Cloth is a woman (seeker)

Two companion vakhs or ‘utterances’ (# 38 & 39) of the 14th century woman poet-mystic Lalla or Lal Ded, translated from the Kashmiri by Ranjit Hoskote.

A total of 258 vākhs attributed to Lalla have circulated widely and continuously in Kashmiri popular culture from the mid-14th century to the present in the form of songs, proverbs and prayers and are testimony to an ongoing process of linguistic and cultural syncretism. Lal Děd has been venerated both by Hindus and Muslims for nearly seven centuries. But from the late 1980’s it has become a conflict region, with the expulsion of the Hindu minority in the early 1990’s and the erosion of Kashmir’s unique, plural, and syncretic culture.

Lal Děd was Lalleśvarī or Lalla Yogini to the Hindus and Lal-‘ārifa to the Muslims. Hoskote laments that “…today, unfortunately, these descriptions are increasingly being promoted at the expense of one another. He therefore prefers to use her most celebrated and nonsectarian appellation, ‘Lal Děd’ meaning ‘Grandmother Lal’; more literally, it means ‘Lal the Womb’, a designation that connects her to the mother goddesses whose cults of fecundity and abundance form the deep substratum of Indic religious life.” Another name by which she is known affectionately, across community lines is Lalla. Sixteen of the 146 poems in Hoskote’s book bear the signature line bear ‘Lal bǒh’, meaning ‘I, Lalla’. Unlike signature lines employed by male poet saints between the 15th and 17th centuries (Kabir and Tukaram for instance signed off as ‘says Kabira and ‘says Tuka’) these signature lines, according to Hoskote, are “a prelude to action, the assertion of a particular self through performance.

This rendition of the biography of a cloth in the utterances of Lal Ded to me speaks of life’s arduous journey to self-knowing. Given that she writes in a context of religious heterodoxy (against scriptures, priests, ascetics and rituals and prayers of orthodox Hinduism), what strikes me in these two companion vakhs is the poet-mystic’s ability to transpose. She uses the artisanal making of a cotton garment – something from the everyday life and labour of people around her – as a performative metaphor of her own spiritual quest. The description of the different processes of carding, weaving and cutting are visceral and refer to the arduousness of the process as if she herself was being fashioned into ‘becoming’ – from the inside out - like the transformation of a seed into a mature fruit, via the masterful skill and labour of different social actors – the cleaner, the carder, the spinning woman, the weaver, the washerman and the tailor – even if brutally. If cloth is a woman seeker, then she must be shredded, torn, twisted, spun, hung, beaten, woven, pounded, washed and cut to measure. One is immediately drawn to the materiality and body-centric imagery … which in Hoskote’s words is as though “…her sense of personality, must be beaten out of her.”

It is very interesting that the interdependence of the occupational groups, are catalysts harmoniously working together in the quest of the cloth/seeker. In many ways, I see these artisans subverting the prevailing caste and ritual hierarchy through a more materially grounded spiritual underground!

The word vākh, applicable both as singular and plural, is cognate with the Sanskrit vāc, ‘speech’, and vākya, ‘sentence’. This has prompted previous translators to render it as ‘saying’, ‘verse’ and ‘verse-teaching’; Hoskote prefers to translate it as ‘utterance’.

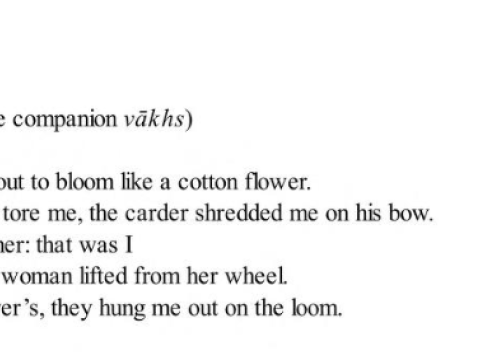

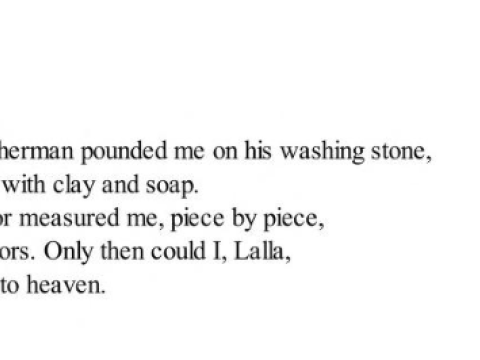

Lal bǒh drāyěs kapasi-pōshěcě sütsüy (38)

dǒbi yěli chövünas dǒbi-kañě-pěṭhạy (39)

For translation see Media Asset – Text at left.

Original vakhs or ‘utterances’ (# 38 & 39) are attributed to woman poet-mystic Lalla or Lal Ded

Translation: The Kashmiri by Ranjit Hoskote, Penguin, 2011. (https://archive.org/details/ilallathepoemsoflalded/page/n83/mode/2up)

Jammu and Kashmir

India