, and where as a result DST is not yet common or widespread. The programs are community-linked media projects intended to encourage general people to (re)weave collaborative storytelling networks via mobile media, such as smartphones or tablets, within local communities.

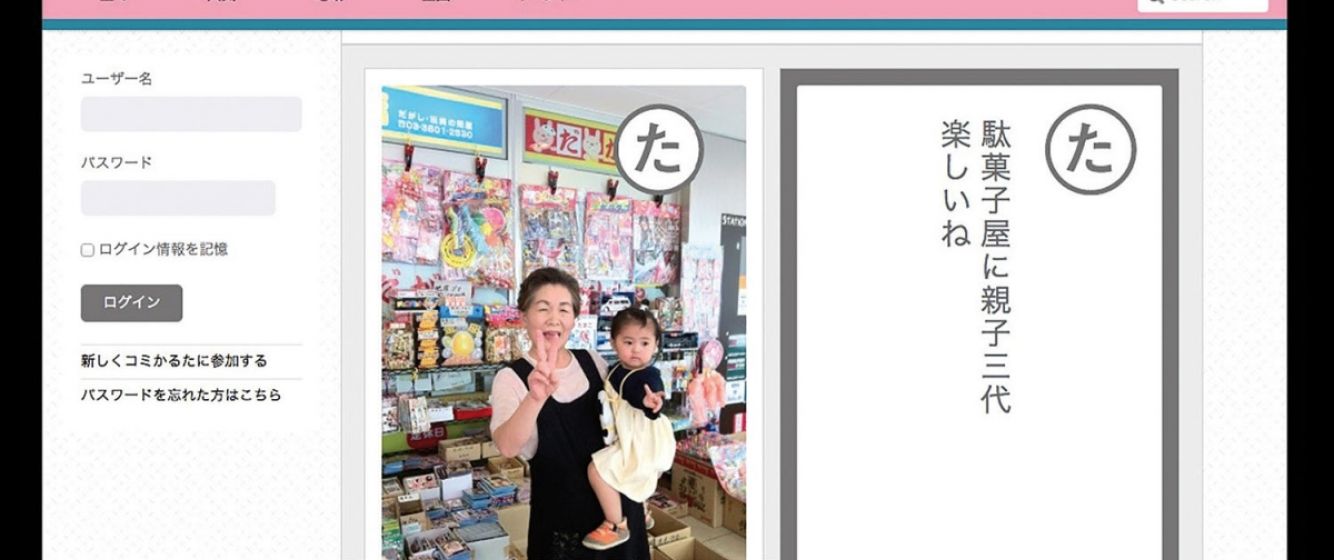

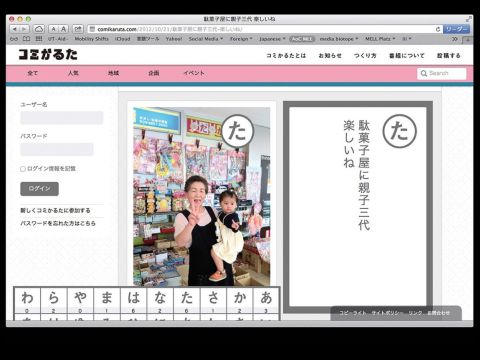

The four DST programs are the Comikaruta, the A-I-U-E-O Gabun, the Media Conte, and the Telephonoscope.6 The Comikaruta project is a communal card game; the A-I-U-E-O Gabun project involves acrostic poetry; the Media Conteproject is an interactive digital storytelling program with twenty to thirty photographs accompanied by people’s voices; and the Telephonoscope project is a micro-voice storytelling system using a black rotary telephone and an iPhone application.

To solicit the participation of different generations, the programs intentionally introduced forms of Japanese traditional cultural play, such as Karuta (a Japanese card game), haiku (a form of Japanese poetry), and A-I-U-E-O bun (an acrostic word game; gabun is a new term coined by us, consisting of ‘ga’: image, and ‘bun’: text). To sustain their impact, the DST programs were not only carried out as workshops at university campuses, but have also been deployed in local schools, among neighborhood municipal bodies, at traditional festivals, to local governments, and through cable television stations.7

Collaboration, playfulness and sustainability

The four programs above share three features: collaboration, playfulness and sustainability. In each type of DST, rather than crafting a story alone, participants interact with a facilitator or weave a story as a part of a group. In Western DST practices, the mantra ‘everyone has a story to tell’ is the basis for the primary activity: digitizing complete stories already created by participants. In Japan, however, there are few opportunities to study or practice speech communication in compulsory education programs, and people are not at all familiar with how to tell a story in a public space. Because of this, DST workshops in Japan have to start with a dialogue between facilitators and participants and cooperation among participants. This collaboration discovers people’s dormant ‘story seeds’ (such as pre-stories, small fragments of ideas and experiences, unvoiced complaints, or humor), and these are then brought together to weave a complete story. In particular, Media Conte places great emphasis on collaboration. This is the first conversational activity devised specifically with shy Japanese people in mind. Furthermore, regardless of nationality, people do not simply retell a story they have developed individually; this activity successfully presents the option of consistently producing one’s own alternative stories.8

