Living with and in the forest in northern Thailand Engaging Karen youth in participatory community research

In line with the HaB’s overall objectives to develop new pedagogical frameworks at both local and global levels, the CESD’s project not only opens insights into context-specific learning related to rice cultivation as both knowledge and practice, but also contributes to critical reflections on rice, its meaning and related practices, that transcend institutional, national and regional borders, e.g., in other Asian or African contexts.

By Chayan Vaddhanaphuti & Malee Sitthikriengkrai

With a population of 438,450 the Karen form the largest ethnic minority group in Thailand.[i] They can be divided into two major sub-groups, Karen Pwo and Karen Sgaw, or Pgaz K’nyau [human being].The Karen’s cultural life and production activities are deeply embedded in a spiritual and holistic worldview. The forest is not only perceived as the source of all life, but also a dwelling place for different spirits, and thus treated with great care and respect.

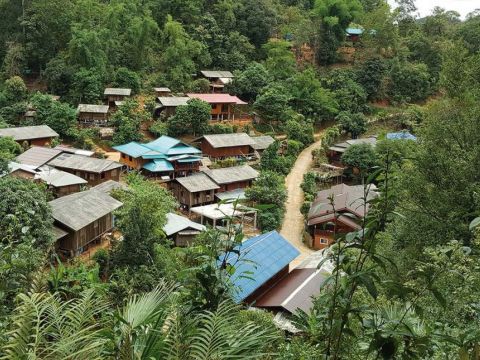

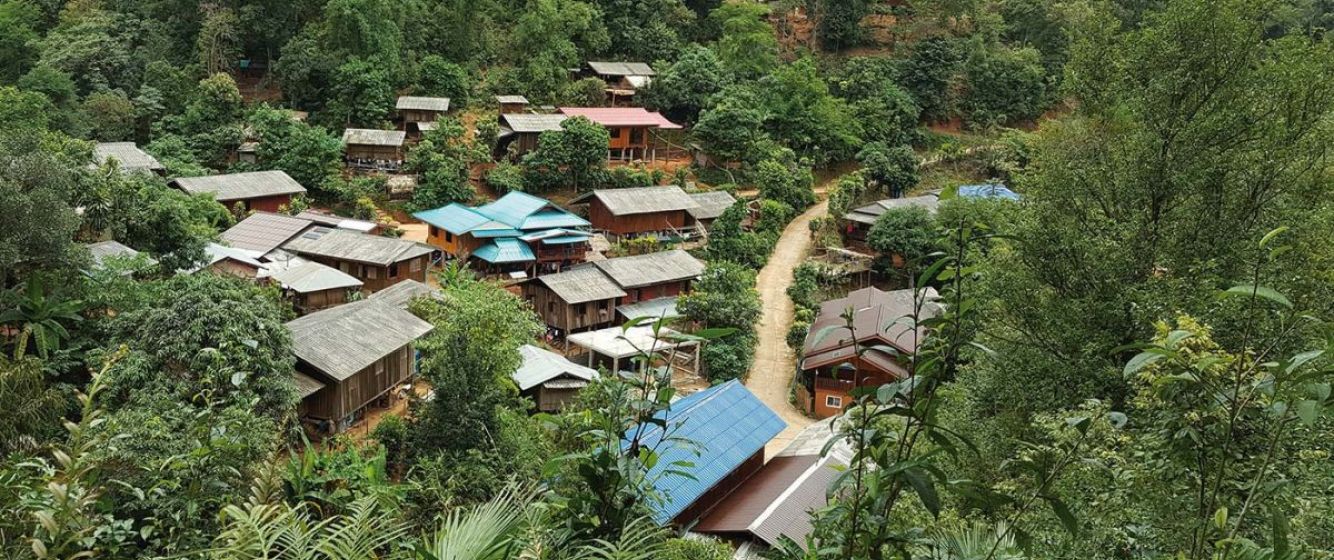

Huay Hin Lad Nai is a Karen Sgaw community located in a National Forest Reservation in Chiang Rai Province, Northern Thailand. With a population of 108 people or 21 households, this small community represents an example case for a sustainable and self-determined development approach. The villagers continue to practice traditional shifting cultivation [Rai Mun Vien], while government policies aimed at eradicating this form of agriculture have already forced other ethnic highland communities in Northern Thailand to replace hill rice farming with permanent cash crop cultivation.

