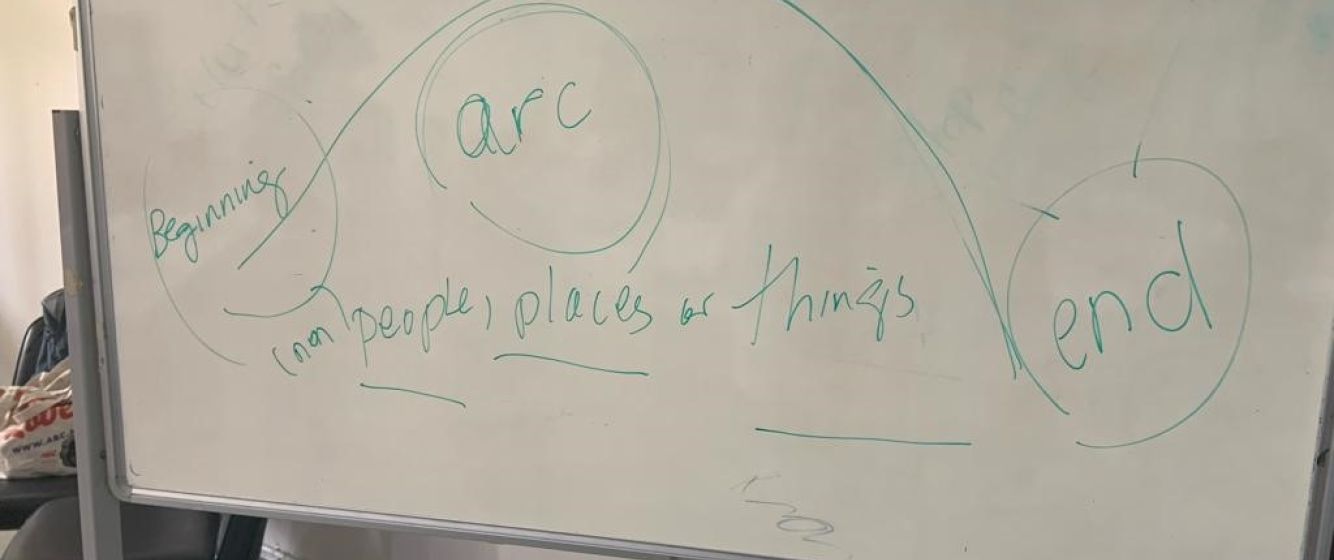

A visual drawing of a story arc from Day 1. The structure of a story arc (beginning, middle, end) acted as guide for the trainees during the workshop when developing a story covering (non)people, place and things. Credit: Jyothi Thrivikraman (2023)

Sharing Stories That Matter: Reflecting on Myanmar Underground Educators

As part of November's "Community Storytelling and Place-based Education: Learning with Memory" educational workshop in Chiang Mai for Burmese underground teachers, facilitators Jyothi Thrivikraman, Surajit Sarkar, and Yi Li reflect on their experiences in teaching with their Burmese students, the challenges in adapting to a language barrier, and how an atmosphere of understanding & normalcy led to stories about hurt and trauma, and their importance in being heard.

First brought to the attention of HAB researchers by Tharaphi Than from Northern Illinois University (NIU) in the 2022 'Craft as Method' workshop, she and the other major facilitators of the workshop (Jyothi Thrivikraman of Leiden University College (LUC), Delhi oral historian Surajit Sarkar, and Yi Li of Aberyswyth University Wales), would go on to design course materials and hold practice workshops, such as June 2023's 'Underground Educators of Myanmar and What We Can Learn From Them' workshop in Leiden, in preparation for this event. Since the 2021 Myanmar military coup, there has been an educational crisis in the region, with the military junta-sponsored education actively marginalizing and oppressing the voices of the local populations. Emergency education provided by the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) has provided an alternative, with the goal of this workshop being to encourage alternative learning methods through storytelling, using the stories of the students to create learning teaching materials that incorporate these marginalized voices, and preserve memories independent from the state educational system.

Heading into the workshop, the goal was to show the participants the power of place-based education and how storytelling can provide a personal connection to their students, and acted as learning experience for the facilitators themselves. For some, like Tharaphi and Yi Li, there was some familiarity with the context of their trainees prior to this project , but for others like Surajit and Jyothi, it was the chance to learn about what life was like for these underground educators first-hand.

The feeling that stood out at the onset of the workshop was a sense of normalcy. Many of the trainees would point out to the facilitators how this was the first sense of it they have had in a while, and how seemingly normal things would elicit different reactions from them. The traumas they have felt since the coup weighed heavy on them. Surajit mentions a short anecdote about his arrival in Chiang Mai:

I was lucky to arrive early and spent time with a three participants and local organisers. At one point, when there was an active conversation in Burmese, there were some words which I could follow. Inquiring, it emerged that for one, it was his first day at Chiang Mai, and the way sounds of planes and fireworks (a festival in CM then) made him fearful, before he realised he was in a different setting. The psychological impact of violence and displacement and made me realise this workshop would be different. - Surajit Sarkar

