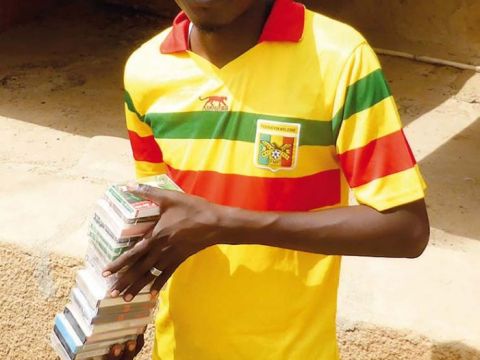

Bouba, the head herdsman and my informant since 2008 for all kinds of stories about herding, the many names of cow hide patterns, names of diseases and remedies.

Languages on the edge: from private archive to shared library

Within the framework of the IIAS programme Humanities across Borders: Asia and Africa in the World (HaB), Mali is the site of investigation for language and translation practices with a special focus on opening and connecting ‘marginal libraries’, that is: the often modest collections of print, sound and film records that any individual or institution might possess. In this regard, both the archives of the host institution, Mali’s Institute of Humanities (ISH), and personal files come into play.

Rethinking the library

The ISH, a descendant of the Institut Français d’Afrique Noire (IFAN), founded in 1936, holds a rich repository of written documents, but also voice and film recordings from the colonial era onwards. The material is strong in history and social anthropology as well as in oral tradition recorded in different linguistic and cultural regions. Of the three research departments at ISH, the Department of Linguistics and Oral Literature was established with the mission to coordinate and harmonize research on local knowledge and the medium in which it is transmitted, preserved, and transformed. Still, the process has been neither systematic nor sustained. Moreover, frequent moves have forced the ISH Direction to stow away a significant part of its documents. The ISH relocated to a permanent site in 2017, and the three departments are only now recovering their archives. With regard to the language archives, though the inventory of the scattered documents started before HaB, its completion and integration into a larger curriculum of training, knowledge production and dissemination has been accelerated through our exchanges around the activities to be undertaken for the language and translation theme of the HaB program.

The next phase in the program is the training of students to digitize priority content and make it accessible to the research community. Part of the planning was done during my visit to the ISH in September 2017. I had brought along samples of private archives, some thirty years old, others quite recent, that I had been sorting out for digitization, transcription and translation. As it turned out, the physical presence of both the material and the portable equipment I had brought stimulated a productive discussion on the best way to move ahead, even if step by step and with limited resources. For that matter, the ISH and similar institutions have recently seen their research budgets drastically reduced or cancelled altogether. The drying up of research funding is officially blamed on increased spending on military and security efforts, but the humanities have in fact always been making do with scarce resources. For the ISH department in charge of revitalizing language research, these sudden cuts have made planning even more difficult, at a crucial juncture. Therefore, HaB has become an even more important platform to share experiences, especially with regard to enabling the co-production of new knowledge and teaching methods. To some extent, the institute’s hidden repository, just like my personal notebooks and tapes, belong to the category of private archives, shrouded in the intimacy of the inner circle, waiting to be part of a shared library that could be open up to fresh and potentially critical perspectives on memories and representations of the past.

Floating family trees

Growing up in a farming village, I first experienced the seasons as alternating cycles of seemingly endless activity with short moments of rest. Of the latter, the end of the rice harvest season remains the most memorable, when, at the peak of the flood season, people traveled by pirogue to visit their relatives along the river. During this period, our house would fill up with visitors, who sometimes arrived from far away. I used to listen to my father reciting names after names, sometimes being interrupted with questions about a person or prompted for details about how this one was related to that one. My father also eagerly told us children about these kinship relations, but I did not have the attention span of his adult guests, often distant relatives, who listened closely to his accounts, engrossed in the intricate details of lineage spread over hundreds of kilometers, crisscrossing today's national territory, even spilling across national borders. Nonetheless, I became aware early of the power of being able to retain such knowledge of ancestry: the capacity to memorize so many names of persons and places, to recall historical events associated with individuals, families and communities, the narrative skills needed to pass on the stories in a precise and even entertaining manner.

A need of narrative structure

My own fascination for the art and technique of such storytelling came later though. Indeed, it took me years of living away from my home region and my family to gain a genuine interest in the stories with which I grew up. The first moment came in my third year at the teachers college in Bamako, 1200 km southwest of Gao. After coming across Charles Bird's research on the hunters' musical and narrative traditions in southern Mali, I decided to write my undergraduate thesis on traditional storytelling techniques, focusing on the prosody of Songhay genealogical and historical accounts.

Initially, I recalled a scene I had witnessed ten years before. In 1977, when I spent part of my school holidays with my relatives in the old city of Gao, we used to attend the evening gatherings on the public square in our neighborhood. Amidst the large crowds of people, several storytellers took center stage, taking turn recounting different episodes of the history of the city and the region. The physical scene fascinated me more than the mainstay of Songhay history about which I had already heard or read in fragments at home and school.

