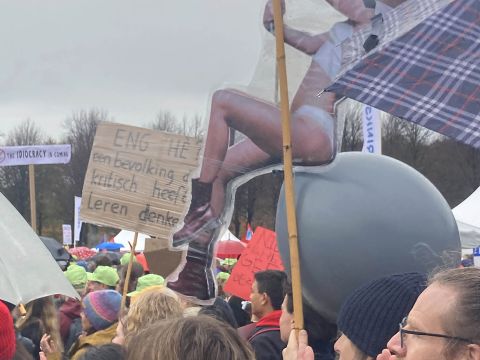

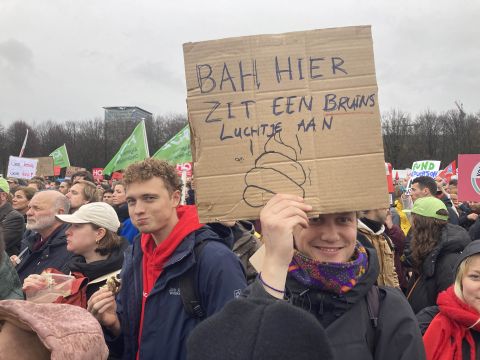

A follower of Dutch politics will recognize the image of the little devil with the bleached haircut as Geert Wilders, leader of the largest far-right party PVV and winner of the elections. Photo: TV

DOE HET NIET! (DON’T DO IT!)

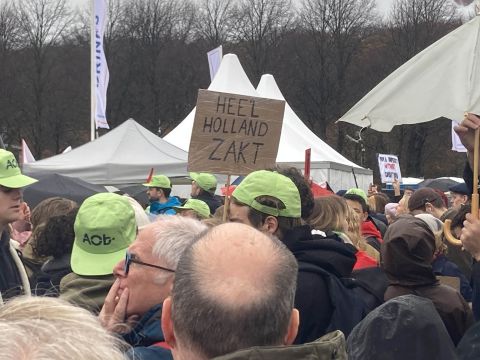

On 25 November 2024, more than twenty-five thousand students, teachers, researchers, and staff members of Dutch universities and polytechnics are gathering on a large, muddy field in the middle of the city of The Hague. The air is filled with outrage, anger and disbelief. People are chanting out loud: “Doe het niet!” (Don’t do it!) Why is everybody so upset? What’s going on?

In November 2023 the general elections in the Netherlands – like in other European countries - saw a victory for conservative and populist right-wing political parties. The government coalition which resulted from this election, announced in October 2024 budget cuts in (higher) education and research & development of almost 2 billion Euro annually!