Activities to bring out the ‘pre-stories’ or ‘story seeds’ and to develop them are also designed to be playful. Various elements including Japanese traditional card games, short poetry, and a black rotary telephone, are used to allow people to participate in the DST workshops without feeling uncomfortable or awkward; everyone is able to have fun playing games. By using these tools and activities, moments of both laughter and tears arise while people are enabled to work together on storytelling. For example, the Telephonoscope activity uses an iPad with pre-installed iOS apps, encouraging people to tell a story using the built-in microphone. However, rather than using the latest digital technology as is, the iOS app was paired with an old-fashioned black telephone. This invited laughter from participants and led to a well-made media art installation.9

Conducting DST workshops in communities is almost impossible without the cooperation of universities and media members. However, our DST programs are designed for relatively easy implementation, even by non-experts. Although we do need to take part the first time a workshop is held, thereafter the workshops can be facilitated and continuously conducted by members of local cable television stations, educational institutions, NPOs, and so forth. For example, A-I-U-E-O Gabun and Comikaruta have been used for a number of years by a cable TV program in Bunkyō Ward, Tokyo, and have helped the media to gather the stories of local residents.

DST to obtain media literacy

Admittedly, our trials of DST are not perfect. First, there is a discussion concerning the quality of pictures, plots, and editorial works of DST produced by the general public. However, I do not believe that public-produced DST must meet the same quality standards as mass media-produced content. The interactive DST workshops create stories out of the voiceless feelings and thoughts of people. Most topics involve people’s everyday lives, not political or artistic matters. However, when DST is generated in many places, archived in many communities, and networked with other DST projects online, versatile streams of alternative stories will be created, challenging the master narrative in Japan.

Toriumi has described the emergence of people’s media expressions in the digital age as ‘Digital Mingei’ (Digital Folk Art). Mingei, minshugeijyutu undo, was a Japanese art movement of the early 20th century that tried to bridge professional artists and everyday people, and to reconsider the beauty in everyday life.10 Although Mingei was profoundly connected with the European Arts and Crafts movement, and also with laborers’ circle movements after World War II, it has been almost forgotten in contemporary Japan and is considered to produce nothing more than tourist souvenirs. Toriumi reconsidered Mingei in the field of DST. Media Exprimo and Storyplacing are also based on the idea that DST could be a people’s folk art in the information-saturated but digitally-divided society.

Collaborative DST practices must be an important element of media literacy in the new age. Based on the evidence from our long term research projects, I propose that the community based DST workshops are the ideal sphere for media literacy, introducing new information technologies and accepting parts of traditional media literacy knowledge. Currently, DST makes the following two unique contributions to new media literacy.

First, the DST production process is a comprehensive media literacy experience. As mentioned previously, I coined a definition of media literacy involving the three communication activities of technological operation, critical reception and active expression. These three were suitable components in a mass media-drivensociety. However, to theorize new media literacy in the digital age, re-examination is essential. In the DST workshops, both participants and facilitators are involved in a variety of communications and therefore acquire comprehensive media literacy by following the example of others. In theoretical terms, the adjectives ‘technological’, ‘critical’ and ‘active’, and the nouns ‘operation’, ‘reception’ and ‘expression’ can freely interact during the workshops. For example, not only critical reception but critical operation and critical expression take place among participants and facilitators. These syncretic experiences seem more effective than traditional and individual educational programs on media literacy.

Second, DST produces certain mediated communities (media kyodotai) through the cyclical process of creation and reception. Mediated communities are not a priori entities, they are communities that are produced through communication activities such as using, watching, enjoying, consuming, exchanging, and chatting via media. In the future media landscape of Japan, we should intentionally design and build up relatively small-scale communities that are generated by community media. In the field of media and communication studies, it has been frequently mentioned that media creates and maintains communities and societies where people can communicate mutually and live together. DST is one of the concrete media practices for mediated communities. As James Carey and Benedict Anderson discuss, journalism of mass media and school text books have created ‘nation states’.11 A series of DSTs can make relatively small mediated communities tightly connected with geographic and cultural communities. For example, we have facilitated DST workshops in many venues of Bunkyō Ward, Tokyo. While people create their own DST pieces in interactive workshops, the neighborhoods enjoy receiving them at community screening events, on local cable TV programs, and also as web content of their local institutions. DST pieces, such as 'Digital Mingei', activate neighborhood conversations. Through those conversations, people can become more aware of the differences between unique DST stories and stereotypical narratives from the mass and digital media. This process, as a result, develops abilities to critically receive and express opinions about images and stories of Bunkyō Ward.

‘Mediated communities’ and ‘social communities’ are closely related. The DST-mediated communities could thus be incubation sites for the development of new media literacy. Although they are small, they may serve as people's gyrocompasses in the media-saturated society. Needless to say, the aforementioned suggestions apply both to Japan and in general. We need the tenacity to develop both individual DST programs and a network of DST-mediated communities with a broad focus.

Shin MIZUKOSHI, The Interfaculty Initiative in Information Studies, University of Tokyo ([email protected]). This essay was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) & the Academy of Finland (AF) joint research project “Co-Design of Digital Storytelling System with Geographic Information,” 2014-2016 (representatives: Shin Mizukoshi & Mikko Villi).