For my college project, I decided to find a master storyteller who not only knew the intricacies of the past, but could also recount them in a compelling way. My search led me to a renowned oral historian in the old city of Gao, whom I recorded over one afternoon. I returned home with the tape, which I played before my father. He turned out to be both an engaged and skeptical listener, asking me several times to replay statements, commenting on what he found accurate, dubious, or far-fetched. I realized that in recounting the past the deeds of well-known historical figures were the most subject to discrepancies and controversy. My father's objections to some detail or other had a lot to do with how he identified with a given character in the story. The other's account, at times, either displaced the centrality of our own lineage in the context of local history, or produced portraits that did not correspond to the image my father had of these ancestors. I came to the conclusion that there was no single story to be told and that an important task in my project could be to tease out the elements of empathy and self-identification, and, conversely, aversion and rejection that might drive the storytelling and shape the relationship between the narrator and the topic, object or figure of narration.

This questioning also led me, in the second phase of my project, to record my own father so that I could listen to him in a different context – detached, to some extent, from the immediate moment or familial context. Therefore, I returned to Bamako with the two narratives, one based on a linear account of the shared history that most people knew and shared in different forms and lengths, the other of a more personal and subjective nature as it started with and revolved around the origins of one family.

In the end, I changed my thesis topic altogether, yet I kept the tapes close to me and even brought them along as I attended a summer school in creative writing in the United States in 1987. There was a week-long workshop dedicated to storytelling in Elkins, West Virginia, but aside from discovering different and lively traditions of declamation, especially from the Appalachian region, the course didn’t yield any practical use for my tapes. I was bound to carry them along to the different places where I would live between 1987 and 1999. They followed me to Niger for a year and to the American Midwest for ten years. For the most part, they ceased to be present in my consciousness.

Renewed sense of urgency

When I rediscovered them again in full, ten years later, the recording of the oral historian was intact. It struck me then as the performance of a well-trained, routine performer. The speaker came across as a warm conversation partner, who, at times, provoked the listener or replied ironically to a wrong answer to one of his rhetorical questions. In all, he was an agile performer who enjoyed sharing his knowledge and establishing his authority as the master of the word.

On the other hand, my father spoke in a neutral, metallic voice with hardly any interruptions, until the tape started to waver and die altogether after thirty-two minutes. The rest of the tape was hardly audible. It came to an abrupt end, just when he was telling me about the situation in our village near Gao at the onset of the French colonial era. I seemed to have never truly grasped the content of the story, as before I had only focused on the form and style (prosody) of the story. I had been interested in the strategies used to memorize such complex details, to keep a narrative going with hundreds of names, events and places, spanning different centuries and epochs. The brutal interruption in the story, when my father reflected on the fundamental shift that had occurred in local governance and the nature of social bonds, motivated me to make up for the lost recordings. There were other points I had hardly noticed, and one unfulfilled promise still lingers with me. He had asked me to go see an ailing, elderly woman in our extended family in the old city of Gao, and ask her for more precise details about my mother's side of the family, considered to be more deeply rooted in the area and related to key figures of the past.

To be sure, as I started my seventh year in the Midwest, listening to the distant voices of my father and his contemporary prompted in me a sense of urgency that I had never felt before in relation to the long, fragmented and variegated story of the Songhay-speaking people and their heartland between Djenné and Niamey: the cycles of being a dominating power and a cluster of subjugated dominions; the dramatic end of their empire with the Moroccan invasion in 1591: the collapse of the last major regional state, which marked the irreversible shift of power from the Saharan desert routes to the Atlantic ocean lines; the rise of imperial and colonial Europe; the transatlantic slave trade to settle and exploit the Americas with free African labor, which fed the industrialization of the West and prepared for the colonial era, which the African continent has yet to exit.

In 1997, as I delved into slave narratives for my dissertation on the discourse on the African diaspora, it became clear to me that, one day, the oral fragments I had recorded could help substantiate part of a narrative that could neither be linear not complete. Like American slave narratives, the stories of the West African past are permeated by traces of displacement, bondage, yearning for freedom, and the destruction and reconstruction of a homeland. Nevertheless, they also convey a sense of wholeness and rootedness that is hard to associate with the transatlantic experience of radical disruption. I decided to have my younger brother do a follow-up recording with our father. The 1997 recordings would last 320 minutes. I was not present at these sessions, but this made me all the more the narratee. Distance pulled me into the center of the story as my name was uttered every time my father decided to tell the genealogy from my generation to the most distant ancestor recorded in our lineage on his side and my mother's.

Transcription: listening (more) closely to silence

More recently, transcribing the 1987 and 1997 recordings has enabled me to listen more carefully and make more direct comparisons between the narrative threads and specific details, including the scores of names repeated as the genealogy was recited in a concentric way: from the family to the village, from one village to the next, among related villages, and across whole regions. This way, we learned how, on his father's side over three centuries ago, people left the Massina (Macina), 630 km to the south, migrated in stages northwards and settled in places in today's regions of Mopti and Timbuktu before finally reaching Gao.