The project ‘Living with and in the Forest in Northern Thailand’ of the Center for Ethnic Studies and Development (CESD), Chiang Mai University, Thailand, aims to enable the Karen youth of Huay Hin Lad Nai to study their own community history, their everyday knowledge and practices related to their life in the forest and to their traditional shifting cultivation practices, as well as the past struggles of the villagers for their right to live in the forest.

The CESD’s project is part of the Humanities across Borders programme (HaB), which looks to develop alternative pedagogies across disciplinary, institutional and national borders, with a focus on production sites of humanistic knowledge-practices in four regions of the world, Southeast Asia, South Asia, East Asia, and West Africa. As HaB’s local project partner in Southeast Asia, the CESD focuses on knowledge production in the Huay Hin Lad Nai community in Thailand in order to contribute to HaB’s larger vision of creating expanded humanities along the Asia-Africa axis of knowledge.

Empowering the ethnic youth

In order to understand the CESD’s approach of enabling learning processes among the youth as well as of strengthening the existing transgenerational transmission of knowledge in the community, it is crucial to look at Huay Hin Lad Nai as a community composed of three main generations, each with different experiences with the Karen way of life and with the outside world.

The first group, i.e., the generation from the age of 55 onwards, did not study in the formal education system. This generation has in-depth knowledge of nature, life in the forest and Karen culture. As ritual leaders and role models for the villagers, members of this group play an important role in determining the direction of today’s community development.

The second group includes villagers aged between 30 and 55 who have started attending the modern education system. During their childhood, they have witnessed threats through state-led policies and market pressure, e.g., the granting of forest concessions to private companies in the community forest. They have joined other ethnic groups, NGO workers and academics in a country-wide movement for environmental protection and land rights. This group had the opportunity to exchange experiences with other ethnic communities, especially related to community rights, and they learned how to negotiate with market and state policies.

The third group comprises the current community youth aged between 15 and 30 years, most of whom have attended school at least until elementary level. This generation deliberately chooses to stay in the community and practice shifting cultivation rather than to attend formal education and seek employment outside of the community. They have greater opportunities to interact with the outside society, and some of them have made training and study visits outside the village. They share a strong interest in actively learning about their own culture and in passing it on to subsequent generations.

The experiences of the first and second generations of Karen villagers differ greatly from those of the third generation, particularly with regard to their living in the forest and their interaction with community outsiders. For example, the young generation has never joined protest movements or negotiations with the government for the recognition of their rights. Instead, they have developed ways of earning income by selling different kinds of forest products.

Against this backdrop, the CESD’s project has identified the need of empowering and enabling the Karen youth to learn more about their own culture, community background and traditional agricultural practices from their fathers and grandfathers. Moreover, it seeks to create awareness among the youth for their own way of learning and to strengthen local knowledge and its production processes.

Pedagogy beyond classroom in key community domains

It is noteworthy that learning processes in the Huay Hin Lad Nai community take place in different social contexts, i.e., within the community, in the form of a transgenerational knowledge transfer between elders and the youth, as well as in the interactions and exchanges between community members and outsiders, such as other ethnic groups, NGOs and academics. In line with this, the CESD’s project is analyzing knowledge-practices related to a life in the forest and forest resource management that involve ‘beyond classroom’ learning of different generations, particularly in two major domains of the community: 1) learning through the everyday life practice of upland rice cultivation, and 2) learning to negotiate state policies through interactions with community outsiders.