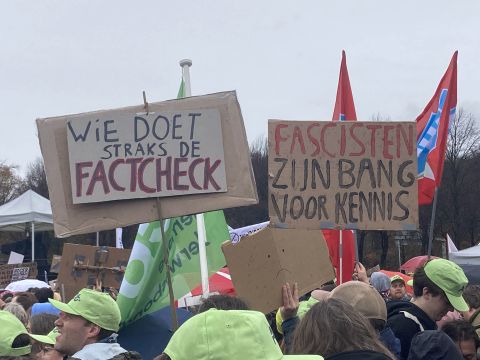

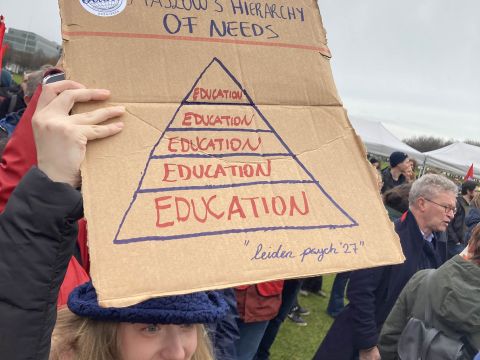

Like their far-right colleagues in other European countries, members of the largest coalition party, the Freedom Party (PVV) view universities and other higher education institutes as left-wing strongholds where “woke” ideology reigns supreme. The announced cuts were presented to the public as a response to "activist woke culture" and as a means of putting pressure on universities to adjust their core priorities. During a parliamentary debate in June 2024, PVV representative Reinder Blaauw made the party's position unambiguous: “For too long, the activist woke culture has dominated the lecture halls and educational institutions. And too often, political activism has come before scientific integrity. Fortunately, that time is over.” However, what's being labeled as a crusade against "wokeness" appears to be something far more concerning: a wave of anti-intellectualism that threatens the foundation of Dutch education. The proposed budget cuts aren't just numbers on a spreadsheet – they represent a direct challenge to the Netherlands' academic standing and its future as a knowledge economy. By targeting universities under the guise of ideological reform, these measures risk undermining the very institutions that drive innovation, critical thinking, and economic progress in Dutch society.

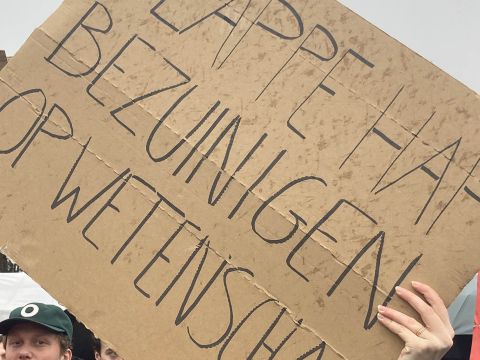

The proposed budget cuts package initially contained, among other things, a slow student fine, restrictions on internationalization and international cooperation, a freeze on new research projects and funding, and significant reductions in academic positions. Student associations, education unions, university boards, and civil society groups mobilized to organize protests. An initial demonstration planned for November 14 in Utrecht was canceled when the city's mayor cited safety concerns after pro-Palestine groups announced their intention to join. Alternative demonstrations, sit-ins and walk-outs were organized across the Netherlands instead. A new day of national protest was announced for the 25th of November in the Hague, the seat of Dutch government.