Dealing with the recordings has never been an easy task for me. On the one hand, they are intimate, private stories about the interwoven strands that constitute our family heritage. On the other hand, they also represent a shared story, as they retrace the lineage of thousands of people from the Mali-Niger border to the central region of Mali. From east to west, they cover at least 900 km and uncover the multi-ethnic roots of families like mine. For instance, my ancestors who left the Massina were Fulani. They went north and east, mingled with the Songhay, Tuareg and other populations they encountered along the way; yet, I declare my ethnic and linguistic identity today as Songhay. To be sure, even in my childhood, people occasionally referred to us as Fulani, because ’technically’, our paternal side can be traced back to a faraway Fulani heartland, although my mother's family is considered to be part of the indigenous Songhay stock of Gao. In fact, for a long time, my own representation of the recordings revolved around the genealogy, the part that connected me to my parents and made me part of a web of kinship, and especially my relation to people who today identify with a specific ethnic group, with its associated language, social culture, and worldview.

However, as I resume working with the recordings, I realize that in my representation of the material, the share of the genealogical part is in fact exaggerated. While it makes up about half of the audible part of the 1987 recording (16 out of 30 minutes), it ends after 25 minutes of the 320 minutes recorded in 1997. Given the overlaps in the rendering of family trees, the genealogical component is just about 30 minutes. The remaining 320 minutes cover other topics; recently, these have become more relevant, motivating my effort to transcribe and translate the material in full.

From genealogy to general history

The genealogist is the guardian of collective memories. Starting with the family unit, he or she weaves together the complex fabric of kinship, made of unions and separations, harmony and discord, old and new identities. In this regard, beyond reciting a lineage, genealogy links persons through time and space. Genealogical knowledge used to be considered an important strategic knowledge base; this is why people travelled from far away to consult the expert, able to disentangle the intricacies of a particular ancestry. This is what brought people to my father. From his parents, he had learned the lesser known history of the Fulani migration from central to northern Mali, which would have a sequel at the end of the 19th century with the last waves leaving Gao for the Sudan between 1898 and World War I, prompted by drought, famine and the bloody suppression of revolts by the French colonial administration. The resulting colonies still populate at least six villages in today's Sudan and largely speak Songhay. However, recent emigrations to the Gulf States are once again shifting the cultural and linguistic identity of these ‘enclaves’. By all indications, the youngest generation tends to be more fluent in Arabic and English and again identify as Fulani as there is a more continuous presence of this ethnic group across the Sahel, from Senegal to Cameroon.

Poetics of everyday life

Having transcribed and partially translated the recordings, I am now focusing on the interstices of different narratives, recorded about familial and regional histories over the last three decades. The centrality of the Songhay empire in West African history and its global relevance are well known, thanks to the chronicles and testimonials written by traveling scholars of the Arab-Islamic world as well as local chroniclers in Djenné, Timbuktu, Gao and Essuk, from the late Middle Ages to the colonial era and throughout the 20th century.

More recent narratives help us supplement fragmentary and inaccessible documentation, especially by shedding light on the practice of everyday life, giving insights into material culture, social layers and classes, ethical and moral standards, prejudices and biases, affect or interpersonal proximity and distance. Thus, at the current juncture, I find of more interest the inner dynamics of my father's family and its relation to the larger community: the social status of my grandfather as a single child; the early death of my father's parents and the adoption of my father and his siblings by a childless aunt and her husband; his coming of age under the regime of forced labor imposed by the French colonial power; the cycles of bounty and famine; abundant and erratic rainfall that culminated in the historic drought of 1973-74, which would have an irreversible impact on Gao and the Sahel and shape the landscape of desolation and disorder that nowadays figures at the center of global strategic concerns, including rural emigration, endless wars, displacement, trafficking of all kinds, militant jihadism and nihilistic terrorism. The narration of ordinary life gives us such a direct and lively access to the past, rendered in voices that spoke a language, which, in the meantime, strikes by its intellectual precision and lyric power.

Interestingly, even before joining the HaB platform, research at the Institute of Humanities has increasingly focused on studying social dynamics in highly localized contexts, for example: how gender relations evolved over time in a village or restricted area; how traditional chieftaincy emerged or disappeared in one place when moral or religious authority merged with political power in another; how iron or another metal, as craft or merchandise, fashioned relationships between regions. Such questioning can be extended to all the themes as pertaining to the different HaB sites in West Africa: the memory of interregional migration in the construction of a grassroots West African identity (Ghana); the role of indigo cultivation and dyeing in keeping endogamous communities linguistically unified and economically sustainable from the 17th to 21st century (Burkina Faso); the place of street food in reshaping popular culinary art and municipal policy in steering the production and consumption of foodstuff in modern African cities (Senegal). In all these areas, there is a strong need to interrogate local memories and contexts to get a more accurate picture than the generic representations still predominant in African studies. Moreover, the HaB framework challenges specialists and practitioners to reflect on both African and Asian contexts to tease out both commonalities and particularities.