Learning through the everyday life practice of upland rice cultivation

Even though it has been shown that Rai Mun Vien is able to ensure food security and to mitigate climate change impacts,[1] there is a wide-spread misunderstanding among forest officials and the wider public that this form of agriculture is a root cause for deforestation and environmental destruction. The Huay Hin Lad Nai shifting cultivation cycle follows a pattern of short-term cultivation and long fallow periods of 7 years. Besides rice, the Karen farmers cultivate more than 50 different kinds of vegetables in their rotational farms. The practice of Rai Mun Vien comprises diverse ritual performances led by the ritual leader, or Heekho, in which all community members participate. In some rituals, single young men and women play a particularly important role. Rai Mun Vienthus opens a space for Karen people of different ages and experiences to learn together in a community of practice.[2] This form of interaction gives different newcomers the opportunity to learn through interaction with old timers with diverse experiences. Accordingly, the youth of Huay Hin Lad Nai enjoy a learning process that cannot be separated from the formation of an identity that revolves around an intimate relation to nature.

In this context, a particular focus of the CESD’s project is laid on the learning of the third generation from the elders through the practice of hill rice cultivation, and on creating awareness among the youth for their own learning in the shifting cultivation cycle as an integral part of a life in the forest.

Learning through interactions with community outsiders

A second focus has been placed on the villagers’ learning to negotiate state policies through different measures, e.g., through joining movements and networks, and through engaging in research and community mapping. The traditional lifestyle of the Huay Hin Lad Nai villagers has been greatly threatened by development projects and state policies aimed at replacing their traditional shifting cultivation system with permanent crop cultivation. Moreover, the community faced a policy intent on evicting forest communities between 1993 and 1997, in line with the dominant conservation paradigm, which based on ‘Western’ ideas and concepts, emphasized the establishment of protected areas without human inference. Through this policy, the state sought to expand reservation forests in the country and to prohibit communities from living in these areas. Highlanders were labelled as non-Thai ‘hill-tribes’ who practice environmentally destructive slash-and-burn practices.

Even though the Huay Hin Lad Nai villagers have faced state power in various forms since 1983, they have been able to maintain their traditional rice production system until today, through a number of different actions and strategies. For example, the community has set-up networks with different forces in society to enhance bargaining power towards the state for the recognition of their community rights. In 1994, ethnic groups, academics and NGOs jointly drafted a Community Forestry Bill that differed from the Community Forest Act proposed by the Forest Department in 1989. Even though this Bill has not been passed, the movement created greater understanding among the youth back then (today’s 2nd generation) of their community rights and the need for action. NGOs and academics also began to support ethnic groups in conducting research and in producing proof that their community was living in the area prior to the announcement of protected areas. The villagers collaborated with NGOs and forest officials to produce maps depicting the land use of the community in order to demonstrate to the public that Rai Mun Vien is a form of local knowledge, different from slash and burn agriculture, as well as to show that their own communities are taking serious efforts to conserve their natural resources.

Through processes of interaction with outsiders and by joining protest movements, community members, particularly the 2nd generation, have thus acquired knowledge how to deal with threats to the Karen way of life, how to negotiate with government agencies, and how to maintain and defend their age-old shifting cultivation practices in the face of state repression, changing socio-economic landscapes and development pressure. Since the youngest generation has no direct experiences with the movement, the CESD’s project encourages them to learn from the older generations, and thus enables them to deal with development and state policies based on evidence-based research.

An unconventional approach to the co-production of knowledge

Accordingly, the CESD makes use of an empowering pedagogical approach that allows the ethnic youth not only to gain deeper insights in and learn about their own culture, ecology, and identity, but also to question mainstream development policies and programs. At the same time, it seeks to create a better understanding of how the youth comprehend their own learning from their parents and relatives. Rather than providing lecture- and text-based training in a conventional education setting, this project works directly with the Karen youth in the field and facilitates the co-production of knowledge between academics and community members through the following innovative methods:

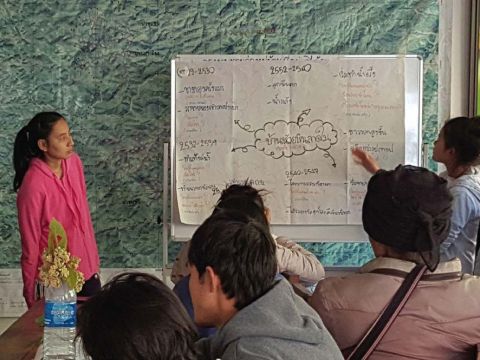

Studying local history. The project assists the ethnic youth to study their own community history, i.e., official historical records as well as the vernacular history of the community. The youth group has started to conduct in-depth interviews with community elders, particularly on the historical background of the community, family and kinship structures, the villagers’ local knowledge on natural resource use, and their encounters with state-policies. Supported by academics from CMU, they transcribed, edited and discussed the recorded material. In collaboration with visiting international students, they further recorded biographies of selected villagers and collected them in a booklet. First analyses of the collected data centered around community transformations and mobility patterns over the last one hundred years. Based on this information, a detailed kinship map and digitalized timeline of the community were produced. The latter highlights the close intertwining between community-internal events and the broader socio-political context.

Film Making. The young Karen were invited to produce a visual documentation of the Karen traditional forest life and resource management practices. In line with this, they have started co-producing a short documentary with international students in order to present their own narrative about Huay Hin Lad Nai to community outsiders.

Documenting Learning through Practice. Traditionally, the Huay Hin Lad Nai youth gain knowledge on community life in the forest and Rai Mun Vien through practice, learning by doing and on-site action engagement. For example, children learn about the rotational farming system and respect for nature through observation and engagement in parental activities. The shifting cultivation farm thus represents a socio-cultural sphere to transfer knowledge and cultural traditions and to foster transgenerational relationships. Also other sites of interaction serve as ground of learning in which young people acquire knowledge from community elders, e.g., ritual performances, such as funerals or the New Year ceremony. Thus, the CESD project teaches and encourages the Karen youth to observe, systematically document and reflect upon these practices.

Learning through Traditional Hta Verses. The Karen traditionally use oral and visual channels rather than written materials to transmit their knowledge. Besides their own experiences in the field, the youth also learn from sung or spoken traditional Hta verses, or quasi-sacred ‘word of the ancestors’.[3]Handed down through generations, Hta center around Karen values towards nature and society. They serve as culturally appropriate means of expression when a subject is of basic social importance or considered controversial. Accordingly, the CESD project also studies and records the use of traditional Hta verses in the community.

Exchanges with Other Communities. CESD is further facilitating exchanges with other ethnic communities in order to create greater understanding and awareness among the youth about the meaning and threats of mainstream development. For example, in September 2018, young Karen from Huay Hin Lad visited the Karen community Nong Tao in Northern Thailand, which has replaced shifting cultivation by cash crop production. Other than in Huay Hin Lad Nai, many of the young people work outside of the village, face problems with drug abuse and have little pride in their ethnic group. At the same time, the youth group of Ban Nong Tao has expressed the wish to revive traditional Karen culture in their community. Since the Huay Hin Lad youth have deliberately chosen to live and work with their parents in the community, they shared their experiences with their traditional lifestyle in the forest, and described their daily learning experiences in the forest and shifting cultivation farms: “Why should we be shy or not proud of our culture? When we stay at home, raise pigs and chicken and practice Rai Mun Vien, we are happy (…). If we go to school, our everyday life will be the same. We wake up early, have breakfast, sit in the classroom, do homework, and go to bed. This will be the same pattern from elementary to secondary school, and even beyond. If we stay at home, however, we learn a lot in different ways, and we are able to do many things”. The youth of Huay Hin Lad Nai highlighted that the visit in Nong Tao was of great importance for them to see and understand the rapid and profound socio-economic changes occurring in some ethnic communities, but also to reflect upon their own community situation and on ways how to prepare themselves to deal with such transformation processes.