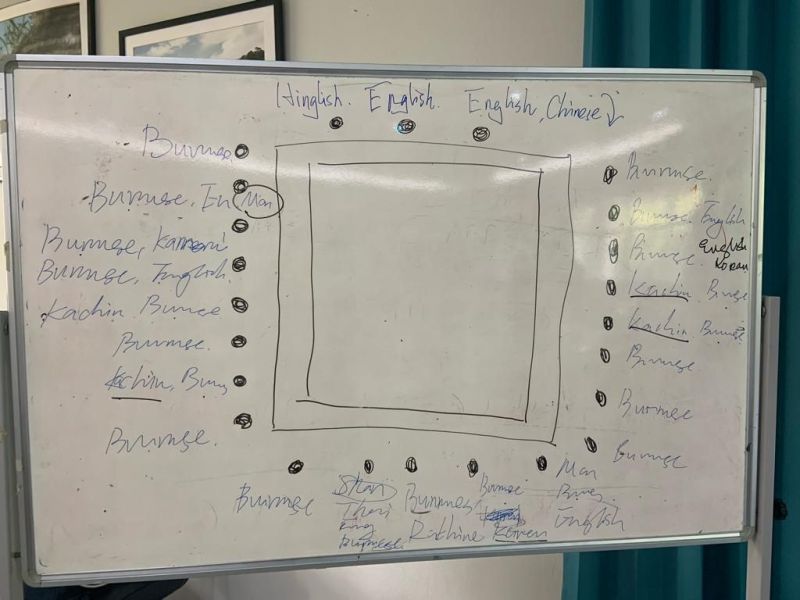

Language loomed over the workshop throughout as a potential challenge. Tharaphi, the one most familiar with Burmese and the other regional dialects of Myanmar, was unable to attend the workshop. This led to the rest of the facilitators to adapt and work with the students despite the language barrier, often using digital translations to communicate. This led to certain voices becoming more prominent than others, highlighting a language hierarchy that often comes up in academic research, with English at the top and regional dialects being less emphasized.

While we did the best we could, the voices that spoke were those able to navigate English more easily. Even in small group sessions, some voices were still more prominent. - Jyothi Thrivikraman

A whiteboard from the first day of the workshop, highlighting the various languages that the facilitators and participants felt most comfortable speaking in.

Jyothi Thrivikraman (2023)

In addition, the workshop’s original program was very structured and rigid, with specific activities and time frames already planned out beforehand. However, after the first day’s activities, they received feedback from the students that this approach to teaching, aptly referred to as the ‘western’ style of teaching by Yi Li, would not work for them.

One thing I noticed is the different pace of 'teaching and learning' between this workshop and the usual classrooms in my university in Britain. Although I myself started my education in Asia, I think after decades as a student and now a lecturer in the UK, I am now used to the 'western' style of learning of teaching, i.e. everything is planned well in advance, every action must have a purpose, and every minute must be utilised fully. In Chiangmai, our on-spot feedback often told us the students were not getting into this fast and precise rhythm, no matter how smart and dedicated they were. - Yi Li

Because of these issues, the facilitators chose to adapt to the needs to the students, shifting the schedules and giving more time for the trainees to ruminate and process their interactions. In addition, they would receive regular feedback through the course of the workshop, allowing for more responsive experience.

We realised early on that the participants needed time. Time to do the activities, time to sit in the content. This is relevant not only for this workshop, but I would argue teaching in general. We want to move from concept to concept and measure learning outcomes, but students need time to absorb the information and incorporate it into their daily practice. Slowing down is critical in any teaching/learning situation. Slowing down is critical to change the focus away from endless push to think about growth or the next big thing. - Jyothi Thrivikraman

What was never in doubt however was the passion of the trainees, which shown through the different stories they shared about their lives, as well as in how they viewed the experiences they were having as part of the workshop in the relative security of Chiang Mai. Activities included storyboarding exercises based on site visits around Chiang Mai, as well as the sharing and recording the stories of personal objects brought with them from Myanmar.

Trainees making a storyboard of their visit to Payap University in Chiang Mai during Day 3 of the workshop. They were tasked with making note of the different things that struck out with them and how they visualised it, then used the images to tell a story.

On the final day of the workshop, the facilitators stepped back and allowed the participants to run the discussion entirely in Burmese, to allow for as many voices to be heard as possible. While this made it difficult for the facilitators to intervene, in the end it was not necessary, as it handed the space over to the participants. This empowered them and gave them the validation to share their stories, many of which were traumatic and filled with regrets and “what ifs”.

Across the group, diverse in age, gender, ethnicity and language, their varied experiences of trauma was clearly an important barrier they would need to overcome if they were to transform their experiences into stories. How could stories of hurt, suffering even death need to be told? Did they matter? A discussion of the validity of such stories and the importance of telling them was a discussion that was led by the participants, while us facilitators tried to reassure them that this discussion was also important, that ‘our stories matter’. - Surajit Sarkar

And their stories do matter. In conducting this workshop, not only did the trainees learn first-hand how sharing and recording personal stories can help a student connect with their learning materials, but also reminded the facilitators about the human element in education. Stories like this help people empathize and connect through our similarities, but also highlight what makes local communities unique in their own way. By understanding and adjusting to those differences pedagogically, that is one of the ways we can address the question of decolonizing education.

To read more about the Learning with Memory educational workshop, see the event post for the program, and our upcoming article in the 98th issue of the IIAS Newsletter, which goes into detail about the stories of the participants through excerpts from one of the workshop activities.