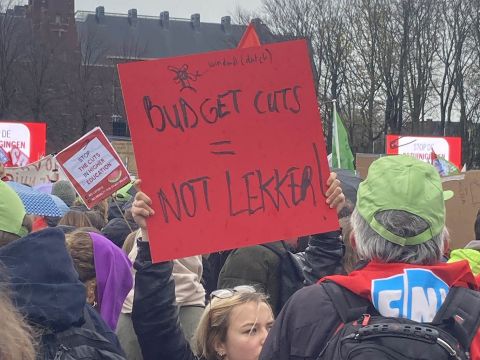

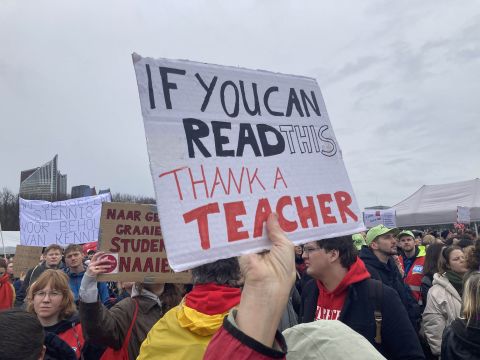

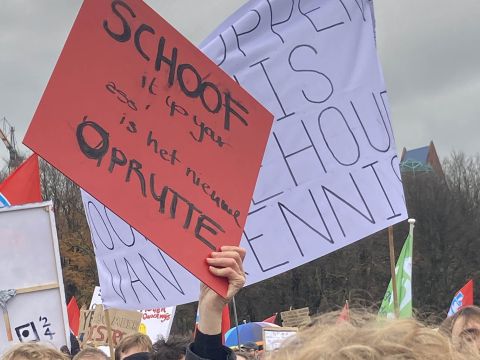

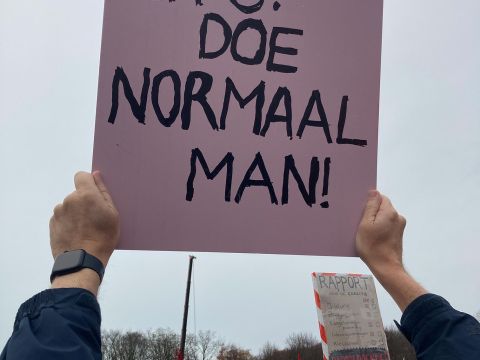

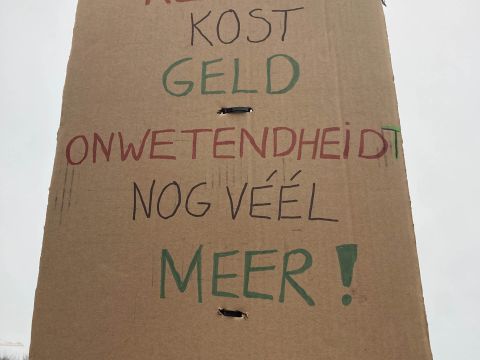

I joined the protest that day with ten colleagues from the International Institute for Asian Studies. Trains and busses to The Hague were packed, the weather was cold and drizzly, but the mood of the protesters hot and steamy. We listened to the speeches of union leaders and politicians (opposition parties categorically reject any cutbacks on education and innovation, as do many other civil society organizations and businesses) and are shouting in unison “Don’t do it!” and “Stop the Eppocalypse!” – a pun on the name of Eppo Bruins, the Minister of Education, Culture and Science. Many creative protest signs were held up in the air and red squares – the global symbol of resistance against budget cuts – adorning clothing and surfaces everywhere.

Although the (agro-)populist and far-right government parties now have the majority in the House of Representatives (Tweede Kamer), they lack control of the Senate (Eerste Kamer), where legislative proposals are approved or rejected. Without support from opposition parties in the Senate, the proposed budget cuts cannot be enacted. Just before the end of 2024, a deal was struck with four centrist and conservative opposition parties, who agreed to reduce the initially proposed 2 billion Euro annual cuts by 748 million Euro, still leaving a substantial 1.2 billion Euro in annual cuts to be implemented.

The long-term study fine is now off the table, but still 90% of the proposed cuts to scientific research remain intact. This does not mean an end to protests and resistance against the brute demolition of our knowledge infrastructures. Relay strikes have been announced in March. It’s going to be a hot spring this year for Dutch academia.

News sources

HOP (2024). 'PVV ziet bezuinigingen als wapen tegen ‘woke’', Ad Valvas, 11 June. Available at: https://advalvas.vu.nl/wetenschap-onderwijs/pvv-ziet-bezuinigingen-als-wapen-tegen-woke/

Kammer, C. and De Haan, M. (2024) ''Monsterverbond' staat niet te juichen bij eigen akkoord over onderwijsbegroting', NRC, 12 December. Available at: https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2024/12/12/monsterverbond-staat-niet-te-juichen-bij-eigen-akkoord-ovre-onderwijsbegroting-a4876539

Kersten, A. (2024) 'AOb: politieke deal over bezuinigingen onacceptabel, voorbereiden op staking', AOb, 12 December. Available at: https://www.aob.nl/actueel/artikelen/aob-politieke-deal-over-bezuinigingen-onacceptabel-voorbereiden-op-staking/

HOP (2024). 'Veel woede om dekking onderwijsdeal', DUB, 19 December. Available at: https://dub.uu.nl/nl/nieuws/veel-woede-om-dekking-onderwijsdeal

Kersten, A. (2025) 'Hoe rechtmatig zijn de bezuinigingen op het hoger onderwijs, wil de Eerste Kamer weten', AOb, 19 February. Available at: https://www.aob.nl/actueel/artikelen/hoe-rechtmatig-zijn-de-onderwijsbezuinigingen-wil-de-eerste-kamer-weten/