Socially engaged research on rice cultivation in Asia and beyond

The CESD’s project makes use of a pedagogical approach that helps the ethnic youth learn about their own culture, knowledge, and their own way of learning. They are encouraged to reflect upon all-day life community practices in a systematic way in order to become aware of, reflect upon and strengthen existing knowledge-practices and their transmission processes. From the elders and their experiences, they are able to gain a deeper understanding of their own community context and of dealing with state polices. This can help them to defend their traditional lifestyle and knowledge against prevailing prejudices and misconceptions shared by government authorities and the wider public who continue to perceive hill rice cultivation as a backward agricultural practice and as a major cause for deforestation and environmental destruction.

In line with the HaB’s overall objectives to develop new pedagogical frameworks at both local and global levels, the CESD’s project not only opens insights into context-specific learning related to rice cultivation as both knowledge and practice, but also contributes to critical reflections on rice, its meaning and related practices, that transcend institutional, national and regional borders, e.g., in other Asian or African contexts.

Accordingly, at the 6th Conference of the Asian Borderlands Network, held in Bishkek from 13-15 August 2018, CESD researchers and other HaB members from South and Southeast Asia and West-Africa presented their research on rice and the creation of ‘rice-scapes’ through different modalities of rice cultivation in a double panel titled ‘Asian Rice-Scapes: Topographies, Tastes and Technologies’. The different papers analyzed interconnections and divisions between hill communities and lowland settlers and explored rice as knowledge-practice based on three different ecological systems – water based, lowland and upland rice – which coincide with different rice cultivation techniques, such as irrigated or rainfed, settled cultivation, as well as shifting cultivation, or the rotational use of land plots. Participants had the chance to jointly reflect upon the development of a rice syllabus based on these ecologies, by drawing on the presented local examples from different parts of the world. Comparisons across borders revealed the importance of the research process as a crucial element for the development of an alternative pedagogy of rice that allows unconventional approaches and perspectives and that can be reproduced in different geographical contexts.

Accordingly, the CESD’s project proposes a syllabus for an ethnic youth training on participatory research methods, which is highly relevant to create an in-depth understanding of local knowledge and learning processes, and which can equip villagers with the skills to maintain and preserve their traditional culture and ancestral cultivation practices against challenges through state policies and economic development pressure. This can be beneficial for other countries and regions, since local and traditional rice cultivation practices are facing growing pressure worldwide due to the impacts of climate change, the large scale expansion of urbanization, increasing monocultures as well as the shrinking of arable land.

Future transnational and regional collaboration of the rice project may center around further compromising process and content of different ecological and regional approaches in order to shape an alternative rice pedagogy that ultimately feeds into the development of an expanded ‘humanities across borders’ curriculum as an overall outcome of the HaB programme.

[1] Northern Development Foundation (NDF) & Huay Hin Lad Nai Community. 2011. Climate Change, Trees and Livelihood: A Case Study on the Carbon Footprint of a Karen Community in Northern Thailand. AIPP, NDF, IWGIA; Trakansuphakon, P. 2010. ‘Traditional Livelihoods, Food Security and Climate Change in Thailand’, in Asia Indigenous Peoples Pact Foundation (AIPP)Traditional Livelihoods and Indigenous Peoples. AIPP Printing Press, pp.51-64; Trakansuphakon, P. 2015. ‘Changing Strategies of Shifting Cultivators – to match a changing climate’, in Cairns, M. (ed.) Shifting cultivation and environmental change: indigenous people, agriculture and forest conservation. London, New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis, pp.335-356.

[2] Lave, J . & Wenger, E. 1991. Situated learning. Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

[3] Mischung, R. 2003. ‘When it is better to sing than to speak: the use of traditional verses (hta) in tense social situations’, in Delang, C.O. (ed.) Living at the Edge of Thai Society: The Karen in the Highlands of Northern Thailand. London: Routledge, pp.130-149, see pp.134-135.